Kleber Mendonca Filho's Aquarius is an introspective character study of Clara, a 65 year old widow and retired music critic, who lives in Aquarius, a quaint two-story building, located in the upper-class, seaside town in Recife, Brazil. Aquarius has seen better days, being built back in the 1940s, but while all the neighboring apartments have been vacated, Clara remains, wishing to live out her life in the apartment which she was born and raised. With all the neighboring apartments having already been acquired by a business company that has plans for the plot of land, a quiet battle begins to unfold between Clara and the management company, a struggle which triggers Clara to reflect on her life, past and present, as she questions what her immediate future may hold. Kleber Mednonca Filho's Aquarius is an intricate, intelligent study of a strong woman in Clara, a character who has lived a full life from the perspective of many, having both succeeded in a career that saw her tour the world doing something she loved, while also being lucky enough to have raised a family herself, one that has yielded healthy grandchildren which she can be proud of. Aquarius is meditative experience, a film that finds a woman in Clara in a state of reflection, concerned about the future of her home, merely a piece of property sure, but one thats halls are drenched in memories both good and bad from Clara's long, lived life. Aquarius stands out so much as a film due to just how refreshing of a characterization it presents with Clara, an older woman who is strong yet fragile. This feeling of time passing one by is met by a strong-willed character in Clara, with Aquarius fully capable of capturing both elements wonderfully, delivering a potent portrait of an older woman who has not given up on experiencing all of which life has to offer. There is a quiet sense of pressure throughout the film from the younger new generation which makes Aquarius so compelling, whether it be from Diego, the young, head-strong real estate developer, or Clara's own children, some of which encourage her to take the buy-out offer, the film evokes a sense of quiet weight throughout, one of an older generation feeling pressure from the younger generation to conform or get out of the way, so they can have their time in the spotlight. While her siblings and children are a part of Clara's life, much of Aquarius regulates them to the background outside of a few scenes, reminding the viewer how much of Clara's time is spent alone at this stage of her life, where she is alotted so much time for reflection and meditation. While the driving force behind the narrative of Aquarius is focused on her impending battle with the land developers, this chilling threat to her home and memories is regulated more to the background throughout the film, a thorn in Clara's side, which only escalates when the civility between the businessman and Clara is dropped towards the end of the film. The greed of the land developers, led by Diego, a young and hungry businessman, is experienced yet often regulated to the background of the story, always lurking yet never overtaking this powerful and intricate characterization of Clara, a strong, loving woman who is confronted with the weight and uncertainty centered around the notion that she could eventually lose her home. Aquarius is a film that attempts to combat this notion of the older generation being passive with its characterization of Clara, a woman who may be old physically but still young, strong, and proud at heart, willing to fight for her past while she attempts to contemplate her future. Through showcasing Clara's past, all she's been through and the life she has lived, Aquarius touches on why Clara's present is so lively and future is so critical, exhibiting how she has been shaped by past tragedy and so willing to fight for her home and those which she loves. This sense of uncertainty about her future weighs heavily on Clara throughout the film but it never consumes her either, with Filho's interjecting a subtle amount of surrealistic moments into the film in an effort to evoke this character's sense of quiet fear that distracts but never deflects from showcasing a woman in Clara who is very much alive, living a vibrant existence even in her later years. Filho's direction as a whole is potent but nuanced throughout, a filmmaker whose visual design is meticulous in execution, using an array of assured camera movements, whether slow pans or zooms, to draw the viewer's attention to the specific details of a sequence. Featuring a narrative centered around an older character in a state of reflection, Kleber Mendonca Filho's Aquarius is a potent portrait about life itself, showcasing a woman in Clara whose past itself has made her present so lively and her future so vital.

0 Comments

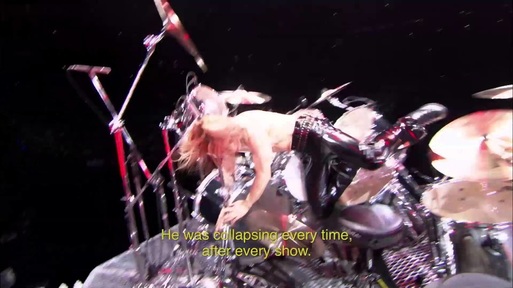

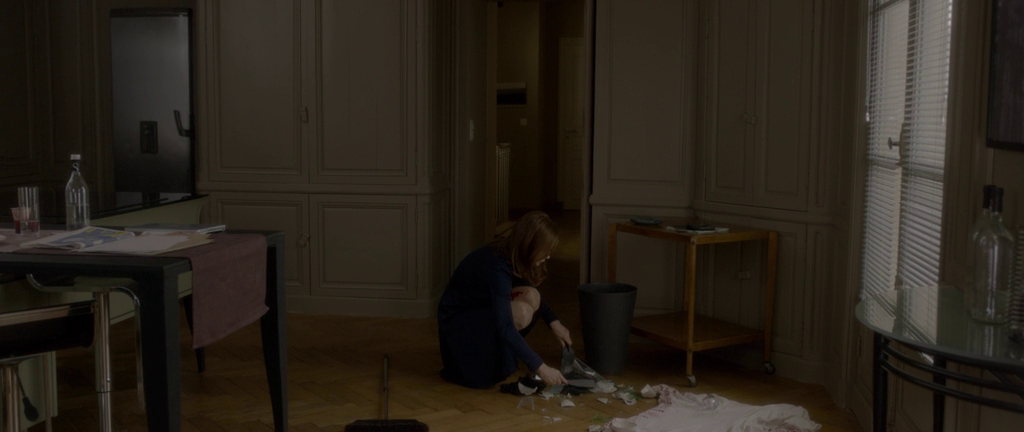

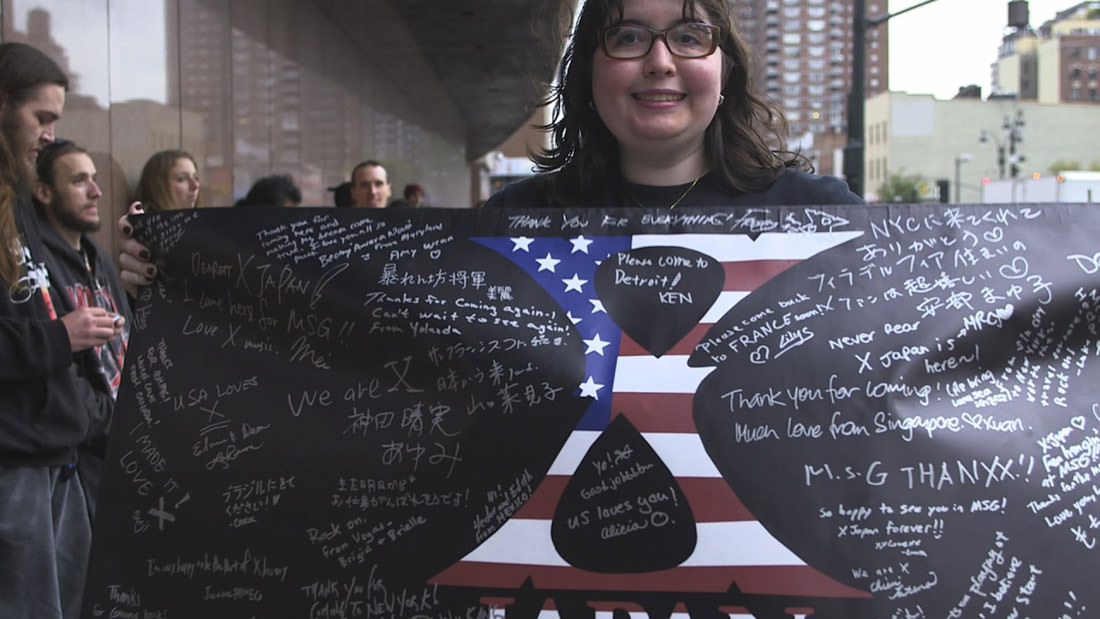

Provocative, risky, and darkly intriguing, Paul Verhoeven's Elle is a story of power, fragility, and control detailing the life of Michele, a successful businesswoman, who brings her cold and calculating demeanor to everything she inhabits. Whether it be her video game company or her personal life, Elle is ruthless in her convictions, often alienating friends and family, including her own mother and son, due to her assured perspective on everything around her. Sexually assaulted in her home by an unknown assailant in the opening scene of the film, Elle is not your typical rape/revenge thriller, as Paul Verhoeven has crafted a film willing to take taboo risks, as it attempts to deconstruct the fine line which exists in the psyche of Elle between pain and pleasure, sex, violence, and control. A slowly unraveling character study of a woman whose inner turmoil and confusion stems from a deeply troubling past, Elle is a film about loneliness, insecurity, and control, or lack-there-of, with Isabelle Huppert's performance bringing a quiet fragility to this character who essentially routinely wishes to pretend that she still has complete control over her emotions and those important to her in her life. Elle is a headstrong character who is trying to her best to be someone she is not, overreaching in her desire to be tough and strong due a sorted past. She is a character still plagued by the heinous acts of her father, a serial killer, with Verehoven's film slowly revealing a woman whose quiet sense of loneliness rings louder and more true than any of Elle's power-posturing throughout the film. The cat and mouse game which ensues between Elle and her assaulter is both curious and thrilling to this character who is so used to being in control, as the lines between sex and violence, pain and pleasure become further blurred in the psyche of Elle, a character who struggles to admit her own weaknesses and imperfections. Elle's need for power and control over those around her, whether it be through sex, finances, or emotions, is shattered by this intruder in the opening scene of the film, with sexual assault being such a heinous act of obtrusive power that it slowly and methodically sets Elle on a path of reflection, unable to comprehend at first that she herself has been an obtrusive force to those around her, including her own son and coworkers, with the assault being a chilling reminder that she does not have a monopoly on control and power, something she convinced herself about in an effort to overcome the pain associated with her father's heinous acts of violence on those around him. A singular character study that is as provocative, bizarre, and intriguing as one would expect from Paul Verhoeven, Elle deconstructs humankind's desire for control and need for power, revealing how both are merely a mirage we manifest in our psyches in an effort to be more assured in our own convictions.  While I'm a major fan of Antonio Campos, having liked his first two features a great deal, I must admit I was very concerned about seeing Christine after experiencing Robert Greene's phenomenal Kate Plays Christine, a documentary also examining the last days of Christine Chubbock, a new reporter in Sarasota, Florida who committed suicide on air in 1974. Alas, the concerns of Campos' Christine being exploitative were quickly eviscerated from my mind as I started to watch, as I was quickly reminded how much of a gift it can be for any cinephile when two great filmmakers tackle the same subject matter in different ways. Much like Christine Chubbock herself, Antonio Campos' Christine is a meticulously constructed character study, a film that features the performance of Rebecca Hall's career, who is able to contrast the strong-minded, career-driven toughness with the fragility Chubbock had, a woman who felt the quiet sting of loneliness due at least in part to her inability to form a personal connection, specifically companionship with someone else. Christine Chubbock's emotions are plastered all over the screen in Campos' film, the loneliness, solitude, pain, and feelings of insignificance combine to create a vivid and haunting deconstruction of depression and self-doubt. A phenomenal characterization that is supremely well acted, the story of Christine is absolutely gut-wrenching from the beginning to its chilling conclusion, focusing much more on tapping into the emotions of a character and how one could go to such drastic conclusions, with social/political commentary centered around guns, the sensationalist media, and discrimination taking a backseat to the individual in Christine, a real life human being who fell so far that she resorted to such a tragic act. Campos' film shows great sympathy for Christine Chubbock, a woman who decided to kill herself on live television, with the whole film being emotionally exhausting and tense from start to finish even though I knew exactly what the end result would be. At the same time, Christine as a film doesn't neglect personal accountability, fairly acknowledging the inherent selfish nature of suicide, showcasing how self-hatred is essentially a self-fulfilling prophecy while simultaneously still acknowledging Chubbock's personal and professional hardships. The final scene of the film is a perfect example of Campos' inability to not tackle such a complex story from a singular angle, with Jean, Christine's closest thing to a friend, returning home to her apartment. Simple enough in execution, Jean in her living room is visually presented in the same context as Christine at her home, one of solitude, alone, as if to suggest loneliness is simply a part of the human condition. Antonio Campos direction is subtle and calculating throughout Christine, showing a pensive eye for where the camera should be at times, effectively building the tension through visual storytelling. When Christine is interacting with other characters, multiple times we find Campos' fixating on Christine no matter who is talking, choosing instead to gaze, exposing the quiet depression and pain Christine has bottled up inside. Meticulous in execution and emotionally exhausting, Antonio Campos' Christine is a powerful character study featuring what will most likely be the best performance of the year, a film that shows respect for its subject, attempting as best as a narrative can to truly understand the nature of such a tragic story of a strong, intelligent woman who falls into darkness.  Light in tone yet dealing with heavy themes centered around love, death, dependency, and connection, Hannes Holm's A Man Called Ove is a cleverly structured character study about Ove, a 59 year-old man whose temperament isn't exactly hospitable. The opening of A Man Called Ove is quick to establish our main protagonist as a person of solitude, ill-tempered with nearly every situation he comes across, enforcing the neighborhood associations rules and regulations with an iron fist. Ove's inner turmoil is projected externally, with his short fuse and how he seems to see everything in a negative light being fueled by his anger towards the death of his wife which we come to learn was 6 months ago. Featuring a biting sense of humor that finds the comedy in some pretty dark situations, A Man Called Ove manages to balance its comedy and drama surprisingly well, with both elements being strong overall in a film that feels like a relatively unique treatment of the themes typical in these types of stories. Usually the comedy hits but the drama feels cheap, yet with A Man Called Ove both work equally, with a large part of that being a bi-product of a in-depth characterization. Featuring flashbacks sequences centered around each of Ove's attempted suicides throughout the film, A Man Called ove takes advantage of the known hypothesis that time slows down when one finds themselves on death's doorstep, exhibiting how this ill-mannered character was shaped by a tragic-filled past Through these flashbacks which span from early childhood to adulthood, Ove is exposed to the audience, being an introverted, passive character whose always relied on the close connection he has with another, whether it be his late father or late wife. A major source of comedy are Ove trying, and failing, to kill himself repeatedly, exhibiting a character who avoids the neighbors until an unexpected friendship with a new resident on the block begins to emerge. Ove struggles to admit he needs others in his life, with film exposing the need for connection in humanity, with having someone to confide in being fundamental to the human experience. In this sense, A Man Called Ove is a profound, tender love story, more about the fundamental nature of what defines love than most films around, doing so with dark humor as its main way of transport. While A Man Called Ove does teeter on the edge of over-sentimentality, specifically towards the end of the film, Hannes Holm's has crafted a cleverly structured narrative that aids in delivering a strong characterization in the form of Ove, an essential attribute that goes a long way in making this film worth seeing.  Seeing acclaimed Japanese filmmaker Kiyoshi Kurosawa return to his horror roots, Creepy is an expertly crafted, tense experience, a film that carefully weaves an atmosphere full of mystery and dread, showing just as much interest in the psychological toll malice has on the human psyche as it does in providing the audience with a thrilling experience. The film is centered around recently retired Takakura, a former police detective, who now works as a Professor of criminal psychology at the local university. Having just moved into a new home, Takakura and his wife, Yasuko, have started anew, leaving their more chaotic life in the big city behind them, where they to find a place they can call home. While Takakura's wife struggles to make friends with the local neighbors, including Nishino, a strange man with a sick wife and young daughter, Takakura receives a request from an ex-colleague to help solve a case of a missing family, one that has gone unsolved for over six years. Takakura can't resist the urge to help unravel the mystery of this unsolved case, but the deeper he gets into the investigation, the more he begins to suspect that his new neighbor, Nishino, may in some way be connected. Kiyoshi Kurosawa's Creepy is a horror film based in reality, fixating the inherent evil and darkness that can exist in humankind. Everything in Creepy feels genuine and possible, with the film's narrative having as much in common with a dark, crime thriller such as David Fincher's Seven, as it does with traditional horror. There are no jump scares, no didactic decisions made for the sake of startling the audience, no wasted scenes simply their to serve the narrative, only a methodical, well-constructed drama that slowly unravels itself to reveal the true evil lurking underneath the surface. The juxtaposition of Takakura's investigation into the missing family with Yasuko's attempts to befriend the off-putting Nishino is intriguing from the very onset, with Creepy essentially telegraphing exactly where it is going, though it doesn't matter, given the skilled direction involved. A phenomenal performance by Teruyuki Kagaawa as the unsettling Nishiro certainly helps, teetering the line between diabolical and socially misunderstood early on, adding a sliver of doubt around what exactly his intentions are, even though the film seems to be leading towards diabolical intentions. Without going into details that could spoil Creepy, Kiyoshi Kurosawa has created a film that wishes to examine the psychological nature of horror, deconstructing the power the mind has over the body, with Nishino being a character who essentially gains power and influence over others due to the slow-burning psychological torture he instills in his victims. The complacent nature of fear is what Kiyoshi Kurosawa's narrative relies on, painting a convincing and introspective look into the psychological nature of violence and horror, showcasing the effect it has on all of us through Takakura's wife, Yasuko, a woman who herself is more susceptible due to her feelings of loneliness as a housewife. One of the main reasons Creepy works so well is Kiyoshi Kurosawa's phenomenal direction, using space and framing to perfection in creating a film that is quiet but assured in its impending sense of dread that comes to encapsulate the entire film. Everything about Kurosawa's direction is nuanced and assertive, full of intricately designed photography that plays with the audience's perceptions, with the space of the frame being their window into this creepy world, one in which Kurosawa himself controls, choosing what the viewer can see and what rests outside of the frame. Whether it's lingering on a particular composition longer than expected, or using slight camera movements to provoke tension in the viewer, Kurosawa's film plays with the viewers psychologically from start to finish, creating a steady, quiet sense of unease that stays with them throughout the films' running time. A film that shows as much interest in character, theme, and narrative, as it does in horror, Kiyoshi Kurosawa's Creepy is a phenomenal and welcome return to the genre, exhibiting a subtle, consistent sense of dread that is bound to stick with the viewer long after the narrative plays out.  Stephen Kijak's We Are X is a music documentary centered around the Japanese rock band X Japan, chronicling their meteoric rise to the top and their tragedy-fueled fall from grace through the eyes of their enigmatic leader, Yoshiki, a man who routinely battles his own demons. Set around Yoshiki and the band as they prepare for a reunion concert in Madison Square Garden, We Are X is a film that should be enjoyed by both fans of X Japan and those with no familiarity with the rock group, managing to be both informative and deeply personal in execution. We Are X's structure does a lot to keep the viewer engaged, featuring non-linear storytelling that is more focused on capturing the heart and soul behind the music first, examining the men who made up this band, the unity they shared with one and other, and what the music itself meant to each them, detailing how it brought them together for their common goals of self expression. While the film certainly captures the magnitude of We Are X, detailing how they challenged conservative Japanese culture and took the country by storm, We Are X is far more compelling in its human moments, detailing the life of Yoshiki, a man who turned to music to find solace in a time when his whole life was in disarray. With Yoshiki, We Are X exhibits a soul who will do anything for his art, confiding in music as his escape from the pain that is everyday life. Yoshiki is a character who battles both physical and emotional demons, a fascinating soul whose life has been riddled with personal tragedy, mainly suicide which took the life of his father and two of his band mates. In large sense, We Are X is a powerful deconstruction of pain, depression, and suicide, providing a surprisingly introspective examination which uses one man's personal journey through life as a powerful testament to the importance of community, connection, and art. The film itself almost feels like a psychological study of art, showcasing not only Yoshiki's attachment too it post the suicidal death of his father, but also the therapeutic nature which music can have all of us, with We Are X's own fan's finding a form of power and resolve in the metal band's music, helping many individuals get through their own personal pain and strife. Not simply explaining the creation of the band but tapping into the essence of why a band such as We Are X came to be, Stephen Kijak's We Are X paints a convincing portrait of X Japan being founded on the basis of personal expression, detailing how Yoshiki and other members of the band used their art to express themselves, whether that be through rejection of the status quo or a means to deal with their own personal pain.  Set in the barren landscapes across Montana, Kelly Reichardt's Certain Women details the lives of a few women living across the state, having no knowledge of each other, but having a shared experience due to the environment which they inhabit. Told in three segments, Certain Women is a tale of intersecting lives, though they never physically meet, yet emotionally share very similar experiences. There is one scene where the two characters share the same space in the office of Laura Wells, a lawyer, and the central protagonist of the first story, but these characters never interact physically, with two characters of the film having a connection in an other way but I wont detail that yet. Laura Wells, a small town lawyer, is dealing with a lot of stress, struggling to control her disgruntled client, a man who is suffering mentally, physically, and emotionally, feeling slighted by a worker's compensation settlement Laura Dern's performance as Wells is subtlety riveting, exhibiting a woman who is beyond frustrated with life, feeling underappreciated as a person,at least in part due to her gender. The second story introduces Gina Lews, a married woman who seems constantly in motion. Michele Williams exhibits a strong woman in Gina, the head of the household who is quietly frazzled due to doubts about her husband, having way too much on her mind, including her teenager daughter, and getting the sandstone for her husband to use in the construction of their new home. Like Laura, she deals with subtle disrespect due to her gender, with her opinions being subtlety ignored in one scene, from and older man who they are asking to purchase sandstone from, who always directs his attention to Laura's husband, regardless of who asks the questions. There is a sense of resentment in this man, who while not vocal or hostile in any way shows disrespect for Laura for no discernible reason outside of misogyny. The other connection between the women of these stories, which I alluded to earlier, is that it turns out that the man Laura is sleeping with in the first segment is the husband of Gina in the second segment. Certain Women presents this fact to the audience but never blatantly states whether or not Gina knows of her husband's actions, but it is very clear that he does have a sense of guilt on how he is betraying a woman who does so much. The last segment of the film focuses on Jamie, a young ranch-hand, clearly looking for some form of feminine connection, having lived her life in a very traditionally masculine setting. She takes an interest in a young teacher, Beth Travis, a woman who herself is out of her element, a law student teaching classes in education law in a small, distant town from her school With an awkward demeanor in social interactions, Jaime is a character who struggles to express herself, a woman uncomfortable in her own skin who desperately wants to communicate her affection to Beth towards the end. Like all of Reichardt's work, Certain Woman is a film bristling with genuine emotion, with nothing ever feeling sentimental for the sake of it, presenting a quietly haunting portrait of small-town America. All three stories are females in male driven cultures, with the quiet desolate setting of Montana serving as the perfect atmosphere, the barren landscapes symbolizing the internal struggle of these characters, each who is missing something in their lives. Nuanced, extremely well-acted, and directed, Kelly Reichardt's Certain Woman is another quietly devastating film from one of the best contemporary American filmmakers working today.  Chan-wool Park's The Handmaiden finds the praised South Korean filmmaker at the height of his powers, delivering a skillfully interwoven narrative which is both bold and intricately constructed, transporting the viewer into a one-of-a-kind tale about sexuality, repression, and empowerment. Taking place during in 1930s Korea, during the Japanese occupation, The Handmaiden tells the story of Sookhee, a young girl, who is hired as the handmaiden to a Japanese heiress, Hideko, a beautiful young woman who lives a secluded life in the countryside with her domineering Uncle. While Sookee's demeanor is one of timid resolve, she has a secret, being recruited by Fujiwara, a swindler who poses as a Japanese count to help him seduce the naive Hideko so they can rob her of her fortune. Chan-wook Park's The Handmaiden is arguably the best narrative film of the year, a expertly constructed film that plays with its audience's perceptions from start to finish. Deceptive in execution, The Handmaiden teases narrative outcomes throughout while it slowly reveals its thematic intentions, sneakily becoming a powerful story of female sexual empowerment and love. This is the type of film that I'd recommend going into knowing as little as possible, so with that being said, I'll try my best in this review to not spoil anything, though it's quite impossible to discuss much of the film's thematic ideals without spoiling earlier aspects of its narrative. For much of its running time, Chan-wook Park presents two characters in Hideko & Sookhee as repressed woman, each struggling in different ways with their current status in life. For Sookhee, she views Hideko as her way out of her rural, low-income upbringing, infatuated by escaping South Korea for a better life. Hideko on the other hand is a character who lives a life of solitude, haunted by her aunt's death and her domineering uncle, a sexual deviant who takes advantage of his niece for his own deranged placed. For much of the narrative both these characters find themselves slaves to the whims of their male oppressors, in the form of both Uncle Kouzuki & Fujiwara, but it's through their shared femininity and eventually love for each other that they break free of their shackles. Chan-wook Park's direction and visual design aids heavily in this story, featuring a heavy dose of tight, closeup compositions, exhibiting a sense of intimacy in the early moments of attraction between the young handmaiden & her suitor, giving the whole film a sexually-charged energy that is both subversive and sexy. In a sense, Chan-Wook Park's The Handmaiden could simply be described as a subversive love story, exhibiting two oppressed woman in Sookee & Hideko, who together find themselves sexually liberated by the whims of their male oppressors, finding their own desires and true emotions for each other through this liberation. Perhaps the last scene of Chan-wook Park's The Handmaiden perfectly encapsulates this ideal, finding the two woman in bed together, using a pair of metal balls as a form of sex toy, a fitting way to wrap up this one-of-a-kind tale of female sexual repression and ultimately empowerment.  Barry Jenkin's Moonlight is a powerful mosaic of self discovery and connection, deconstructing the heinous dogma of homosexuality specifically in the African American community, being both universal and specific in its detailed look at its central character, Chiron, a character who desperately struggles to be comfortable in his own skin. Told in three segments, Moonlight details Chiron from early childhood through adulthood, exhibiting how the environment in which he inhabits, one full of drugs and dead-ends, made it nearly impossible for him to find his own sense of individualism and sexual identity. Moonlight exhibits how masculinity and toughness are not simply accepted but expected by males in this culture, showcasing how sensitivity itself is viewed as a weakness, leaving Chiron deeply confused from a young age about his own identity as an individual. One example of this is when Chiron meets Kevin, another young boy, who seems to be masking his sexual idenitity. Alone on the beach, the two share a moment of intimacy, though immediately after Chiron abruptly apologies to Kevin, a reaction which details how deeply conditioned it is in his psyche to believe homosexual behavior is wrong. Chiron's own mother, a drug addict, resents her own child, expecting him to be tougher and look out for himself even at a young age, causing further damage to this young man's confused psyche. The bipolar nature of his mother, one minute showing compassion, the next resentment, encapsulates both the dehabiliting effects of drugs and the importance of strong role models and/or family, making Moonlight not only an indictment of this cultures' disdain for homosexuality but also the disintegration of family due, at least in part, to the "war on drugs". In the final segment of Moonlight we come to find that Chiron has essentially become what he never intended to be, assimilating into this drug culture where toughness and violence are celebrated. For me it's the most powerful segment of the film, as Chiron reconnects with Kevin, and eventually begins to show traces of his true self, not what others, or collective culture, wants him to be. Visually, Moonlight is striking, with Jenkins using a heavy dose of camera movements that combined with a moody, atmospheric score, effectively capture the psyche and emotions of this character in a unique and compelling structure. If I had one complaint, it would be the bully character in the 2nd segment, who feels very out of place, inorganic, and one-dimensional, only there to move the story forward. His antics mimick those of an uncaged animal, intent on stirring up violence, and while I'm sure these characters do exist, the film could have still done a better job at developing his disdain for Kevin, which felt very simplistic compared to all the other characters in the film. Barry Jenkin's has constructed a story of bristling emotion and artistic precision with Moonlight, a film that isn't afraid to play with structure, delivering a rhythmic and heartfelt examination of the importance of individualism and finding onself amongst the noise of what culture and society expects one to be.  André Téchiné's Being 17 is a complex, mature portrait of the human experience, an honest story about the importance of one being self-assured in their convictions, while having the confidence to be comfortable in one's own skin. The story is centered around two boys on the cusp of adulthood in Thomas and Damien, who couldn't be more different on the surface. Damien lives a comfortable life with his mother Marianne, a doctor, and while the stresses of his father being on a tour of duty abroad are felt, Damien is a character who seems to have his life together, getting good grades in school and having a strong, healthy relationship with his mother. Thomas on the other-hand has a more modest living, a young character who has been tested by fire, walking long distances through the mountains everyday to get to school, only to return home to work into the night on the family farm. Adopted, Thomas has resentment for his parents and the situation he finds himself in, with his internal angst leading him to bully Damien at school, someone who he views as pretentious due to his more privileged upbringing. When Thomas mother falls ill, the two boys unexpectedly find themselves sharing the same roof, after Marianne treats Thomas' mother and decides it's best if Thomas comes stay with her until his mother gets better. Calling Being 17 merely an LGBT film massively discredits what André Téchiné has accomplished, being a film that touches on universal truths of life and adolescence, while simultaneously reflecting on the unique challenges which plague the homosexual community when it comes to sexual discovery. Being 17 is a film that unfolds naturally, never rushing towards its themes or ideals, instead letting its young characters' discover themselves as the narrative unfolds, exhibiting the curiosity, angst, and overall confusion that is a part of adolescence, which in time ultimately leads to self-discovery. Thomas' characterization is they lynchpin, the driving force behind the film, and the main reason that the whole experience feels organic. Intriguing and compelling from the opening frame, Thomas is a character whose angst and frustration towards Damien makes their inevitable feelings towards each other believable, being a character who is in a state of denial about his sexual identity, due at least in part to his more difficult upbringing and the resentment he feels towards those he perceives to have a better life than him. He is attracted to Damien yet he shows it in aggressive ways, often psychically lashing out, with the film subtly capturing the toxic nature which masculinity-fueled aggression can have on thoese trying to discover their sexual identity. It's only through tragedy that Thomas begins to understand that his angst towards others is rooted in selfishness, being a character who beings to see how everyone is struggling in some way or another, and for the first time offering compassion for others. Being 17 is elliptical, poetic, and heartfelt, with a narrative that comes full circle in its conclustion, with Thomas now having to be the emotional rock for both Damien, and his mother Marianne, who both towards the end of the film find themselves riddled with the same form of grief and anger that plagued Thomas. André Téchiné's direction and visual design further serves to elevate the overall experience and emotion of Being 17, which features rugged camerawork early on, such as handheld photography and an array of dirty compositions, cinematic devices that effectively evoke the internal struggle of Thomas. Téchiné's use of tight compositions throughout the film are subtle but effective as well, evoking a sense of intimacy that would otherwise not exist, a decision that perfectly matches the complex and personal emotions of this story. For much of the film, Thomas' only place of peace is one of solitude in the countryside, with Being 17 featuring beautiful photography of the snow-covered landscapes, with Techine using wide-compositions in these moments that perfectly mimic the psyche of the character of Thomas, a young boy who feels alone. A complex, heartfelt story that works on nearly every level, from direction, to acting, to story, André Téchiné's Being 17 may in fact be the filmmaker's most impressive film to-date, offering up a mature study of adolescence in which calling it a "coming of age story" or "LGBT story" feels too restrictive given the films' universal merits. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed