Tony Vainuku & Erika Cohn's In Football We Trust is an in-depth documentary which chronicles the lives of four young Polynesian men, each of which dreams of playing Football in the NFL. Offering a snapshot of the Pacific Islander pipeline in the NFL, In Football We Trust is an intimate and engrossing American immigrant story which uses an observant eye to document the pressure these young men have to provide and support their family. Growing up in an area where gang violence and poverty cripple many families, Football is viewed as a form of salvation by many Pacific Islanders, a potential way out of the tough life they live. As one of the the fathers states in the film, "football isn't a way out but a way up", and one of the greatest attributes this film has is its ability to capture the unbelievable weight that is put on the shoulders of these teenage boys, each of which carries the burden of being relied on to make a living and provide for their families through football. While watching this film, the pressure these kids have is palpable, coming not only from their own families but also the community around them which expects so much from them on the football field. While all four characters the film document struggle with a lot of the same challenges, each individual does bring their own unique challenges as well, with the film doing a wonderful job of being an honest, unbiased observer to the plight of these characters, never really showing a biased or truly showing an opinion of the plight of these characters, only being interested in telling their story. For some of the characters Football offers a release, something to focus on outside of the gang violence and poverty which surrounds them, while other members of the documentary seem to use football more as a form of controlled violence. From a filmmaking perspective, In Football We Trust is a pretty straightforward documentary but that doesn't mean it isn't compelling, as the film manages to show a lot of heart, examining these young men who have a monumental amount of pressure to succeed. Compelling, observant, and in-depth, In Football We Trust chronicles the maturation of four young men from high school football to the high stakes world of college recruitment, capturing the effect which societal expectations can have on young men.

0 Comments

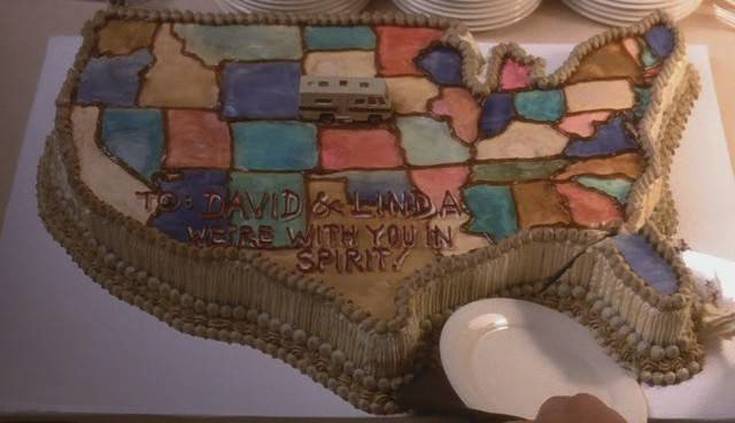

Perhaps the quintessential mid-life crisis film, Albert Brooks' Lost in America tells the story of David and Linda, a married couple who share a cushy existence in Los Angeles. When David finds himself passed up for a big promotion, he lashes out, convincing his wife to sell everything they own and hit the road in an attempt to "see America". As a gesture of their commitment to "starting over", David and Linda plan to remarry in Las Vegas, which ironically enough is the beginning of the end of their attempt to start over. Albert Brooks is without question one of the best satirical filmmakers of his era, and with Lost In America he has created a quietly-biting film about the deteriorating American idealism of the 1960s. Through amusing comedy, Lost In America quietly eviscerates the capitalist ideals of success, where materialistic aspects define a persons' worth, as these character's suffer through much of the film thanks to their reliance on money. It's no coincidence that David and Linda's idealism of being free from the chains of society becomes shattered in Las Vegas, a place which could be described as the heart of the darker aspects of the American dream where a money-obsessed generation fills the casinos on a nightly basis. Linda loses their life's savings in Vegas, which sends the couple spiraling out of control, and it becomes apparent that this yuppie couple simply can't survive without the comforts of money, which in turn finds them heading towards New York where David essentially begs for his job back. Typical of Brooks, the script of Lost in America is sharp and witty, featuring lots of great dialogue throughout, but while Lost in America is certainly funny and an entertaining experience from start to finish, Lost in America feels slight when compared to some of Brooks' best efforts, even when considering its underlying angst centered around America's obsession with monetary success. Lost in America is a film which appreciates and salutes those individuals who aren't afraid to drop out of the consumer, capitalist-driven society America has become, but perhaps the most interesting aspect of the film is Brooks' himself essentially acknowledging that while he appreciates this ideology and is certainly frustrated by how America has become, he himself would never be capable of following through on this type of idealism  John Sturges' Bad Day At Black Rock is a tight, fast-paced mystery/thriller that tells the story of John J Macreedy, a mysterious one-armed stranger, who arrives by train into the small, dusty, backwater Arizona town. On his arrival, Macreedy heads to the local inn where he asks for the address of a Mr. Komoko. From that moment on, Macreedy is met with nothing but inhospitality by nearly every member of the town, picked on at every turn by henchman of Reno Smith, a cool, calm demeanored man who clearly owns most of the town's land and business. I'm not sure there is a better example of pacing than Bad Day At Black Rock, a film that starts fast and never wavers. Even the opening sequence to the film is photographed with visceral energy, a simple sequence of a train heading through the barren desert landscape which is shot with such energy and vigor, giving the impression that this train is barreling down on the small town, creating a sense of intrigue and mystery from the opening frame. Bad Day at Black Rock is lean and mean, so tightly paced that I really can't think of a single moment that feels superfluous or unnecessary. Relying almost entirely on dialogue, Bad Day and Black Rock features a host of memorable performances by actors such as Lee Marvin, Robert Ryan, and Ernest Borgine, each of which effectively chews the scenery up as members of this small town, eatch of which seeing nothing but the worst possibilities from John J. Macreedy's arrival. Featuring very litlte action, Bad Day At Black Rock relies heavily on intrigue, essentially teasing the viewer for much of its running time, making it clear that the men who occupy this small town have something to hid, but only hinting at what this is, which in turn makes Bad Day At Black Rock one of cinema's great teases. While the script and performances are all around strong, what makes Bad Day At Block Rock so special is its ability to capture the absolute absurdity of xenophobia through this small town culture. This is a film that beautifully exhibits the destructive nature of group think, exhibiting how small town communities close in on themselves, expressing almost a tribal mentality of ugliness which effectively alienates and creates villians of anyone from the outside, stupidly declaring that they simply don't belong. One of the my favorite aspects of this entire film is the decision by the filmmakers to give John C. Macreedy a deformation, with his lack of a left arm making him different and something which the small community can focus on. Macreedy severed limb is essentially a symbolic representation of xenophobia and racism, with the various members of the small town focusing in on this deformity, acknowledging this flaw, picking at it much to the chagrin of Macreedy, using it as a crux to define why Macreedy himself doesn't belong. While one can't argue that Bad Day on Black Rock wears its message on its sleeve, this is a film that is lean and mean, being both a tense mystery/thriller full of strong character acting and a sharp dialogue, as well as an important film about the shortcomings and absurdity of xenophobia.  Philippe Garrel's In The Shadow of Woman tells the story of husband and wife Pierre and Manon, a happy couple, who live and work together as documentary filmmakers. When Pierre meets Elizabeth, an intern at the film archives, he becomes transfixed on her beauty, striking up an affair with the young woman to satisfy his sexual urges. Now having a mistress and a wife, Pierre is satifisied, that is until he discovers that Manon herself is having an affair of her own. Philippe Garrel's In The Shadow of Woman is a quietly profound study of the male psyche that uses a deceptively simple premise to comment on the insecurities and hypocrisy which exist in the male ego. The film itself isn't told by through a character's point-of-view, rather the relationship itself is very much the central character, as Garrel dissects the dependency, deceit, complacency, and companionship which evolves in any long term relationship. While dealing with complex emotions, In The Shadow of Women plays more like a comedy at times than a tragedy, with the filmmakers focusing on the absurdity and hypocrisy of the male ego. Pierre is a character who accepts his infidelity as simply a character trait of being a man, yet he becomes utterly possessive and outraged when he learns of Manon's affair. Through this sordid affair, In The Shadow of Women manages to capture the differences in psyche between man and woman, with Pierre being fueled much more by his primal impulses while Manon's affair is predicated on the need to feel more appreciated, wanted, and loved. While I understand how what I described sounds a bit conventional and rigidity simplistic, trust me, as the way these characters interact and the story unfolds, In The Shadow of Women is everything but that, being incredibly human, organic, and potent. While some may find the film a tad slight, I'd argue that In The Shadow of Women is really a film that is quietly brilliant, being truly about the importance of intellectualism, as the character of Pierre struggles to resist his primal, carnal urges. Throughout this story it's never questionable whether Pierre loves his wife, but he lets these animalistic impulses of desire control him, which in turn leads to inevitable strife and turmoil, both in their relationship and in his inner psyche. Subtlely profound, Phillipe Garrel's In The Shadow of Women uses a borderline comedic tone full of wit to deliver interesting evocations on the human psyche, focusing on the differences and similarities of the male and female mindset which exist in any relationship.  Perhaps Claire Denis most enigmatic experience, The Intruder is a film of very few words, relying heavily on its visuals to tell its mysterious story of one man's inner strife. The film is centered around Louis Trebor, an elderly man who lives a fairly self-sufficient existence with his dogs in the forest near the French-Swiss border. Louis lives a life of solitude and while it's never truly outright stated, it's clear he was a man who neglected his son, who lives nearby but is a far more attentive father to two young children. Told in an elliptical nature, where stretches of the film are linear while others jump across the timeline of this man's life, The Intruder is an impressionistic film which gives the viewer absolutely nothing outright, offering instead a moody portrait of a man's inner turmoil. The film feels a lot like a dream, and besides Louis' son and his daughter-in-law, The Intruder intentionally makes it hard to decipher exactly how much of what we are witnessing is in fact reality and how much is a figment of this tortured soul's imagination. The elliptical narrative certainly doesn't help the film's clarity either, with the viewer forced to pay attention to small details such as the formation of scars, the changing of the seasons or locations as a a guide to help piece the story together. The film spans continents and time lines, being a story that is grand in setting but incredibly intimate in its exploration of the grisly character of Louis. Perhaps The Intruder is best described as a mood piece of isolation, solitude, loss, and regret, forcing the viewer to attempt to put the pieces together of a man's fading life. Through stillness and silence, The Intruder offers a glimpse into the psyche of a man who is deteriorating both physically and mentally, traveling to various parts of the globe where he seeks redemption and some form of peace, though it remains just as elusive as the film itself. Through impressionistic cinematography which uses an array of tight compositions and Michel Subor's cold and quiet performance as Louis, The Intruder evokes a sense of sorrow and regret, with the atmospheric soundtrack only adding to the dreamlike experience. For me, The Intruder is an impressionistic study of the regret and inner turmoil, commenting on how our worst enemy is often ourselves, with Louis as a character simply attempting to come to terms with his past mistakes, most notably the neglect he showed towards his son. One could even argue that the heart transplant itself is merely a metaphor for a man without a heart, a man whose life has been fascinating but ultimately directionless and empty, a character who intruded on the lives of others he cared about with little real empathy. While it certainly could be described as a somewhat meandering piece of existentialism, Claire Denis' The Intruder is a beautifully rendered examination of the emotions and fears of a broken old man, one thats elusive flow is bound to create a host of varying opinions as to what exactly Denis is trying to say.  Roberto Minervini as a filmmaker has always been fascinated with America's unwanted and forgotten individuals, most commonly those residing in the rural areas of the deep south. For Louisiana (The Other Side), Minervini profiles Mark and Lisa, a couple living in the backwaters of Louisiana, each struggling with addiction while they live well below the poverty line. Lousiana is a film that doesn't hold back in capturing the troubling underbelly of the deep south, where anti-government zealots, drug addiction, racists, drunks, and deeply confused individuals have taken a strong hold in the backwaters and small towns of this rural landscape. While a sight to behold, the setting and circumstances of what Minervini is documenting is quite ugly, but the filmmakers never show any judgement, focused solely on documenting these individuals, many of which feel abandoned by modern society and a government they don't support. While I wouldn't call Minervini's film sympathetic, Louisiana does show an appreciation for this wounded community, with cinematography that subtly captures the beauty in this desolate, ugly setting, using beautiful compositions and the overhanging sun, which shines a bright light on this desolate community of outsiders. Minervini's film never shys away from the ugliness, instead it attempts to find the underlying beauty in this repugnant setting. The access which Roberto Minervini is granted is truly impressive, which leads to some pretty startling imagery and a few moments that will be hard to forget, one in particular being when Mark shoots up a stripper with a shot of heroin before her performance on stage. While much of Louisiana (The Other Side) feels like an expose in ignorance, tender moments do exist among the darkness. Mark's relationship with his elderly grandmother and mother being one of them, as Minervini captures the affection and love he has for these two woman. Sparked by his mother's elderly status and impending death due to cancer, one of the most powerful scenes of the film involves Mark vocalizing his struggles with addiction, his desire to be clean and get his life together. Everything he says feels genuine, but there is an uneasy sense that he won't be able to get his life together, stuck in the grasp of addiction. In a way, Mark's plight is an important aspect of Lousiana (The Other Side) because it pulls the film away from feeling exploitative, adding a level of tragedy to the story of a man whose addiction to drugs is unshakable. If you haven't figured it out already, Roberto Minervini's Lousiana (The Other Side) is a unique documentary in that while it's observational and does a great job at exhibiting the world which these characters inhabit, I found myself sometimes questioning how many situations or scenes were constructed in an attempt to aid the filmmaker in reaching his desired level of impact. Mark, a small-time meth dealer and ex-felon, is certainly being himself, but because of the unique nature of Minervini's film, scenes feel constructed, though I'd be hard pressed to argue that they don't feel rooted in the realism of Mark's experiences, thus I'm not sure how much it matters. Roberto Minervini's Lousiana (The Other Side) attempts to exhibit the fringes of society, on the border of illegality and angst, documenting a group of men and woman who have fully embraced the decay of society.  Not to be confused with the Leopold Von Sacher-Masoch classic of the same name, Jesus Franco's Venus in Furs is a stylish, atmospheric thriller that tells the story of Jimmy Logan, an American jazz musician, who while in Turkey discovers the body of a dead girl on the beach. The woman, Wanda Reed, has been murdered by a group of the economically and socially elite, something which Jimmy may or may not have witnessed when attending an upper class party a few months ago. Now in Rio de Janeiro, Jimmy shacks up with Rita, a beautiful singer, who helps the young musician recover his equilibrium from the events he witnessed in Turkey. Jimmy is mentally back on his feet, that is until Venus, a woman who is a dead ringer for the deceased Wanda Reed, walks into his life. Jesus Franco's Venus In Furs is atmospheric, entrancing, and full of intrigue, being a film which may be a little hard to follow at times, though it hardly matters due to the visual and audio atmospheric qualities it's able to create. Venus in Furs is essentially a ghost story about a vengeful spirit in the form of this dead woman who exacts her revenge on those who wronged her. The inclusion of Venus, who is a dead-ringer for Wanda, adds a wrinkle to the archetypal ghost story though, as the film never makes it very clear whether Venus is in fact there or whether Jimmy's infatuation with Wanda has led to psychological manifestations. The film is full of mystery and intrigue early on, being a psychological thriller that never fully becomes clear until the tacked on ending, though Jimmy's obsession over this woman is a major aspect of the film. In one word, Venus in Furs is intoxicating, with Jesus Franco's direction, along with psychedelic musical choices and stylish cinematography working together create an atmospheric experience. Using blurred imagery, innovative cinematography both in terms of composition and movements, Franco evokes a sense of entrancement that envelopes the whole film, putting the viewer into the psyche of Jimmy Logan, a man who can't get this beautiful woman out of his mind. For lack of a better word, the film creates an intemperance in the viewer, evoking the inner-psyche of its main character, a man who becomes intoxicated and borderline obsessed by Venus. Typical of a lot of these types of films, Venus In Furs doesn't really make complete sense, with the ending not exactly being earned, but I'd argue that it hardly matters in a film like this, which is an impressive cinematic achievement more so because of the atmosphere and mood it is able to create with its excessive style which surely delivers a one-of-a-kind experience. This isn't to say the film doesn't have merits outside of its style, as Franco's use of eroticism seems to be a playful jabbing at the Philistine or uptight culture of Art House cinema. I may be reading into the film too much, but the fact that the characters who are responsible for Wanda's death are all socialites and members of high society, one could argue they are a symbolic representation of this ideal, being characters who are Erotic and sensual behind the curtain but cold and proper on their outer appearance. Highly-stylized, moody, and full of intrigue, Venus In Furs is another fascinating film by Jesus Franco, who seemingly uses his typical eroticism to comment on the uptight conservatism of his peers.  Ben Safdie & Joshua Safdie's Go Get Some Rosemary is an independent film in the vein of John Cassavetes, being a loose narrative that doesn't have much interest in plot plots, instead focusing on its characters and story. The film is centered around Lenny, a 34 year-old father to two children, who is barely living a sustainable existence. When not getting harassed by his boss for his inattentiveness at work, Lenny lives a life of mostly solitude in a small, decrepit apartment. Divorced, Lenny seems repelled by any true sense of responsibility, which makes things a bit complicated when he takes care of his two young sons, Sage and Frey. The opening scene of Go Get Some Rosemary is simplistic, but a perfect example of effective low-budget storytelling, following Lenny as he buys a cheap, footlong hotdog from a small-time vendor. The sequence may seem superfluous to some, but it's the details, such as how he pays for the hotdog with what amounts to loose change, that reveal Lenny as a character. As he leaves the hotdog vendor he attempts to scale a fence, unsuccessfully falling down to the ground and losing his hotdog to the ground in the process. While many adults would shrug their shoulders at their own stupidity, Lenny laughs manically like a child about the situation, than proceeds to consume his hotdog anyway. This opening sequence masterfully captures Lenny as a character, a man of little ambition, who finds himself easily sidetracked from any type of responsibility. Lenny is a character who is essentially a big-child, void of nearly all responsibility, which makes things a tad complicated once a year when he is asked to take care of his two young sons for a few weeks. Go Get Some Rosemary follows the offbeat adventures of Lenny and his two young children, oscillating between Lenny's kindness and tenderness towards his kids and his utter-incompetence whenever he is faced with any type of obstacle. Calling Lenny a competent father would be a bit of a stretch, but Go Get Some Rosemary beautifully balances the line of parental competency, as Lenny is a character who without question cares for his kids, showing tenderness and love towards them, but he is also a character who routinely puts his children in danger, constantly dragging them into situations no father should. The reason Go Get Some Rosemary is such an engaging film is that Lenny as a character seems oblivious to the fact that he is such a poor parent, at times showing an exuberant amount of love for his children while neglecting them in the very next scene. It's almost as if he treats his children like a mutually-aged friend, expecting that they are capable of taking care of themselves while simultaneously loving to spend time with them. Go Get Some Rosemary has the same naturalistic approach one has come to expect from the Safdie brothers, using primarily handheld photography and an intentionally rugged use of focus which gives the film a more gritty, lived-in feel. The aesthetic is especially necessary in a film like this, as this amateurish, gritty aesthetic evokes a visual sense of who Lenny is as a character, a borderline low-life, who inhabits a crummy, rat-infested apartment. It is never stated but one can assume that Lenny has never been the same since the divorce for the mother of his children, falling down a dark hole after finding himself alone, repelling responsibility as a coping device. While Go Get Some Rosemary certainly takes a bit of time to come into focus, this is a compelling film from the Safdie brothers, that is part off-beat comedy, part resonant character study about a character who is defeating himself on a daily basis.  Tobias Lindholm's A War is the story of company commander Claus M. Pedersen, who heads up a unit stationed in Afghanistan. During a routine mission, one of the youngest men of the company is killed, leaving the moral of the soldiers in shambles, with many of these men struggling to keep their heads on straight in such chaotic circumstances. In an effort to regain stability of his unit, Pedersen opts to accompany his men on some of these patrols, effectively boosting the moral of his men through effective leadership. On one such routine patrol, Pedersen and his men find themselves caught in a heavy crossfire and in order save the lives of him and his men, Pedersen orders for an airstrike on a compound, one in which he isn't 100% sure is hostile. This decision, one which was made under extremely intense circumstances, has grave consequences for Pedersen and his family back home when it's revealed the combine was at least, in part, occupied by innocent civilians. Tobias Lindholm's A War is a powerful story of the murkiness of war, being a film that manages to be both a dynamic action drama and an important examination of the true horrors of war. With the first half of the film splitting time between Afghanistan and Pedersen's family back home in Denmark, A War paints an effective portrait of the far reaching nature of War, examining not only the men who serve and the effect it has on their psyches, but also that of their families back home - the wives, sons, daughters, mothers, etc, who each struggle on a daily basis, not only worrying about the safety of their loved ones but also missing the support they provide. While Pedersen is without question the central character of this film, A War still makes sure to give its supporting roles dimension and depth, offering up screen time to the various members of Pedersen's unit, many of which are struggling with issues of fear, homesickness, and emotional solitude. While this evocation of the life of a soldier and the emotional toll it can create is the main focus of the first half of the film, A War really soars in the back-half, when Pedersen finds himself facing potential war crimes. From the viewers perspective it's known that Pedersen did not have the full confirmation necessary to order that airstrike, and in terms of military law he should face the consequences, but what A War manages to do so beautifully is remind the viewer just how unfair it's to expect men in chaos to act by these laws written by bureaucrats in desk-chairs. A War captures how these rules of engagement, while necessary, completely ignore human error under extraneous circumstances, offering up a straight-forward, easily definable code for a situation that is everything but. The chaotic nature of conflict makes these type of decisions much more difficult to define, and it's quite frankly laughable for us as bystanders to pretend that we have any idea the circumstances of these decisions, and pretend we would act any differently. We, as a society, pretend that training is enough to prepare men for these types of decisions but that simply is naive, as in times of extreme chaos and potential death, the primal desire to survive takes over, regardless of training, becoming the number one priority. That isn't to say that A War completely absolves Pedersen from his decisonmaking that day, which led to the death of innocent civilians, it simply acknowledges that there are never easily definable answers under such chaotic circumstances of War, something which I think many people, regardless of politics, need to comprehend. With that in mind, A War ends on powerful note, as Pedersen finds himself acquitted of war crimes but is unquestionable faced with the torment of continuing to live with what he did. The final shot, a dark silhoutte of Pedersen alone on his patio beautiful captures this, visually expressing a character who is forced ruminate over the lives he inadvertently took. Featuring intense action, fast-pacing, and important ruminations on effective decision-making under the extreme circumstances of wartime, A War is multi-layered examination of the far-reaching aspects of War and military conflict, offering no easy answers when it comes to lives and deaths of human-beings.  Nicholas Hytner's The Lady in the Van is a pleasantly entertaining film that is both funny and tender, owing a large amount of its success to the brave and dimensioned lead performance by Maggie Smith. Based on true events, The Lady In the Van tells the story of a relationship that unfolded between Alan Bennett, a writer, and Miss Shepherd, a homeless woman of unknown origins who ended up parking her van in Bennett's London driveway, proceeding to live their for 15 years. Light and playful in tone, The Lady in the Van lets its incredible true story and impressive lead performance do most of the work, documenting the relationship between two unlikely individuals. Ms. Shepherd isn't the most likable of characters, being abrasive towards everyone around her, and the film deserves credit, along with Maggie Smith, for its ability to make the viewer emotionally attached to understanding and feeling for this character's troubled past. While Maggie Smith's central performance is without question the main attraction, The Lady in the Van works so well because of Alan's characterization, which I would argue is even stronger. A single man, Alan essentially lives a life of solitude as a writer, and I particularly found the comparisons this character makes between his own mother, who lives in a retirement home, and his relationship with Ms. Shepherd, who lives in his driveway, to be both fascinating and emotionally compelling. Early on, I didn't think that The Lady in the Van did a great job balancing its comedy and drama, but as Alan and Miss Shepherd's relationship progresses, the film manages to reach stronger moments of poignancy while still finding the humor in Miss Shepherds abrasive personality. My main complaint with The Lady in the Van is that it never quite manages to thematically explore societies judgmental tendencies with the less privileged, touching on it in direct ways but never diving beneath the surface, almost as if the filmmakers assumed the main relationship between Alan and Miss Shepherd would be enough. One thing that did surprise me about The Lady in the Van is the amount of style and chances the filmmakes make, even having a few well-executed surrealistic moments that elevate the film when it become a little didactic at times. With a very strong central performance and a touching story, The Lady in the Van is compelling and tender, even though I couldn't help but wish the film would have gone a little further in deconstructing societies taboo with he less fortunate. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed