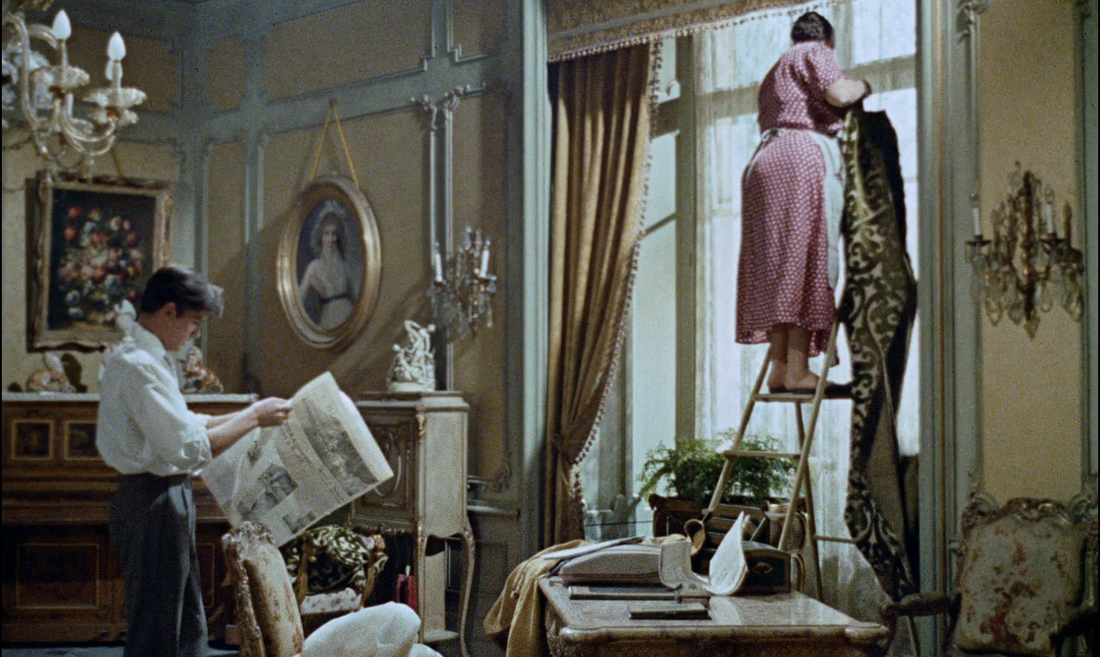

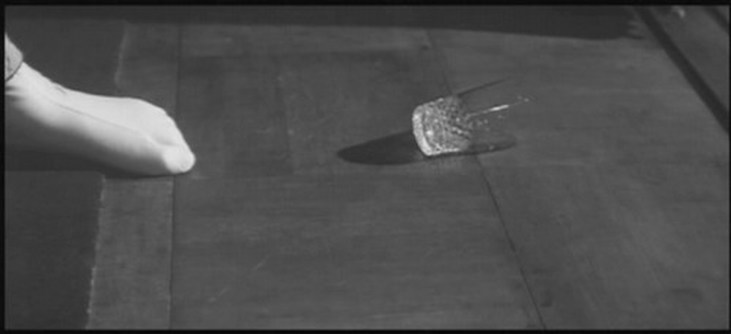

René Clément's Purple Noon is a devilish little thriller about Tom Ripley, an American who travels to Europe in an effort to convince his friend, the roving playboy Phillippe, to travel home to San Francisco at the request of his wealthy family. On Tom's arrival in Italy, the two old friends immediately reconnect, spending a jovial night on the town, much to the chagrin of Philippe's fiance, Marge. Tom and Phillipe's relationship is introduced as jubilant and intimate during their rendezvous, having lots of homoerotic undercurrents, but as the booze runs low, along with Tom's funds for being in Europe in the first place, it becomes increasingly clear that Phillippe and Tom's relationship may not be as close as we were led to believe, leading to tension as it becomes clear that Phillippe has no intentions of returning to the United States. Considering how much Tom is enjoying this extravagant lifestyle, one that is funded by Phillippe's financial state back home, this revelation leaves Tom left to evaluate his options, something which slowly reveals the nefarious nature of Phillippe and Tom's relationship, one built on envy and obsession. I don't remember Anthony Minghella's The Talented Mr. Ripley well enough as a film to draw detailed comparisons and I haven't read Patricia Highsmith's novel, but if memory serves me correctly (no promises), Purple Noon is a significantly better film in nearly every way that Minghella's adaptation, as Clement has created a clever, intoxicating thriller thats craft, acting, characterization, and narrative pacing are all vastly superior. One of the main things that stood out to me about Purple Moon is Clement's wonderful use of composition throughout, tactfully framing his film in ways that evoke the emotions of characters or the circumstances which they inhabit. My favorite example of this is Clement's juxtaposition of the mirror scene (pictured above) with a scene on the boat in which both Tom and Phillipe's are engaged in conversation, both their heads stuffed into the composition. With both compositions being eerily similar in terms of spacing and placement, and both taking place before the murder of Phillipe, Rene Clement is telling the story visually, foreshadowing Tom's envy and attempted identity transference through imagery, something which wouldn't be particularly noticeable to the novice viewer. When Tom goes through the arduous task of ditching the body of one of Phillipe's friends who gets too nosey, Clement repeatedly has the composition focusing solely on the feet of Tom, evoking a primal understanding of what is transpiring in front of the viewer, as we see one pair of feet struggle and strain to drag another man's body across the floor. It's a tad hard to explain, clearly, but the choice of composition is more visceral and expressionistic, a "boot in the dirt" type of photography that strips Tom of his identifiable features, like his face, showing the disposal of a body on the most pure, basic form. Alain Delon is great in this role too, his boyish good looks and general demeanor exquisitely masking his underlying envy and obsession. Delon's performance is subtly terrifying because of his mild-mannered, cool approach, with the film routinely showing flashes of his more diabolical state, but doing so in a way that never makes it entirely clear whether Tom is simply a deceptive con artists or a psychologically disturbed individual. The film's ability to blur this line is one of its stronger attributes, with Tom's actions indicating that both factors are more likely than not a piece of that puzzle. From the intrigue of the relationship between Tom and Phillippe early on, the homosexual undercurrents and mysterious tension, to the escalation of Tom's attempted identity transference after Phillippe's murder, simply put, Rene Clement's Purple Noon is an effective, diabolical thriller that is well acted, well crafted, and well told, being a film that keeps the viewer engaged from start to finish.

0 Comments

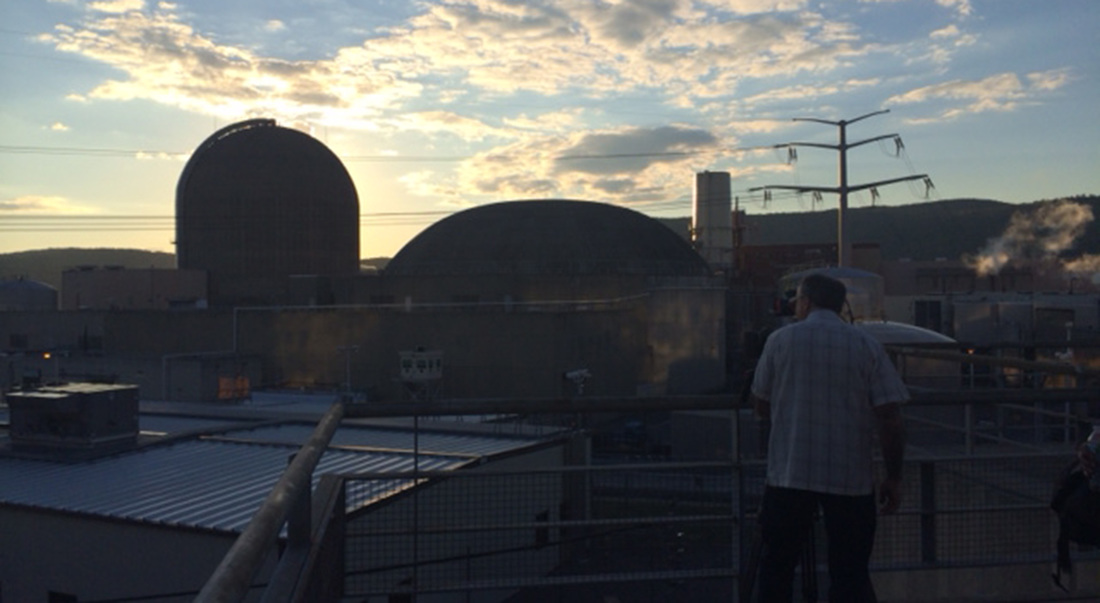

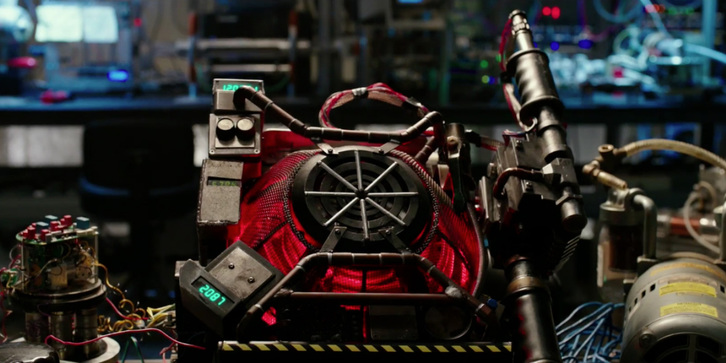

While I consider myself somewhat of a novice when it comes to Mikio Naruse, having explored the canon of nearly every other titan of Japanese cinema far more by comparison, the one thing that always seems to stand out when it comes to this celebrated filmmaker is the touch of delicacy and grace that seems to envelope much of his work. When A Woman Ascends the Stairs is no different, being a tender, humanist study of one young woman's struggles in an unforgiving society. Set in 1950s Tokyo, When A Woman Ascends The Stairs takes a naturalistic approach, chronicling the life of Keiko, a woman who works as a bar hostess in Tokyo's Ginza district, entertaining businessmen after work . Regardless of being sharp, resourceful, and strong-willed, Keiko struggles mighty to find her own sense of independence through both personal and financial freedom, falling victim to the oppressive system she inhabits, no matter how hard she tries, one that is completely dominated by placing men atop of the pedestal. Lustrously photographed in monochrome and featuring elegant direction from Naruse, When A Woman Ascends the Stairs is a quietly devastating drama which paints a rather harrowing portrait of woman during this era of Japan, one in which their successes and failures were inherently linked to their relationships with men in their life. There is nothing abrasive or overly dramatic about When A Woman Ascends The Stairs, rather a sense of calm, steadfast execution, being a film that lulls you to sleep in a sense as it evokes the entrapment felt by its main protagonist. For Keiko, her choices begin to appear quite simple, either get married or struggle to makes ends meet. In an effort to establish herself independently, she attempts to buy a bar of her own, but it becomes apparent that even this will be extremely difficult, due to her family routinely hounding her for money, and the continually debt she accrues by simply performing her job as a barmade/hostess in order to evade becoming a woman of the night, if you know what I mean. While When A Woman Ascends The Stairs is quite harrowing, following the ups and downs of Keiko's struggles for independence as a woman, the film never falls into a sense of despair, nihilism, or even pessimism, with Naruse optimistic spirit ringing out in the final frames, as Keiko herself keeps on pushing forward, optimistically believing that she will someday own her own bar, and by proxy her own independence form this male-centric culture. Beautifully photographed and exquisitely understated, Mikio Naruse's When A Woman Ascends The Stairs is a powerful showpiece of Mikio Naruse's filmmaking, being a film that is harrowing, yet optimistic, encompassing the range of emotions associated with a hard-working individual being a victim of the system.  John Waters' Female Trouble is a vile, grotesque, and hilarious story about the life of Dawn Davenport, a self-centered young woman that transforms from a relatively modest schoolgirl into a mass murder, all of which stems from her intense desire to become famous. The film begins in her high school days, where Dawn, played by John Waters' regular Divine, the 300-pound transvestite, obsesses over cha-cha heels. On Christmas Day, Dawn goes ballistic when her parents' refuse to buy her the heels, due primarily to their preconceived notions about "the type of girls who where cha-cha heels", leading Dawn to hit the road and never look back. From there, Dawn is raped, becomes a single mother, a criminal, a glamorous model, and eventually a mass murder who gets a hot-date with an electric chair, with John Waters' absurdest comedy painting a vivid and vile portrait of self-indulgence. Being one of John Waters' early efforts, aka pre-Hairspray, Female Trouble is an exuberant yet rickety-made piece of filmmaking, a film that looks and feels amateurish yet lively, relying on Divine's flamboyant energy and visceral rage to create a sustained aura of shock and awe, as the film delivers Water's one-of-a-kind satirical flare. Female Trouble is a film that was made to shock and offend, a social commentary wrapped in disgust that comments on the pitfalls of self-indulgence, related to not only to morality but also art itself. John Waters has always been a filmmaker that never succumbed to the elitist, pretentiousness mindset that plagues so many great artists, being a filmmaker who routinely finds truth and intellectualism in what is perceived to be grotesque and repugnant. On some level, Female Trouble is a commentary on the pretentious, self-indulgences of the art world, with Dawn becoming a character so obsessed with being respected and admired as an artist that she is willing to kill or be killed to do so. Flamboyant satire is what Divine was made for, and she delivers in spades throughout Female Trouble, carrying the film with her undeniable energy, lamenting at the end, "the death penalty is the best reward I could ever recieve for my work". Like many of his John Waters' features, Female Trouble is a film full of subversive energy, being a story that loudly skewers societies norms on family, beauty, and sexuality to tell its absurdest story of Dawn, revealing how vanity itself is often a bedside companion with selfishness and hate.  Justin Lin's Star Trek: Beyond picks up in the middle of the USS Enterprise's five-year mission into uncharted territory, finding Captain Kirk and his crew arriving at Starbase Yorketwon, a remote outpost on the fringes of Federation space. When an unexplained frequency from deep space is discovered, the USS Enterprise volunteers to explore the peculiar signal, unknowingly venturing into a trap that leaves the Enterprise completely destroyed, with much of its crew stranded on an unknown planet. With no means of communication, limited supplies, and no apparent means of rescue, Kirk and the other survivors of the USS Enterprise are forced to ban together, using their wits in order to defeat this new, unknown enemy who seems to have a lot of hatred for the Federation. Justin Lin's Star Trek: Beyond is a tightly-paced, action-packed thrill ride that should appease most fans of large-scale science fiction adventures, though it may leave some of Star Treks more devout fans grasping for straws, due to the film's breakneck pacing and overall lack of intelligence. There is an intellectual bankruptcy to Star Trek: Beyond, in that Justin Lin shows very little interest in any real form of characterization, outside of a few strong narration moments from Kirk, with the film feeling like a sequence of strung together action set pieces first, relying on the past film's character development to supply the emotion and drama of this story. The characterizations that do work, work due to their reliance on the actors and the relationships built through the prior films in the series and the overall brand, with basically every new character in the film, specifically the main baddie, feeling very paper thin and simply there to serve the narrative thrust of the story. What we get in turn is 120 minutes of blockbuster entertainment, with Justin Lin providing the viewer with loud and bombastic action that also feels more grounded than typical, mainly due to much of the film being spent outside the USS Enterprise. The film looks great in its big moments but it's in Star Trek: Beyond's smaller moments where film holds its footing, stripping these characters of their technologically-fueled specializations and forcing them to survive on a more primal scale, one in which communication and trust are the most paramount. Do I wish we could have had the best of both worlds? Absolutely, but I'd be lying if I didn't say I enjoyed Justin Lin's Star Trek Beyond, due to its simple, straightforward approach that is unquestionably dumb in aspects, but also very economically made, cramming a fun, explosive blockbuster filmmaking into 120 minute frame, which sadly in this day and age of blockbuster style filmmaking feels like quite the accomplishment.  Noah Pritzker's Quitters reminds me a lot of another American independent film I saw earlier this year, The Automatic Hate. While these two films have very little in common from a story, character, and thematic perspective, both films are infectiously brazen in how they tap into uncomfortable aspects of human emotion. Centered around a dysfunctional family, specifically Ben, the teenage son, Noah Pritzker's Quitters reveals how damaging emotional trauma can be on the psyche of any individual, as the story reveals subtly and sometimes not-so-subtly, the sources of Clark's emotional pain that is related to feeling like part of a failed family. In the opening sequence we are introduced to Clark's mother, an emotionally unstable woman who appears to be suffering from some severe form of mental instability or chemical imbalance. With her seeking rehab, Clark becomes further despondent, having absolutely no one to talk to outside of his father, a man who he sees as primarily responsible. The film never goes into complete detail about the father's treatment of Clark's mother, but as the film progresses it becomes clear that much of Clark's behavior, which even borders on sociopathic at times, is directly related to his inability to externalize his own frustrations about his dysfunctional family, and his father's selfishness being the root cause. After his mother goes to rehab, Clark instantly struggles to control his emotions, internalizing his anger and frustration, while simultaneously becoming vulnerable in how he immediately seeks companionship in the form of a girlfriend. This sends his presumably best friend, Etta down her own path of self-discovery when she rejects his overbearing talk of love and companionship that is clearly out of line, given their age and the nature of their relationship. Even at school Clark's interactions exhibit a sense of frustration and angst, with one memorable scene being how he attempts to comprehend why he got a B+ for his paper, poking and prodding his teacher about intricacies of grading an essay, attempting to comprehend on an ordinal scale as his teacher explains that emotion is a very important aspect that is hard to define. Quitters' brazen nature comes out when Clark essentially attempts to find a new family unit through the courting of Natalie, another classmate. Clark says and does all the right things but it becomes increasingly apparent that Clark's love is not directly related to Natalie but more about her family, one he perceives as sophisticated and well put together. I describe this behavior as sociopathic because as the film progresses, Clark becomes uncomfortably close to Natalie's parents, forming an unhealthy relationship in which he is treating them as a surrogate for his own. Quitters is a film that really forces the audience into an uncomfortable situation, watching this awkwardly unfold in a way that touches on Clark's internalized anger towards his father and his situation in life. Perhaps the best way to describe Quitters brazen style is pulp psychology, being a film that pushes the envelope of what is comfortable for a drama, in order to examine emotional trauma, mental illness, and family dysfunction. Featuring strong performances from everyone involved, Quitters' may not be the most intelligent film about a complicated issue but it's an emotionally entrancing one, mainly due to its bold storytelling.  Ivy Meeropol's Indian Point is a detailed look at the nuclear industry, focusing specifically on Indian Point, a nuclear power plant sitting merely 17 miles, give or take, from New York City. Providing an intricate look at the core activities of this aging nuclear powerplant, Ivy Meeropol's Indian Point provides a surprisingly well balanced examination of this industry, exposing crony capitalism, corruption, and simple bureaucratically negligence, focused specifically on finding answers related to the most importance question of all, are these nuclear plants safe? A rather by-the-numbers documentary, Indian Point is simply compelling due to the host of elements it untangles, focusing on how the Fukushima power plant disaster provided deadly warnings that have not been fully embraced by the federal government or the industry itself, questioning why this has occurred and the potential risks associated with this negligence. One of the more interesting aspects of Indian Point is how it exposes the Nuclear industry being almost one solely built on a lot of trust, relying on engineers to competently do their job day in, and day out, with a slight mistake potentially proving catastrophic. The film never questions their credentials, but simply suggests this isn't fair to the engineers, never cheapening itself to overbearing fear mongering, which is probably a biproduct of its balanced documentation. Indian Point interviews local residents, government employees, industry employees, environmentalists, activists, and journalists, even wisely dedicating a lot of time to the engineers who work inside these power plants. What becomes quite apparent about Indian Point is that everyone is to blame, from the government failing the industry and vice versa, due both to cronyism and straight up bureaucratic incompetence. If one example sums up the tangled web of failures in which the Nuclear industry currently sits, it's how the local government itself in New York is now fighting the cronyism of the federal government, unwilling to even risk any potential disaster when so many live in such close proximity to Indian Point. While I wish Indian Point was a little more balanced when it comes to focusing on how there are really no other competent alternatives to nuclear energy currently, the documentary casts a wide net in its depiction of the current state of the Nuclear Industry, revealing that perhaps the most frighting aspect of all this is that the industry relies more on faith than facts when it comes to safety.  Catherine Corsini's Summertime is a story about the undefinable, unclassifiable nature of love, featuring the unlikely romance between Carole, a Parisian schoolteacher and feminist activist, and Delphine, a young woman who grew up in the rural area of France, the daughter of two Limousin farmers. The film opens in the countryside, introducing us to Delphine's modest lifestyle, one in which the gender roles are strictly defined due to the environment in which they inhabit. While Delphine's father works long hours outside, and Delphine's mother handles all responsibilities on the domestic side, Delphine herself oogles one of the area's other young woman. When the source of Delphine's affection rejects her, suppressing her own lesbian tendencies due to traditonal family values, Delphine decides she needs a change of scenery, leaving the family farm for Paris. Soon after she meets Carole, instantly feeling attracted to her strong personality and outspokenness about the treatment of woman in this world. Carole's characterization is one of the weaker elements of Summertme early on, a character who becomes confused about her sexuality due to Delphine's persistent passion for her. While probably not unintentional, Summertime unwisely exhibits the close-nit relationship between lesbianism and feminism, something that really weakens Carole's characterization early on. It's almost as if the film felt it necessary to add more stakes for Carol, attempting to use her break up with her boyfriend as a symbol of her commitment to Delphine. Carole's ending of her relationship with her boyfriend is given very little focus in Summertime, a decision that weakens her own characterization. The problem is the character is also having a big discovery about her sexual orientation, yet the film never dedicates much time to exploring this moment of self discovery for Carole, a decisions that weakens various thematic threads of the film centered around homosexuality, feminism, and independence. Delphine's characterization is by far the strength of the film, being strong from beginning to end, a character whose journey is the centerpiece of the film. Delphine isn't a character who denies herself the pleasures of her sexual preference, yet she lives her life in hiding, fearful of her traditional mother and father finding out about her homosexuality. In Paris, she is alive due to being free from the gaze of her parents, yet when Delphine's father falls victim to a stroke, she immediately rushes back home to help her mother run the family farm. The back half is where Summertime gains momentum, with Carole herself finding her love for Delphine tested, being forced out of her urban environment and thrown into the polar opposite, rural environment. On the farm is where Delphine's insecurities come bubbling to the surface again, hiding her homosexuality from her parents, fearful of their reaction to her "nontraditional" sexual orientation. The strain of Delphine's festering secret and Carole's uncomfort with this rural lifestyle is where Summertime thrives, putting the couples early idyllic romance to the test in an honest and heartfelt depiction of what it means to fall in love. Through the relationship between these two characters Summertime reveals the importance of being oneself, suggesting that it can be extremely hard due to preconceived notions about homosexuality, but inevitably a necessary step in order to find happiness and love. Leaving the farm behind becomes a symbolic representation of Delphine finding her personal freedom, with perhaps the Summertime's strongest aspect being its ability to capture how hard that can truly be.  Paul Feig's Ghostbusters is a by-the-numbers, uninspired summer blockbuster masquerading as a work of feminism, a film thats characters, from top to bottom, are underdeveloped characterizations that simply serve the narrative thrust of the story. I'm all for woman having their fair share of starring roles in major blockbuster films, but can we please give them something more inspiring than this? The heart of the film is centered around the relationship between Erin Gilbert (Kristen Wig) & Abby Yates (Melissa McCarthy), two scientists who have drifted apart due to their work in studying the paranormal. When the film begins Erin is working at a prestigious university, a character who has long left behind her passion for the study of the paranormal, conforming to the bureaucracy of academia that snubs its nose at even the idea that supernatural forces are real. When ghosts begin to appear all over Manhattan, Erin reconnects with Abby, who never gave up her passion for paranormal studies, as the two leave the overbearing bureaucracy of academia to start their own business in an attempt to successfully prove that the supernatural world does exist. This film is a great example of inorganic storytelling in the way this relationship unfolds, a film that routinely tells us what we are supposed to expect instead of showing us through the characters' interactions and visual storytelling. Nothing about their relationship feels fleshed out or even earned, leading to a finale that falls flat, at least in terms of the emotional core centered around Erin nearly sacrificing herself to save her friend. While the characterizations of Abby and Erin are haphazard, the other two characters are even worse, with Kate McKinnon's one-note, oddball scientist routine grew timesome fast, while Leslie Jones' character in itself is a borderline racist stereotype. First, The Keeping Room and now this? What is with "feminist" films and their troubling characterizations of African American characters? Anyway, I would not blame the cast itself for most of these problems, as Paul Feig's storytelling acumen made it very clear that he was out of his element, with his style for improvisation becomes taxing on the viewer, weighing down the pacing of the story to a painful degree. This leads to the film having a very low batting average when it comes to comedy, as it's the type of film that assaults the viewer with jokes at an alarming rate, hoping at least some of them will stick. Perhaps improvisational comedy, to this degree, simply doesn't fit in narrative-driven, supernatural comedy blockbuster, but I'd argue the problem more lies in the filmmakers inability to recognize what jokes could be trimmed, failing to grasp the idea that less can be more when it comes to effective comedy. From an aesthetic perspective, Ghostbusters looks great, with a punchy, color pallette that is vibrant and alive, featuring a finale that certainly delivers on the action, thrills and visual "wow" factor, while also being one of the more empowering scenes as you witness these four woman laying waste to the impending threat in front of them. I'm too lazy to even touch on the troubling thematic elements of Ghostbusters which essentially says "fuck individual rights and freedom, yay big government, secrecy, and inclusion. I have no problem with political commentaries, even ones I fundamentally disagree with, but the film wants to have its cake and eat it too, as this whole idea of the government funding them aka taking control, completely rejects the film's own setup, which is related to Erin being a free thinking character who breaks free of shackles of Academia where differences of opinion are met with hostility. Paul Feig's Ghostbusters is a film in which I left the theater almost feeling sorry for the four principle actresses, being a film full on contrivances and bombastic, low-ratio humor, unfortunately ending up as just another by-the-numbers blockbuster that left me disenfranchised due to the promise of being something different.  Ira Sachs' Little Men is centered around the conflict between economics and humanity, telling the story of two young boys in Jake and Tony, who slowly see their friendship tested due to a financial conflict between their parents. The story begins in tragedy, with the death of Jake's grandfather, prompting Jake and his family to move back into their old Brooklyn home. This is where Jake befriends Tony, whose Chilean mother runs the shop downstairs, a space that was previously owned by Jake's grandmother. With gentrification grabbing hold of the neighborhood and Jake's parents struggling financially, a conflict emerges when Jake's father, Brian, asks Tony's mother to pay more in rent, something which she is reluctant to do herself, due to long history in the space, as well as her own financial burden. Ira Sachs' Little Men is a film that openly acknowledges the difficulty of the situation it documents, understanding that there is no easy answer to this perpetual conflict between finances and humanism. The film is well balanced in this regard, being fair in how it characterizes both sides of this disagreement, mainly due to two strong characterizations of both Tony's mother & Jake's father. Having a close relationship with Brian's deceased father, Tony's mother feels betrayed by the rent hike, as she laments how his father always viewed her as part of the neighborhood. Her perception is that Brian's father recognized the importance of community and relatioships over money, and the tragedy of her situation stems from her losing her shop, something which she has worked a long time to have in the Brooklyn neighborhood. On the otherhand, Brian is concerned by his own families current financial situation, being a character who is almost completely bankrolled by his wife, a psychotherapist. The film hints that his own masculine insecurities, struggling to provide as an Actor, may be the primary cause for his tough stance on Tony's mother, but given the fact that he is being pushed in that direction by his sister too, I'd argue his heart remains constantly in a state of conflict throughout the narrative. As Brian himself even laments, no one pays the same stagment rent forever, touching on the reality of the world we live in. While this conflict is quietly festering in the background, much of Little Men chronicles the budding friendship between Jake & Tony, two young men who are both interested in studying the arts, painting and acting respectively. As the two grow closer together, the parent's financial conflict begins to come more to the forefront of the story, like a dark cloud slowly looming over the healthy, growing friendship between these two young boys. When the parents scuffle, these boys are immediately torn apart from each other, as the business matter itself reflects poorly on the youthful innocence of these two characters, each of which is only concerned with the humanity of the situation they find themselves in. This is particularly a tragic series of events for Jacob, an introverted character who tends to have trouble keeping friends. That is one of the great tragedies of Little Men, with the financial security of his family directly restricting Jake's own ability to maintain his friendship, with both parents being responsible for letting their financial conflict interfere with the importance of their children's friendship. A film that is well balanced and doesn't pretend to have simple answers to a tough situation, Ira Sachs' Little Men reveals the harshness that can be associated with economics while never being simplistic or unfair in its story of how two parents' financial conflict slowly strains youthful companionship.  Daniel Burman's The Tenth Man is a story about the relationship between personal identity, community and tradition, following a character in Ariel who for a long time has struggled to embrace the Jewish community in which he was raised in Buenos Aires. After years away, Ariel receives a phone call from his father Usher, which prompts Ariel to return to Buenos Aires in an attempt to reconnect. The founder of a charity foundation in Once, the city's bustling Jewish district, Usher is extremely busy, and on Ariel's arrival, he finds himself getting entangled in his father's vast array of charitable commitments. In the process of trying to track down his father in person, Ariel meets Eva, an independent young woman who is a part of the Jewish community, someone who ultimately aids in helping Ariel come to grips with the traditions and the community that have unnecessarily divided Ariel and his father. Daniel Burman's The Tenth Man feels like a very personal story, a low-key effort focusing on a character in Ariel who never seemed to be able to find his place in this world. Much of his personal solitude stems from the perceived neglect of his father, a man in Usher who is extremely dedicated to serving his community. This has led Ariel to somewhat resent the Jewish community and their traditions, a man who left Buenos Aires in an effort to escape this perceived slight, one in which he saw his father focusing on the community more than his own son. It's only through Ariel's interactions with Eva that he begins to become comfortable in his own skin, understanding the notion that he can maintain his independence and singular voice while still embracing the community. The Tenth Man is a film that spells very little out for the viewer early on, a lowkey film that relies on setting and character to define its story. The film's message is simple yet borders on heavy-handed at times, with much of the first half revolving around Ariel's frustrations related to the countless tasks his father asks him to carry out for the community. The whole experience of Daneil Burman's The Tenth Man feels deeply personal but also slight, and I'd be lying if I didn't find the pacing of this film severely lacking at times. The whole story, centered around Ariel's angst towards the Jewish community due to his father's neglect, comes relatively into focus early on, and while I'm always a fan of minimalist work, The Tenth Man simply wasn't meditative or contemplative enough to keep me engaged. Ultimately about a character finding himself and being comfortable where he came from, Daniel Burman's The Tenth Man has an important message but unfortunately doesn't show the nuance in execution to be anything particularly special. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed