Joachim Trier's Louder Than Bombs is an emotionally raw study of one families attempt to overcome tragedy, their struggle with grief, and how during times of great emotional stress, clear communication and expressing personal sentiment can become increasingly difficult. Focusing on the lives of a father and his two sons as they grapple with the untimely death of their respective mother/wife Isabelle, a noted war photographer, Louder Than Bombs is an uneven exploration of grief, using these three characters, each of which still grapple with Isabelle's death, to express the importance of communication and the severe pain that comes with letting go/moving on. Since Isabelle's death, Gene, the patriarch of the household, has been struggling to maintain a consistent relationship with his youngest teenage son Conrad, who is constantly in introspection, hiding in his video games and personal solitude as he attempts to make sense of the loss of his mother. Jonah, the eldest son, has just arrived to the family home, taking a leave from married life and academia to help organize his mother's archive of photography, which soon will the presented at a New York exhibition honoring his mother's work. Featuring Joachim Trier's sharp narrative focus, Louder Than Bombs is a fascinating, albeit flawed film, which effortlessly blends past and present, as it attempts to piece together the struggles of these three characters, each of which has failed to express their personal pain from Isabel's loss in any constructive light. Louder Than Bombs stresses the importance of fully-developed characterizations over narrative pacing, with Trier being a filmmaker that understands the importance of letting his characters shape the story, not vice versa. The screenplay seamlessly shifts from perspective to perspective, attempting to unveil how grief and loss have effected the psyches of its three main characters, each of which struggles to deal with and express their emotions. There is a lot to like in Louder Than Bombs as the film offers lots of fascinating insights about grief, communication, love and loss, as well as some powerful and transfixing meditative moments, but i'd argue that some of the film feels painfully overly dramatized, specifically the plight of Conrad, the youngest son who struggles mightily to make sense of his mother's death. Conrad is a character in a lot of pain but while the film surely expresses the confusion and unique perspective of this loner character, his actions at times feel forced, particularly in his actions towards his father. I'd argue that Conrad's emotional outbursts and general angst are actions that more aid the characterization of Gene, his father, a character who struggles to share the truth about Isabelle's death with his youngest son. Gene's lack of communication, his inability to express these details and talk about his emotions with his son lead to Conrad's behavior, but the way Conrad behaves seem to serve the characterization of Gene's guilt and perceived failure as a father and husband more than his own internal struggle, making this young boy a character that is hard to be empathetic towards due to his angst never being meticulously defined outside of the obvious. Louder than Bombs attempts to make a connection between Conrad's internal issues and the deep-seeded fragmentation of family but it simply doesn't always work, as the character comes off a little too much like an impudent child, and not enough like a child struggling to deal with his mother's death. I'd actually argue that one of the best characterizations of the entire film is Isabel, a character who shapes much of the story due to her death, but who also shapes the thematic lynchpins of the film, being a character who herself struggled to communicate with her husband. Isabel is a character stuck between two worlds, her personal life back in the states and her life as a war photographer. She is a character who suffers from a feeling of detachment from her family due to her profession, which sees her traveling all over the world in an effort to document conflict. The emotional effect of her profession, the toll it takes, is what leaves Isabelle struggling to express herself to Gene, a lack of communication that plagues this family even after her death. One of the more interesting aspects of Louder Than Bombs is how it captures the profound and powerful effect of death, not only in it study of these three family members but also in Isabelle, whose psyche becomes increasingly unstable and fractured due to the weight of death and conflict she saw through her profession. The film almost seems to capture the trickle-down effect such depression and despair can have, as Isabelle took her own life due to the pain that in turn led to more pain for Gene, Noah, and Conrad. Due to well-crafted filmmaking and a compelling narrative that seamlessly shifts between perspectives of its characters, Joachim Trier's Louder Than Bombs is a film that despite its flaws is always fascinating, touching on the importance of communication but also the importance of pushing on through times of grief and despair, soldiering forward so to speak, and not letting loss and the darker aspects of this world consume you.

0 Comments

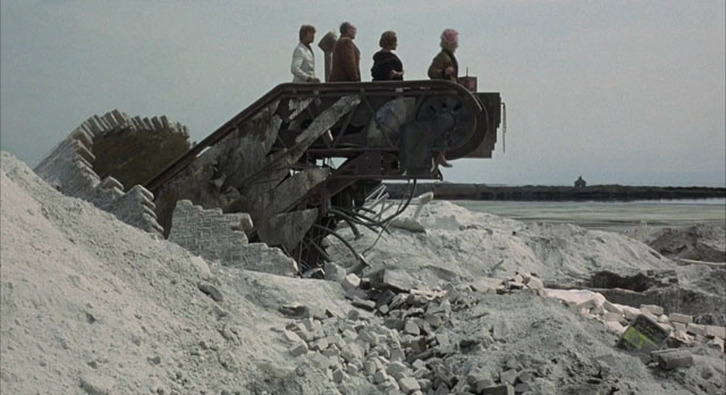

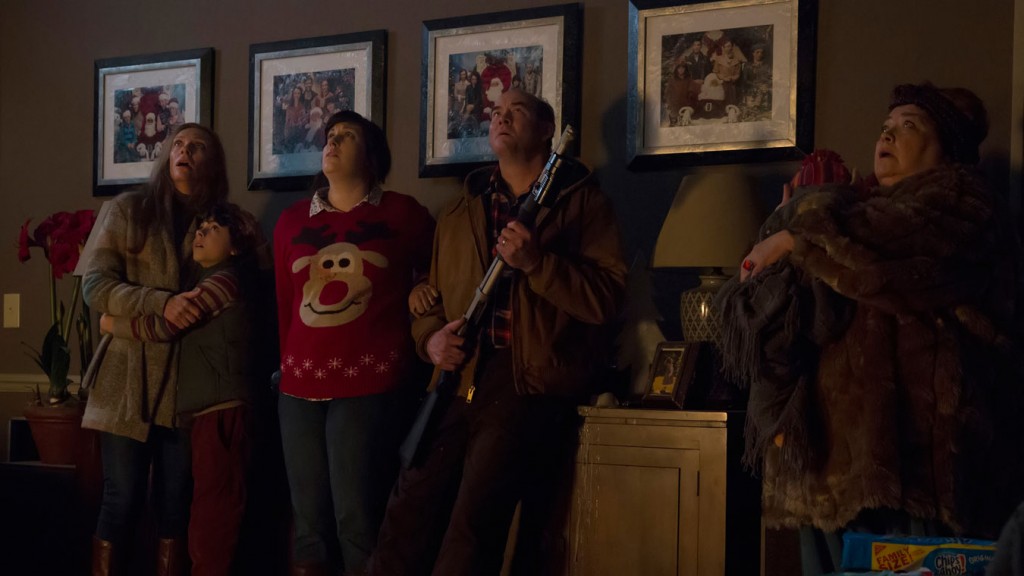

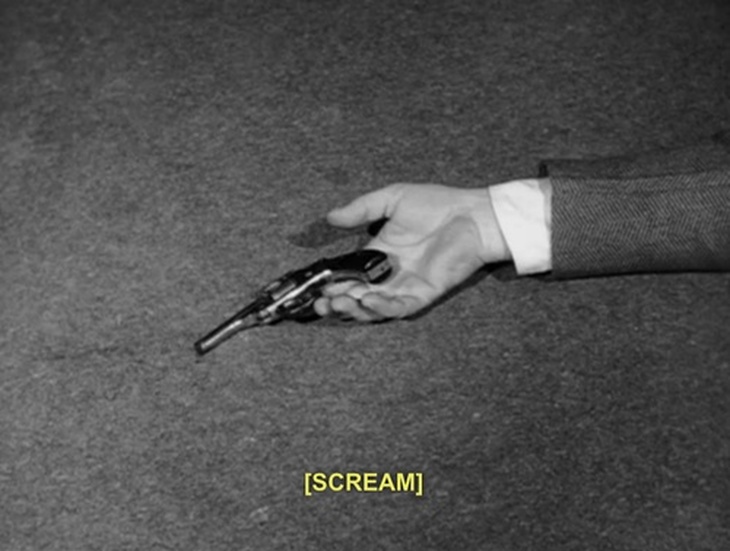

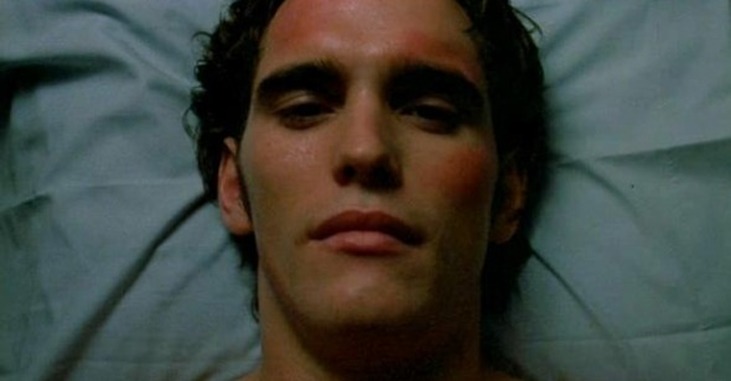

Without question Richard Lester's most bizarre film I've seen to-date, The Bed-Sitting Room is a manic, absurdest black comedy which takes place in post-apocalyptic England, following the remaining survivors as they attempt to carry-on their everyday lives. Richard Lester's The Bed-Sitting Room is a comedy with very British sensibilities, sharing a lot in common with the work of Monty Python as it relies on absurdest and slap-stick humor to satirize aspects of society. Focusing on the fears on nuclear war sweeping England at the time, The Bed-Sitting Room imagines the world after a 2 1/2 minute holocaust has wiped out most of the country, documenting a slew of characters who attempt to go about their lives in a very similar way to before, regardless of the social structures of society being completely eviscerated by the nuclear holocaust. Long used to the institutions of modern society, Lester's film finds its characters become the institutions themselves, comically and ignorantly pretending to hold on to the same way of life in this barren landscape. One man who travels door to door, putting his head inside TV sets to broadcast the news is the BBC, another man provides all the electricity for the nation via bicycle, while the National Health Service is one simple doctor. Through quite comedic circumstance and absurdity, The Bed-Sitting Room seems to have something to say about mankind's reliance on the institutions of society and their need to carry on traditions, with much of the best comedic gags in the film being focused around the juxtaposition of British's mannered, elegant way of life with the brutal, tragic circumstances of these characters' living in a post apocalyptic society. The emotional core of the film, centered around two young lovers doesn't quite work, but their desire to participate in the traditions of domesticated life, such as marriage and children, certainly once again speaks to humanities' desire to hold on to tradition. If you remove all the absurdism, which mind you is easier said than done with this film, The Bed-Sitting Room is a rather dark narrative, focusing on the death a nuclear holocaust would bring, the radiation and potential mutation it could cause among survivors, and the general wickedness of the barren landscape. It's through Richard Lester's satirical and absurdest lens that he has managed to create a film that both warns about the perils of Nuclear War but also pokes fun as the fear which society has for these weapons of mass destruction. Featuring beautiful, surrealist production design, Richard Lester's The Bed-Sitting Room is a one-of-a-kind satire of the nuclear holocaust, being a film with a meandering narrative that cares more about satirical absurdest comedy and its thematic ideals centered around institutionalization and tradition, more so than narrative lynchpins.  Michael Dougherty's Krampus is a pleasantly surprising horror comedy that is very much in the same vein as iconic films of the 1980s such as Gremlins, due to its ability to balance both its horror and comedy elements to great effect. A horror film centered around the Christmas holiday, Krampus brings a gleefully cynical perspective to the season of giving, focusing on the selfishness and individualism of its characters, who have essentially forgotten the whole purpose of the holiday. Featuring a memorable opening sequence in which the film skewers the consumerist culture that has come to define Christmas, Krampus beautifully sets the stage for its antagonist, an evil spirit who punishes those individuals who themselves have lost hope in the Holidays, those who simply have forgotten to be thankful for what they have. Centered around a dysfunctional family, Krampus' narrative is set in motion when Max, the youngest child of the household, turns his back on Christmas, turning cynical towards the purpose of the holiday after things don't go his way both at school and at home. This lack of festive spirit unleashes the spirit of Krampus on Max and his family, who are forced to bunker themselves up in their home as they attempt to survive the night. Michael Doughterty's Krampus is a fun and inventive horror comedy which takes many of the beloved holiday icons of Christmas and turns them sinister, providing a sometimes scary, often memorable experience. Krampus features far more "world-building" than I expected, featuring a host of fun monstrosities and creative Christmas' themed atmosphere that shows off the filmmakers ingenuity, while relying on practical effects more so than not to create its horrific environment. The film's tone is playful and self-aware, understanding the inherent silliness in its storyline that features psychotic, killer gingerbread-men, managing to balance the line between self-awareness while never abandoning the overall sense of danger and horror facing its characters. From Max's loud and obnoxious in-laws who feel like exaggerated caricatures, to the film's use of cartoonish sound cues, Krampus is more fun than scary, though I'd still argue the horror itself is effective, thanks largely to the filmmaker's creative mindset. From a pure horror standpoint, Michael Dougherty's Krampus may disappoint some of its more horror-thirsty filmgoers but when considering the films overall intentions are more centered in comedy AND horror, Krampus is a worthy experience and memorable throwback to 80s Horror-Comedies which managed to blend the two so effectively.  Edgar G. Ulmer's Ruthless is a healthy slice of American Gothic, telling the rise and fall of wall street financier Horace Vendig, a man who rolled over anyone who stood in his way, including his lifelong friend Vic Lambdin, to accrue his considerable wealth. Told almost entirely in flashback, Ruthless is a film which attempts to comprehend how a man like Horace could become so rotten, examining his quaint upbringing and early relationships, offering up insights into what motivated Horace from an early age to be successful at any cost. The characterization of Horace is what makes Ruthless such a compelling experience, with Zachary Scott making this despicable character somewhat likeable, or at least empathetic, as the story documents this character's struggles at an early age to feel successful and desired. Through the flashbacks to Horace's youth, Ruthless paints a portrait of a character who always viewed money as the ultimate symbol of success, being the lone son in a fractured household with little confidence, little money, and even less assurance from his divorced parents. Ruthless expresses how this environment breeds in Horace a character who always needs to prove himself, with these insecurities being the first step towards his detachment from nearly anyone who stands in his way. It's his ambition to accrue wealth and be successful, unlike his deadbeat father, with his formative years being the kindling which created this monster of a man who only looks out for his own personal gains. At its heart, American Gothic very much an angry film that raises questions about the darker aspects of the American Dream and capitalism in general, examining how the insatiable desire for success and greed are merely a bi-product of capitalist culture, with Horace pushing his own morality aside for the sake of the all mighty dollar. Whether it be an old friend such as Vic, or a business partner who helped him in the past, Horace's short-term memory when it comes to gratitude or empathy perfectly encapsulates the Wall Street mindset, where nothing else matters when compared to dollars and cents. Through the film's desire to understand Horace's formative years, Ruthless earns much of its commentary on the insatiable qualities of greed when money is what defines success, manging to never feel too heavy-handed thanks to a full-bodied characterization. Featuring black and white cinematography that gives the film a gothic look and feel, Edgar Ulmer's Ruthless is an engaging Eagle-Lion story that earns many of its ideals thanks to strong performances and a sharp screenplay.  A German-produced film directed with bravado by American filmmaker Samuel Fuller, Dead Pigeon On Beethoven Street is a rather generic hard-boiled private eye story, centered around an international extortion ring, whose been targeting high ranking political officials. Sandy is the American Private Eye who arrives in Germany seeking revenge for the death of his friend who is believed to be shot dead by this international extortion gang. Infiltrating the crime ring himself, Sandy joins forces with one of the gang's seductive agents of extortion, hoping to discover the man at the top of this criminal organization and bring him to justice. Certainly one of the more boldly directed television movies I've seen, Samuel Fuller's Dead Pigeon On Beethoven Street finds the hard-boiled filmmaker bringing his bold style to the small-time production, using fast twitch editing, slow pans and scans, and impressionistic cinematography that bring this otherwise dull story to vivid life. While watching this film I couldn't help but think about some of Seijun Suzuki's work with Nikkatsu studio, as Dead Pigeon On Beethoven Street is a great example of how much creative direction and ingenuity can elevate source material. Fuller directs this story with such fervor, and while there really are very few action sequences, when they do come they don't disappoint, as Fuller uses his directorial craft to create a few memorably action sequences that pump with a visceral energy in every frame. The main protagonist Sandy is a staple of machismo, a character who expresses genuine glee when stumbling across Rio Bravo playing in a movie theater while tracking his latest assignment, a no-nonsense individual who is a specialist in violence. There is a fragility to this character though, a fish-out-of-water in Germany, with Samuel Fuller examining the existentialism, capturing how he lets his guard down due to this fragility, being a character who is attempting to make sense of everything around him in a foreign land. Being such an expressive film visually, Dead Pigeon On Beethoven Street is one of Samuel Fuller's more interesting efforts, almost as if the filmmaker took the gig just as an opportunity to boldly play with style, with the film offering up some truly ingenious cinematic tricks, as well as some great examples of the economics of filmmaking, as the director routinely does/tells a lot, doing very little.  While Matt Soble's Take Me To The River may be vague to a fault, it's never not engrossing, thanks to a unique narrative that pulsates with mystery and intrigue. The story is centered around Ryder, a gay California teenager, who isn't exactly thrilled to be visiting his Nebraskan relatives for a family reunion, a conservative, rural family whose ideals certaily seem backwards to the young man. In the opening scene of Take Me To The River, Ryder makes it very clear he'd rather just come out as soon as possible, not wanting to lie about who he is to his relatives, regardless of their feelings on the matter. For the sake of his mother though Ryder chooses to keep quiet about his sexual orientation, though some of his clothing, including bright red short-shorts, certainly draw the eye of his conservative, country relatives. Early on in Take Me To The River the filmmaker makes an effort to document the contrast of feminine and masculine roles in this rural culture, exhibiting how they are clearly defined. Ryder seems to only get along with his young, female cousins, especially Molly, who becomes quite attached to her older cousin from California. One day a strange encounter occurs away from the families watchful eyes, raising suspicion of Ryder when Molly returns home with blood in her crotchel region. While the negative minded ignorance around homosexuality is certainly documented, what transpires from there on out in Take Me The River is more about family secrets and the Ryder's mother's inability to stand up for her independence due to being constantly in need of her families' blessing. The mother is quietly a very fragile character in this film, needing to feel re assimilated into her family, needing to bond with them, even at times doing things at the cost of her son's psyche to do so. Ryder is simply a character who doesn't want to be there, now struggling to grasp why his uncle and Molly's father, Keith, became enraged at him and why he would jump to the worst possible conclusion. What eventually becomes clear is that Ryder has essentially become a pawn in the underlying emotional tug of war between his mother, Cindy, and her brother, Keith, though the film never makes it entirely clear what happened many years ago to begin this game of psychological abuse, if anything did at all. One of the best scenes of film is when Ryder is at Keith's house for dinner, featuring a great use of mise-en-scene that aids in creating a quiet, startling tension as Keith quietly dishes out psychological abuse. A promising debut feature, Take Me To The River is a film that is vague enough to conjure up various interpretations into what exactly happened in the mother's past, as well as how far Keith's demented nature runs, but the film's craft is undeniable regardless of your feelings on ambiguity.  Robert Budreau's Born to Be Blue is a creative re-imagining of jazz trumpeter Chet Baker's life in the 1960s, documenting his attempts to rejuvenate his career after a visit from his past. While starring in a film about himself, Chet enters into a romance with his co-star Jane who happens to be portraying Chet's ex-wife. Production is halted after Chet is assaulted by drug dealers who he still owes a debt to, leaving Chet's face badly damaged and his musical career in question because of it. While Chet's crippling drug addiction is where he would usually find solace, Jane's affection and support instill Chet with enough confidence to remain clean as he attempts to learn how to play Trumpet again. Born to be Blue could certainly be described first and foremost as a vehicle for Ethan Hawke, who as Chet Baker delivers one of the best performances of his career. Hawk exhibits the instability and fragility of this troubled Jazz musician with nuance and grace, creating an empathetic character out of an overall self-absorbed man, who finds his sole meaning in life, playing jazz trumpet, taken from him overnight. Chet is a character who lost his identity overnight, and much or the heart of the film is about him attempting to get it back in the form of musical acknowledgement, with Jane being the stabalizing force that keeps him clean. The film is as much about Chet's struggles with addiction as it's about his physical rehabilitation, as Born to be Blue captures in Chet a man whose insecurities fueled his need for heroin. From regionality, being a West Coast musician in an East Coast jazz world, to having the wrong complexion, being a Caucasian in the traditionally African American Jazz scene, Born to be Bad argues that these insecurities fueled his need for drugs, as Chet was a character who became dependent on the calming presence of the high, offering up temporary reprieve from his pain and insecurity about fitting in and being acknowledged. Like the emotions of Jazz themself, Born to be Blue ends in a tragic way, with Chet once again succumbing to the calming presence of heroin before a very important show, a decision that relaunches his career after a phenomenal performance but also shatters his marriage to Jane in the process, as she is a woman who refuses to be by the side of a heroin addict. Born to Be Bad is about the insecurities of being an artist, the importance of having support, and the devastating grip of drug addiction, combining to deliver a compelling and unique biography style film that wisely focuses on one era of its subjects life, and in doing so, creates a characterization that fully encapsulates the type of man he was.  Prompting fond memories of the sensory experience that was Lucien Sastaing-Tyalor & Verena Paravel's Leviathan, Mauro Herce's Dead Slow Ahead is a startling, impressionistic documentary thats observant eye tells a dark story of isolation on board an ocean freighter that goes by the name the Fair Lady. With very little dialogue, Dead Slow Ahead relies completely on its visuals to tell the story of life at sea, delivering a haunting experience that at times stands up to the imagery one would find in any good horror film Dead Slow Ahead transports the viewer completely into this cold, isolated, machinery infested environment, documenting the setting at all times with an impressionistic lens. Dead Slow Ahead is a beautifully photographed film, and I don't just mean in terms of startling imagery, as every frame of this film helps tell the story of this dark, oceanic voyage. Dead Stow Ahead tells a story of utter isolation, with wide compositions that beautifully express the mammoth size of the sea, and the vast sky above, evoking a sense of emptiness on the horizon, a voyage to nowhere for this crew of isolated men, so to speak. Even in the few scenes where the ship does reach landfall, Dead Slow Ahead visually presents the coast as a hazy, foggy, distant location, detached from the ship and the crew on the Fair Lady. The atmosphere of Dead Slow Ahead can be downright nightmarish, presenting the crew as pawns, slaves to the Fair Lady's vast, cold steel. The various creeks of the ship are incessant and exhausting, almost as if the Fair Lady is a mythical creature that the crew serves. What I found so striking about Dead Slow Ahead is how the ship is a character itself, a vessel that has authority over the crew, those that slave away at various machinery to keep operations going. Dead Slow Ahead is very impersonal to the crew through most of the film, almost as if to suggest they merely a part of the ship which they serve. It's only towards the end that that film that it provides more intimacy towards the crew of the ship, though it still evokes a sense that they are at the mercy of this behemoth, steel-made vessel. One sequence towards the end of the film that really stood out involves various crew members calling home. This sequences beautifully expresses the totalitarian control the ship has over the crew, with the filmmakers using a camera that wonders through the machine rooms of the Fair lady, documenting the the tight corridors of the vessel, exploring the steel pipes and dark crevices full of machinery, defining these characters by the environment they inhabit. While the camera wonders, the dialogue of various crew members on the phone provides emotional weight, only strengthening the isolation evoked earlier on a humanistic level. A brooding exploration of isolation at sea, Dead Slow Ahead captures the vastness of the ocean and the harsh conditions of labor in an impressionistic way that should not be missed.  One of most anticipated movies of the year (I think?), Zac Snyder's Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice picks up after Man of Steel, where Superman has quickly become one of the most controversial figures in the world due to his god-like strength and seemingly infinite power. While many view him as a symbol of hope, a growing minority view this caped figure as a threat to humanity, including Bruce Wayne aka Batman, who views Superman's god-like power as a danger and imminent threat to mankind. While Batman and Superman circle each other, and the world questions exactly what type of hero they need, Lex Luthor lurks on the sidelines, concocting a sinister plan which leads to the creation of Doomsday, a creature even more powerful than Superman. While I won't go into much detail about the plot points of Superman v. Batman, Zac Snyder's latest stylistic opus is the bombastic, painfully serious, overly-brooding experience I was expecting. The narrative itself isn't out of the norm for these types of superhero films, with many of the major story beats slowly crawling towards the two inevitable action scenes everyone is here for - Batman vs. Superman and the Doomsday finale. That being said, Batman v Superman's plotting is efficient enough, being really a dual narrative between Batman and Superman which at times can feel incoherent, but considering the amount of characters, the script actually does a respectively good job of not feeling overstuffed. While the narrative and story are certainly dense and a tad illogical, I'm not even going to spend the energy talking about the painful flashbacks and dream sequences throughout, Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice's big problem is its characterizations, which by-and-large are humorless, cynical, and at times cringe worthy. Think of it as a super-serious ying to Batman and Robin's yang, offering up an almost direct inverse to the Schumacher's overly playful, consumerist kaleidoscope of bright neon lights. Intentional or not, Batman and Superman are borderline psychopathic and sociopathic characters respectively in this film, with Batman being driven by vengeance and hate, while Superman shows very little empathy throughout the film, almost as if he is saving many of these people simply out of boredom. In an attempt to be fair, some of the problems with Superman may be due to the stoic acting of Henry Cavill, but with Batman in particular, it's hard to even view the character as a "hero" of any sorts. Within these characterizations is where Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice becomes its most interesting though, as both these superheros are predicated out of fear or revenge. One could argue that the film has allegorical intentions about the state of American, and the world in the post 9-11 environment, and while I certainly wouldn't call it an intentional commentary, the overwhelming cynicism and borderline fatalism that envelopes this entire film left me keep going back to this ideal. Batman v Superman is a film that routinely hits the viewer over the head with a cynical viewpoint of the current state of American society, personifying the fear associated with the war on terror, the desire to control and enforce everyone and everything, and the disconnected selfishness of society. Holly Hunter's senator character represents the incessant desire of America to police and control the world through her desire to control Superman, while Lawrence Fishburne at one point rides Clark Kent for wanting to report on the Batman, lamenting "its not the 1920s anymore, no one cares", a very cynical viewpoint that asserts the ideal that people simply aren't interesting in anything that doesn't effect them, as they'd rather be entertained or distracted by entertainment such as sports. Considering Batman being a character who never uses firearms, I also found Batman's excessive use of guns through the film fascinating, as if the filmmakers were making a commentary on America's obsession with guns, using this American icon to make a point. While I'm sure many of these observations are completely coincidence, I'd argue Batman v Superman, unintentionally or not, paints a rather vivid and startling viewpoint of the world where cynicism and fear have breeded 'heroes' who act more out of fear and revenge than kindness or bravery, something we as a society may deserve. In a way, Batman v. Superman is the Ying to Batman and Robin's Yang, a brooding, dark experience that never manages to say much Zac Snyder's Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice is a mildly entertaining superhero film which probably will appeal to most fans of the comic book genre, but where the film is most interesting is its most likely unintentional thematic ideals, being a cynical, brooding film that questions if these characters, with all their flaws, are simply what we as a society deserve.  While not wholly-original by any means, Gus Van Sant's Drugstore Cowboy is a pensive, unbiased examination of American Drug Culture which is never judgmental nor romanticized, being a film that is simply interested in documenting the transient lifestyle of those individuals who live a life of very little foresight. The film itself focuses around Bob, the leader of a group of dopeheads who wander somewhat aimlessly around the country robbing pharmacies to feed their addiction. Bob is accompanied by his old friend Rick, his wife, Dianne, and a teenage junkie, Nadine, and the foursome spends every waking moment either getting high or planning out where to get their next fix. When one of the addicts of their group dies unexpectedly from an overdose, it prompts Bob to attempt to go straight, a task which is much easier said than done for a character whose only real relationship includes a wife in Dianne who is determined to stay high. Drugstore Cowboy is a film intent on transporting the viewer into the transient world of its characters, examining the fatalistic mindset of this culture which lives in the moment, only interested in finding their next inebriated state. Using lots of close-ups, punch-ins, and surrealistic touches, Van Sant has crafted a film that beautifully exhibits the mindset of a drug-addict, expressing the the euphoria and tranquility inebriation brings to those with little direction. The film is honest in its portrayal of the euphoria which psychedelic drugs can bring but also the dangers of such actions, most notably in how Drugstore Cowboy exhibits the instability which addiction can bring. In Drugstore Cowboy every relationship feels secondary to their addiction, with Bob for example being a character who is quietly threatening as the leader of this group of pharmaceutical robbers, calm unless someone questions his authority in the gang or simply gets in the way of his drug use. The film exhibits the raw power of drug addiction, the paranoia it causes in the psyche where nothing is more important than seeking out that next euphoric high. Drugstore Cowboy is far from a political film, nor one interested in simply being a cautionary tale, but instead a film that attempts to comprehend the culture of those individuals who have reached a fatalistic point in their lives, uninterested in everyday life, with drugs being the only thing that offers them relief from society. The fringe of society is captured vividly and in-detail with Van Sant's use of composition and surrealism, evoking a feeling of borderline hopelessness in this sub-culture, people with little motivation to contribute to a society they can't comprehend. When Bob attempts to go clean towards the back half of the film is when Drugstore Cowboy socio-political message becomes more clear, being a film that focuses less on condoning those with this crippling addiction and more interested in the reflection this sub-culture has on America as a whole. Transporting the viewer deep into this shabby, transient culture where uncertainty reigns, Drugstore Cowboy provides one of the more honest portraits of Drug Culture, never condoning it nor romanticizing addiction, intent only on providing a realistic portrait of the fatalism, spontaneity, despondency, pleasure, and dependency which the culture breeds. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed