Todd Strauss-Schulson's The Final Girls is a satirically take on the slasher genre that is certainly clever, but unfortunately it lacks the bite necessary to stand out in the ever increasing field of satirical, horror comedy films. The story is centered around Max, a teenager who hasn't quite been the same since the death of her mother via car crash several years ago. Reluctantly, Max and her friends attend a tribute screening of the infamous 80s slasher film starring Max's own late mother, but when the movie theater catches on fire, Max and her friends find themselves inexplicably sucked into the very movie they were watching. Trapped inside the cult classic b-movie slasher, Max and her friends must team up with the fictional characters at "Camp Bloodbath" in an attempt to kill the machete-wielding killer, Billy Murphy. While The Final Girls is a clever concept that certainly understands the tropes of the genre, the film never really embraces what it is trying to create, offering up a soft-serve PG-13 film that never has the bite necessary to fully satirize the genre. The film's best attribute though is definitely is ingenuity when it comes to mocking the genre tropes, offering up a surprisingly smart lecture of sorts on the rampant sexism in these types of films which is pointed and quite funny. I particularly liked the clever way the film satirizes the flashbacks, doing so in a unique way, though I'd still argue that most of the film's smartest ideas aren't specific to the horror genre (end credits, sequels, flashbacks, off voice narration). Its not that The Finals Girls is bad by any means, it just doesn't bring that much new to the table, offering up more of the same we've seen before from these types of films. The dramatic weight of the film, centered around Max and the death of her mother, almost feels out of place at times as well, and while I wouldn't say it doesn't work I'd certainly argue it's unnecessary to the story. While one could certainly argue that the R rating isn't necessary, The Finals Girls really struggled due to its inability to satirize the bloodshed of the slasher genre, being a clever, playful film that never has the bite I was hoping for.

0 Comments

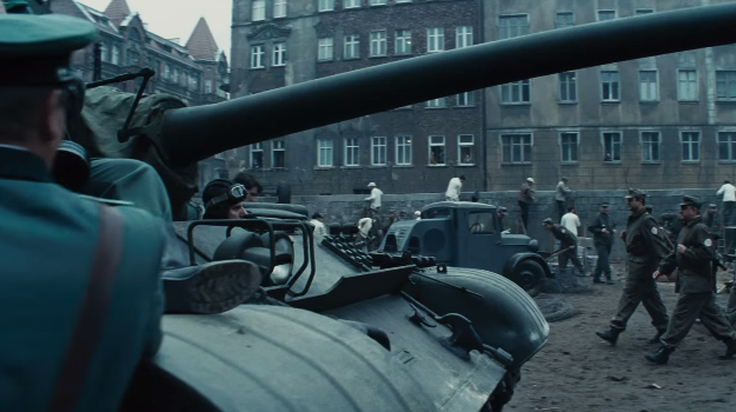

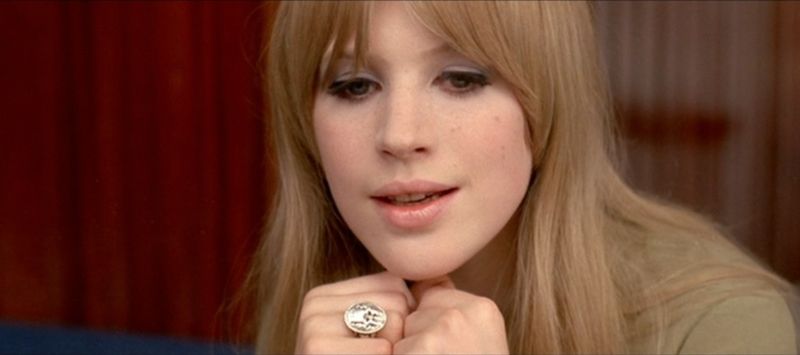

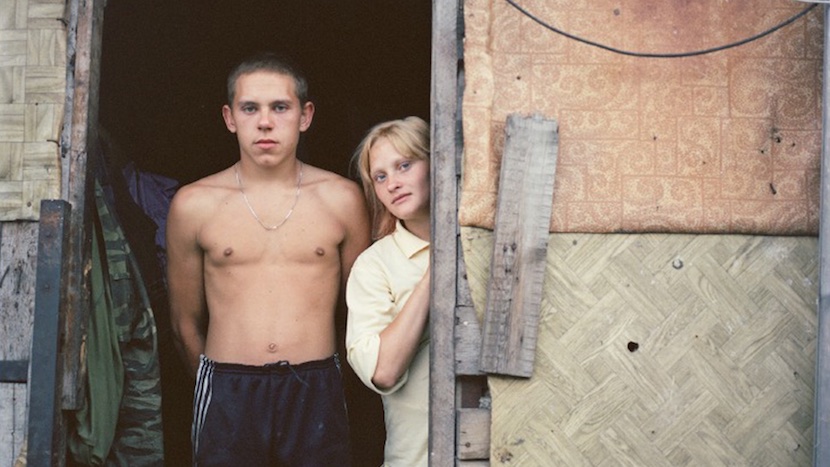

Once regarded as "the world's greatest film editor, Rey Cisco now has to resort to cutting low-budget trash cinema due to a horrific accident that left him with a wooden right hand. While working on his latest picture, the lead actors of the film begin to be murdered off one-by-one, prompting an investigation into who could be behind the gruesome deaths. Peter, the chief detective on the case, suspects Rey may be responsible, but as he digs deeper into the mystery he discovers something far more sinister, and supernatural is lurking behind the scenes. Adam Brooks & Matthew Kennedy's The Editor is an absurdest giallo-type horror film which manages to be both an homage and a satire of the Italian Giallo genre. While I can't put the film up there in the same realm as something like Black Dynamite, it's hard not to at least argue that The Editor matches that film's creativity and detail, delivering a spoof of a genre which only fans of the genre itself could provide. From the badly dubbed English to the ridiculously convoluted plot, The Editor really captures many of the traits of the Giallo genre to perfection, offering up some impressive comedic moments centered around the gratuitous nudity, violence, out of nowhere introspection, and over-the-top color palette that are common in the subgenre. With plenty of poor taste humor, particularly centered around Rey's crippled hand and the overbearing misogyny that runs rampant throughout the film's running time, The Editor is clearly a film that doesn't take itself seriously, being a very playful horror comedy that works far more than it doesn't. While Rey is the main protagonist, I particularly loved Peter, the detective on the case, who provides some of the funniest moments of the film. Being a man who is described as having "intense passion", The Editor provides the viewer with two highly memorable sex scenes with Peter, sequences that had me in uproariously laughter for the ingenuity and absurdity. While viewers unfamiliar with the Giallo genre may just find The Editor confusing and "dumb", this is a film I would highly recommend to anyone who is a fan of the genre, providing a satirical homage to the bold, bizarre horror subgenre which I personally love.  Taking place in the middle of the cold war, Steven Spielberg's Bridge of Spies tells the incredible true story of James B. Donovan, an insurance lawyer, who finds himself recruited by the CIA to help with intense negotiations over the exchange and release of Francis G. Powers, a CIA U-2 pilot who was arrested in Russia, and Rudolf Abel, a KGB intelligence officer, who was arrested in the United States for espionage. Let me start off by saying that I'm not much of a fan of Steven Spielberg as a dramatic filmmaker, much preferring his more escapist type entertainment films such as Jaws, Duel, and Raiders of the Lost Ark. That being said, Bridge of Spies surprised me quite a bit, being one of Spielberg's most impressive films from a thematic standpoint. The film begins with a rather elaborate spy sequence, which finds the CIA arresting Rudolf Abel in New York City. It's an enticing and enthralling sequence, but what makes it so important is that it reveals that Rudolf Abel is in fact a soviet spy, letting the audience in on something that is somewhat ambiguous to our main character, James B. Donovan, as well as everyone else. Why this is important is that Spielberg is essentially acknowledging early on that it doesn't matter that this man is a Russian spy, with Spielberg's thematic intentions set on capturing the danger associated with unbridled patriotism and ones blind allegiance to a country over humanity. Through this incredible story, Spielberg's film captures how governments use people as vessels, dictated by overarching beliefs of power and security which essentially make us all pawns. While probably not as biting a criticism as I'm making it out to be, Bridge of Spies certainly raises interesting questions about how the allegiances we have towards our countries can outpace our allegiances to humanity. Given the setting, Bridge of Spies is a film that effectively captures the hysteria during the cold war, showing the power of fear used by both the United States and Russia, which led to the United States going against its own ideals, such as due process and individual rights, hiding behind the vail of security in an attempt to win. The film shows how quickly the fundamentals in which a nation are built can be deteriorated in times of conflict, with much of the film's heart centered around James B Donovan's character being the lone man who stands up for the rights of Rudolf Abel. Spielberg will continue to be Spielberg in some regards, and Bridge of Spies still suffers from a few emotionally manipulative sequences, but what bothers me even more is his continued lack of nuance and subtlety at times, as if he never trusts the audience to be smart enough to put things together by themselves. While I wouldn't say Tom Hanks performance is particularly impressive, he really is perfect in this role, bringing a great sense of uneasy tension and subtle comedy to the role of a lawyer who finds himself in the middle of a major international incident during the Cold War. Far from perfect, Bridge of Spies is a film of Spielbergs which I simply cannot help but praise, being a film that sees the filmmaker speak on a more intellectual level than is typical for his efforts.  Personally, Hollywood's obsession with the biopic drives me crazy, due mainly to the large majority of them being very by-the-numbers, as well as having a very skewed perspective that only seems to focus on the positives and not paint a vivid portrait of a true human-being. We all have flaws, and fortunately with Steve Jobs, the film doesn't make these same mistakes, being a vivid portrait of an innovative man told in a rather unique way. As one would expect from any film from Aaron Sorkin, Steve Jobs is a very sharp, lively script which does a magnificent job of capturing the heart and soul of a man who was consumed by his passion for innovation. I particularly loved how the primary structure of the film is set across the various launches of Steve Jobs' latest products, an ingenious device that not only creates a unique narrative structure, but more importantly this decision perfectly encapsulates its subject, a man in Steve Jobs who is defined by his products and judges his success as a human-being entirely by the success of his various innovations. The performances in Steve Jobs are all top notch, particularly Michael Fassbender, who does an incredibly job at capturing the nuance of a man in Steve Jobs who is a good soul, but overly demanding of everyone around him, pushing people away and alienating his loved ones in his pursuit of perfection. I liked that the film captures how Jobs was not a creator but a genius marketer and innovator, with one of my favorite scenes of the entire film being a heated exchange towards the end between Jobs and Steve Wozniak (Seth Rogen), one of chief coder/engineers responsible for creating many of the products Jobs envisioned. The heart and soul of the film is centered around Jobs relationship with his daughter Lisa, a young woman who Jobs essentially denied was his daughter for years when she was young, only to further alienate her due to his obsession with innovation. While these paternal dynamics do deliver some powerful sequences throughout, thanks largely to Fassbender's acting and Sorkin's dialogue, Steve Jobs completely crumbles in its final minutes, with one of the most forced, mind-numbing endings I've seen in awhile. It doesn't even feel like the same film, and without going into details, the last few minutes of the film essentially betrays everything before it, with Boyle's direction being laughably manipulative and corny in a way that would make the Hallmark channel blush. Overall, Boyle's direction in general is somewhat hit-or-miss, injecting the film with a great sense of style and unique ideas which at times provide expressive, visual storytelling, while other times these decisions unfortunately are all flash and little substance. While the film has its issues, Steve Jobs is a very solid biopic about an innovative man, but perhaps the film's most interesting aspect is how it captures the arrogance often times associated with success, capturing the alienation and even cruelty towards others it often breeds.  Chad Gracia's The Russian Woodpecker is a fascinating and important documentary chronicling eccentric artist, Fedor Alexandorich, a Ukranian man who was one of the millions of victims of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Investigating the mystery behind the disaster, Fedor begins to uncover a damning Cold War-era Soviet secret, one that feels even more relevant with the Ukrainian uprising taking place in Kiev. The Russian Woodpecker is a strange documentary which seems to be unclear as to what it intends, beginning simply as a document of a idiosyncratic, but brilliant artist only to transform into a powerful portrait of modern day Russia/Soviet Union, where intimidation, fear, and threats of violence are commonplace. The film's structure is quite idiosyncratic, much like its protagonist, but what Chad Gracia has created with The Russian Woodpecker is a truly unique account of the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown while simultaneously delivering a powerful biographical film of a man who eventually comes face-to-face with the oppressive forces of Russia. Perhaps the greatest aspect of The Russian Woodpecker is how it documents fear and oppression, with the film becoming downright frightening in its back-half after Fedor discovers what he believes is the true cause of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. The film documents how Fedor himself becomes intimidated by the secret police after they give him a visit, eventually beginning to question his own ideals as he succumbs to the fear and intimidation that was a mainstay of the Soviet Union's governing body. Contrasting Fedor personal exploration of Chernoybol with the 2014 Ukrainian uprising, The Russian Woodpecker completes its poignant portrait of the oppressive regime that still exists in the area, as Fedor even quips at one point "the Soviet Union is a creature we haven't beaten to death yet". Featuring a powerful conclusion that sees Fedor stand-up for his beliefs during the Ukrainian uprising, regardless of the threats of violence against those that speak out, Chad Gracia's The Russian Woodpecker and its main subject become one in the same, smart, eccentric, and heartbreaking.  Jason Lei Howden's Deathgasm is the type of throwback film that fans of early Peter Jackson or Sam Raimi are sure to enjoy - an enthusiastically gory horror comedy thats confidence is felt throughout every frame. The story is set around Brodie, a young metalhead who is forced to move in with his relatives after his mother is thrown in jail. A loner, Brodie soon meets Zakk, a fellow metalhead, and the two quickly bond over their mutual admiration for death metal. When Brodie and Zakk stumble across an ancient text, they unwillingly summon malevolent forces, forcing the young friends to go to war with demons for the sake of all of humanity. Deathgasm is the type of horror film which I can't help but enjoy, a gleeful little horror concept which is brooding with energy. The influences of early horror films are very apparent throughout Jason Lei Howden's Deathgasm, from the use of the kinetic, whiplash-like camera movements and quick-twitch editing that would make Sam Raimi blush, to the effective way in which Deathgasm injects comedy into its over-the-top splatterfest. Tongue-and-cheek is certainly a way to describe Deathgasm, never taking itself seriously in the slightest, being a film that's much more interested in providing a unique brand of entertainment, whether through over-the-top violence or absurdest humor. Both the horror and comedy aspects of Deathgasm work, but don't expect a scary film, as Deathgasm is more interested in providing creative over-the-top violence that works well with its unique brand of humor. While one could certainly get picky about some of the characterizations or plot devices throughout Deathgasm that certainly could have been a bit stronger, like the love triangle aspect which feels unquestionably forced, I'd have a hard time being overly critical of a film that more than succeeds at its main intentions, delivering a ridiculously fun horror comedy that blends Heavy Metal and Horror together with highly-entertaining results.  Cary Fukunaga's Beasts of No Nation is a extremely well-acted, well-photographed piece of film-making that unfortunately misses the mark when it comes to being something truly special. Telling the story of Agu, a young boy, who is forced to join a group of rebel soldiers in an unnamed African country, Beasts of No Nation exerts almost all of its energy to capture the loss of innocence associated with these child soldiers, never holding back in its depiction of the primal violence and bloodshed that has essentially become common place in parts of Africa. Beats of No Nation is a film I would describe as all bark but no bite, relying far too heavily on the audience's built in empathy for children forced into battle, unable to ask the tough questions or create its own sense of emotion outside of what is already built in given the subject matter. The film dances around the political and financial aspects of the wars in Africa, as well as the dangers of faith-driven violence, but Beasts of No Nation never attempts to understand them in the slightest, perfectly complacent in simply presenting the brutality of Africans on one and other, in an unnamed country, without even attempting to deconstruct the root of the problem. Beasts of No Nation is powerful filmmaking sure, but it didn't leave much of a psychological imprint on me at all, being more a well-crafted show piece of the darkness of African civil war. Make no mistake, the characterization and narrative of Agu, going from innocent young boy to stone-cold killer is certainly effective at capturing this, but did you really need a film to show you these horrors? Personally, I have questions of why this film was made in the first place, as it feels a little too comfortable simply presenting the brutality of the situation in parts of Africa while never digging deeper, which I'm sure is more than enough for most people, but personally I need more of a reason to bother. The film seems so intent on wowing the viewer with the brutality and unbelievable circumstances that these characters find themselves in that it feels VERY self-conscious, and I'd argue that Fukunaga, who is unquestionable a smart filmmaker, knew exactly what he was doing, as the intro scene, where the boys play with a hollowed-out television, foreshadows the film's own desire to shock and awe the viewer. The loss of innocence aspect of Beasts of No Nation is obviously its strongest attribute, and Fukunaga does do some nice things throughout the film to amplify the tragedy involved in children being forced into conflict. It's used sparingly, but I like how there are a few scenes throughout the film that show the child soldiers playing, like children, as if Fukunaga wants to remind the audience that even though we've just witnessed them commit unspeakably brutal acts they are still children, who simply can't completely expel their youthful exuberance no matter how desensitized to violence they become. Featuring stellar performances from Idris Elba, Abraham Attah, as well as skilled direction for Cary Fukunaga, Beasts of No Nation is a showcase film of performance and direction that unfortunately has little to say outside of what we already know.  John Crowley's Brooklyn tells the story of Eilis Lacey, a young Irish woman, who decides to leave behind her sister and mother in Ireland for the allure of America. Arriving in New York City, Eilis finds it hard to adapt to her new climate, shackled by homesickness and a bit of grief for leaving her sister and mother behind. That all changes when she meets Tony, an Italian immigrant, who sweeps Eilis off her feet with his kindness and dedication, instilling in Eilis a sense that she has finally found a home in America. When tragedy strikes at home, Eilis' past comes back into the picture, threatening to derail everything she has built in America. John Crowley's Brooklyn is a crowd-pleasing, romantic drama that starts strong, but unfortunately withers under the own weight of its dramatic storytelling intentions in the back-half of the film. The first half of Brooklyn offers a poignant portrait of a young woman attempting to step out on her own, capturing the isolation and loneliness that enraptured immigrants stepping into America for the first time. Coming from a small town where everyone knows you to the hustle-and-bustle of New York City is a jarring experience, and Brooklyn captures it well, showing the coldness of New York City from the perspective of its main protagonist. The period setting is well rendered, the characterizations are solid, and the romance which unfolds between Eilis & Tony is tender, sweet, and made me depressed, considering my own shortcomings in the romance department (Yes, this is a complement to the film). There romance feels organic, real, and the chemistry between both Saiusrse Ronan & Emory Cohen is apparent early on. One thing that really surprised me about Brooklyn is just how funny the film is, with a steady stream of laughs throughout its running time that do a good job in the first half of the film of keeping everything even-keeled, considering much of the film early on is centered around Eilis struggle to adapt to her new life. Aforementioned, Brooklyn's back-half, where she goes back to Ireland and flirts with the idea of making her home there, feels contrived, simply there to provide increased drama to what was developing into a nice story of a woman finding her independence and finding her own true sense of home. Its hard to explain without going into detail that I'd rather not spoil, but even though the back half felt forced, compared to the first half feeling very organic, Brooklyn is a film that still works, thanks to its two romantic leads, in particularly newcomer Emory Cohen who really steals the film. While Brooklyn lets its story force its main protagonist in directions that just don't feel genuine, this film is a guaranteed crowd-pleasure which balances poignant drama, romance, and comedy very well.  Thom Andersen, the intricate filmmaker behind such pensive documentaries as Los Angeles Plays Itself & Red Hollywood, returns with his new film 'The Thoughts That Once We Had', a personal love letter to the history of cinema, which is at least somewhat inspired by the books of Gilles Deleuze (The Movement-Image and The Time-Image). While many will write off The Thoughts That Once We Had as the type of film that only cinephiles can enjoy, I'd argue that what Thom Andersen has created with this film is a crash-course in film history which exudes his passion for the power of cinema, an infectious attribute that could serve as a great starting point to those who simply want a better understanding of cinema as an art-form. Running approximately 105 minutes in length, The Thoughts That Once We Had is the filmmakers shortest effort, making it more accessible than the 3+ hour Los Angeles Plays Itself, but that doesn't mean it's any less dense. Featuring very little dialogue, The Thoughts That Once We Had dances with glee through the expansive world of cinema, showing the universal quality of image, contrasting documentary filmmaking, silent filmmaking, musicals, and action films in a way that beautifully expresses how cinema is reflective aspect of life itself. Cinema, and art in general really, are reflective of life, humanity, and society, but Thom Andersen's film takes it one step further, arguing that the true power of cinema lies in its ability to restore our belief in the world. One aspect which really stood out to me about The Thoughts That Once We Had is just how unstructured it can be at times, jumping around the timeline of cinema in a way that gives the film a beautiful, unhinged feeling of exploration. Perhaps the best way to describe the film is that it isn't a story of cinema but rather a love poem, as the film flows freely through the expansive world of the moving image with the passionate filmmakers as our guide. For those wanting a thorough and objective education on film history this isn't the film, but that's what makes The Thoughts That Once We Had so compelling to me, as it's truly a film that exudes the passion of its filmmakers who deliver a powerful ode to the moving image.  A film which can be difficult to watch at times, Hanna Polak's Something Better To Come is a stark documentary chronicling the tough conditions in Svalka, Europe's largest junkyard. Located just 13 miles from the Kremlin, Moscow's extravagant showcase of strength and prestige, Svalka sits, a gigantic trash heap, where many individuals scavenge for survival in a place which more-so-than not is their last stop before death. Being under strict surveillance by Russian police, which allow absolutely no trespassing and no filming, Svalka has become a place of despair, where Vodka is the only currency which seems to matter, and the inhabitants of the dump struggle to survive. 14 years in the making, Hanna Polak's Something Better To Come is a stark and powerful documentary which uses the story of Yula, a beautiful 10-year-old girl who lives in Svalka, to examine the oppressive conditions in modern day Russia. Polak contrasts the abundances of Moscow with the scarcities of Svalka, painting a vivid portrait of a country that has left so many of its citizens behind. Given the subject matter, Something Better To Come is certainly a film that will be hard to watch for some viewers, as much of the film feels very much like a national geographic special of sorts. It's an observant documentary which attempts to simply capture the way of life of these impoverished citizens, whose day-to-day life is covered in despair. As I was watching Something Better To Come I feared it was another shining example of a documentary being praised more for its fascinating subject matter than its artistic merits, but fortunately that concern quickly vanished. Even in this stark, unforgiving world which many of these characters find themselves in, Polak's film captures the triumph of good-will, documenting the youthful exuberance which still exists in the children who life among the garbage, as well as the kindness of many of the adults, who generously share their vodka and last bits of dough or breadcrumbs amongst each other in order to survive. Given that this film was shot illegally, the documentary is very much in a guerrilla film-making style, but what stood out to me more than anything is the complacency in despair which Polak is able to capture. Documenting these individuals who live amongst the trash, Something Better To Come captures how stark conditions and an oppressive, corrupt regime can create a complacency, even in times of absolute stark despair, as many of the older individuals who live in Svalka have lost all hope at any semblance of a better life. Yula is the exception to his rule, a young woman who the filmmakers focus on throughout Something Better To Come, documenting her life from 10 to 24, the heart-and-soul of this story and a truly powerful story of perseverance. Yula is a character who never becomes complacent about the despair she witnesses, intent on leaving Svalka and attempting to make a better life for herself outside of the garage pile. A story of despair, oppression, corruption, and ultimately hope, Hanna Polak's Something Better To Come is a powerful human rights story that pulls back the curtain on a country that has left so many of its lower-class citizens struggling to survive. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed