Macon Blair's I Don't Feel At Home In This World Anymore is a clever albeit dark oddity, a relatively simple story with outlandish designs, a thriller with heavy bouts of comedy that manages to be a rather pointed commentary on humanities' self-centered, me-first, nature, a plea of sorts for a more empathetic world. Centered around Ruthie, a medical nurse, who is going through an existential crisis, I Don't Feel At Home In This World Anymore documents a woman who grows increasingly detached from society, depressed and frustrated by the daily occurrences of self-centered behavior, both big and small, that she witnesses throughout her day. Returning from work one day to find her home burglarized, Ruthie takes it upon herself to track down those responsible after the police themselves prove little help. Driven not by her lost material possessions so much as the principle of stealing, the violation against her personal space and property, Ruthie sets off on a wild ride, enlisting the help of Tony, her oddball, obnoxious neighbor. What starts out as a relatively timid brand of vigilante justice quickly escalates, as both Ruthie and Tony soon find themselves dangerously out of their depth, up against a group of vile, degenerate criminals, who epitomize the self-centered nature which haunts Ruthie to her very core. The inherent selfishness of humanity is an aura that envelopes the entire running time of I Don't Feel At Home In This World Anymore, a film which uses its dark, comedic tone to deliver a wild ride that finds a good-natured woman completely out of her element as she enters the arena of degenerate criminality. Everyone from the police inspector to Ruthie's sister's husband are motivated by their self-centered nature, something which drives Ruthie into a state of depression, and eventually vengeance, but as soon as she finds herself face-to-face with the men responsible for her robbery, she realizes that her fixations may in fact be a bit extreme. I Don't Feel At Home In This World Anymore touches on the inherent selfishness of humanity but also how Ruthie's depression itself only amplifies her own disdain of others, with this journey in vigilante justice serving as a reminder of what true evil is, in the form of these criminals, who have literally no empathy for their common man. Common decency, while a worthy expectation, does not define an individuals overall morality, something which Ruthie's journey exposes in the end, as many of these characters are simply wrapped up in their own problems or personal trauma, most of the time unintentionally slighting others due to their won problems (the police officer would be a good example of this). A common collaborator with Jeremy Saulnier as an actor, Macon Blair's directorial debut shares some similarities with the talented filmmaker, touching on both the toxicity of vengeance, the emptiness or lack of fulfillment it brings, and the general need for more understanding, communication and empathy. Make no mistake, I Don't Feel At Home In This World Anymore stands on its own, but given the low-key, rural nature of the story, as well as the primal/swift nature of the violence and death on display, Macon Blair took cues from Jeremy Saulnier. While I haven't touched on the comedic nature of this film too much, I'd be remissed if I didn't specifically call out the performance of Elijah Wood as Tony. Wood is the comedic relief most of the time, a peculiar, obnoxious character whose off-kilter nature is downright hysterical throughout the film. Macon Blair's I Don't Feel At Home In This World Anymore is a film that manages to balance its serious and comedic elements to perfection, being a darkly funny story full of introspection that never manages to take its foot off the gas, as it transports the viewer into the world of its central protagonist.

0 Comments

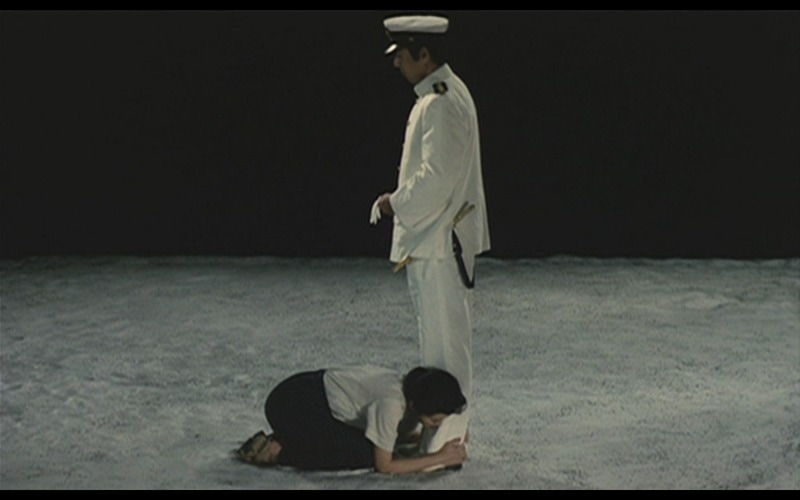

Rosemary Myers' Girl Asleep is an imaginative story of adolescence which uses a heavy dosage of surrealism and impressionistic photography to deliver a truly memorable coming-of-age story about both the treacherous waters of this time and one's life, and the fear associated with becoming an adult. Girl Asleep follows Greta Driscoll, a shy, introsverted young girl who is on the cusp of turning fifteen but remains reluctant to leave her childhood behind. Recently starting at a new school, Greta is a bit of a loner, with her only friend coming in the form of Elliott, a geeky boy who somewhat forcefully injected himself into her world. Comfortable and relatively happy in her quiet existence, Greta finds her world turned upside down when her parents insist on throwing her a surprise 15th birthday party, a decision that sends Rosemary spiraling into a parallel world, a peculiar place in which Greta's adolescent-fueled manifestations of self-doubt, sexuality, anger, and frustration come to fruition in an exaggerated, surrealistic reality. Rosemary Myer's Girl Asleep is a journey into the chaotic mind of a young girl grasping with adulthood, exhibiting not only the fear-inducing absurdities an over-active imagination can create, but also the creative exuberance of a teenage mind trying desperately to make sense of the world. Reminiscent of the films of Wes Anderson early on, Girl Asleep invokes a colorful production design and vibrant visual aesthetic to transport the viewer into the world of Greta, delivering a creative and relatively distinct look and feel that invokes the sheltered, introverted mood of this character, one who lives almost entirely in her own head. While the film's vibrant colorful palette seems to conflict with Greta's introverted demeanor, it provides a startling contrast between her childhood and the vibrant world of adulthood, creating a quirky overall sensibility which aligns with Greta's independence. Shot in 4:3, Girl Asleep routinely takes advantage of its format to provide context, routinely fixating the camera head-on, like a still photography portrait in which she is the center of attention, a visual way of expressing the anxiety triggered by Greta routinely being pulled out of her introverted headspace. This surrealist journey is both confrontational but eventually triggers this character to find solace in her growth, as she begins to find comfort in what can feel sometimes like an incomprehensible new world. Fear of the unknown is simply a part of the human experience, especially during adolescence, and Rosemary Myers' Girl Asleep beautifully encapsulates this through a surrealistic, expressive tone, being honest and creative in capturing the vast changes, both physically and emotional that puberty can have on the psyche through our introverted main protagonist.  Jordan Peele's Get Out is a brilliant piece of genre filmmaking, a film that cohesively blends horror sensibilities with its pointed social commentary about cultural assimilation and race relations, delivering a film which manages to thrill while simultaneously raising poignant questions about the African American experience in the United States. Centered around Chris Washington, a young African-American photographer, Jordan Peele's Get Out chronicles the exploits of this young man as he is roped into visiting his Caucasian girlfriend's family in upstate New York, as the couple has officially reached the 'meet-the-parents' milestone in their relationship. On his arrival, Chris is greeted in an overly accommodating manner by his Rose's family, behavior which Chris attributes to nerves related to their daughter's interracial relationship, but as the weekend unfolds, a series of increasingly bizarre and disturbing occurrences begin to present themselves, with Chris slowly coming to the realization that he himself may be in great danger, due to the color of his skin. From a horror perspective alone, Jordan Peele's Get Out is a twisted, psychological horror film that keeps the viewer intrigued for much of its running time, but where the film excel is its uncomfortable deconstruction of white liberalism in America, where accommodating pleasantries and special treatment mask the underlying racism which exists. Get Out is fixated on exhibiting how the most dangerous threats of racism tend to be the most indirect ones, detailing how Rose's family, a rich, upper-class white family from upstate New York, couldn't be more cordial and inviting to her African American girlfriend, with their racism lurking much more in the shadows. Coming from a VERY 'blue state' and I don't think this is a coincidence, the family members of Rose's family couldn't be more inviting and cordial, but reading between the lines of their kind words reveals an underlying racism, one in which Chris' identity is completely defined by the color of his skin. Many of these characters, while kind in their words, speak in Chris in a manner in which they view all black people as one in the same, with perhaps Get Out's greatest attribute being its ability to capture the collective mindset. All of these individuals view Chris with this collectivist mindset, defining him via their preconceived notions, placing him in the same narrow-minded box which all African American's fit for them, defining him by his skin as opposed to his own individual attributes, like his photography, which is relatively ignored by white suburbia, who can't seem to get enough of his physical attributes. These characters by-and-large are far more interested in signaling their virtue and "progressive" ways of thinking as opposed to getting to know Chris as an individual, and as the film progresses it becomes clear that this is due to their desire for assimilation into their way of life. This is where the convergence of the horror narrative and the social commentary adhere beautifully, as in the back-half of the film it becomes apparent that Rose's family, quite literally, is attempting to assimilate Chris into their way of life through psychological manipulation, and eventually fantasy-horror type brain transfer, with the film racing towards its thrilling conclusion. Chris is routinely complimented for his physique or 'good genetics", but rarely for his photography or general personality traits that make him distinct as an individual, with it becoming clear that Chris is only valuable and accepted by these members in this community if he assimilates and accepts their rules. Get Out uses a fun, thrilling horror narrative to comment on the deconstruction of black culture in America, where mainstream white culture, mostly led by liberals as opposed to conservatives throughout American History, has made it hard for minority groups, specifically African-Americans, to maintain their own, individual culture. Get Out isn't about politics per se, it's about the individualism, as Chris throughout the narrative is routinely identified by the color of his skin, as opposed to his own individual interests and personality. Jordan Peele's Get Out is thrilling, funny, and socially poignant, a rare peace of filmmaking that manages to deliver both populice thrills while also touching on some deeper seeded social issues as it relates to race and culture in the United States of America.  Bette Gordon's Variety is a feminist odyssey detailing the awakening of a character in Christine, a young down-on-her-luck woman who, out of desperation, takes a job selling tickets at a porno theater near Times Square. Stepping into this seedy, erotic social environment, Christine's curiosity is peaked by one of the customers of the theater, a mysterious businessman, whose courtship of Christine only reinforces her curiosities. Becoming increasingly obsessed by the erotic nature of this new social environment which she inhabits, Christine slowly gains a sense of empowerment, growing increasingly comfortable with her own sexuality, as she grapples with female agency in Reagan's conservative America, where female sexuality is taboo, at least when compared to the expressive sexuality men are accustomed too. A story of empowerment, liberation, and sexual currency, Bette Gordon's Variety is a clever piece of filmmaking which uses the narrative lynchpins of a film noir to drive its story of Christine's sexual awakening. Much of the story is centered around her detective-like obsession centered around this mysterious businessman, with Christine following him from place-to-place, intent on getting to the bottom of his profession. The film hints, yet never reveals what type of business he runs, and as the film progresses it becomes quite clear his profession simply isn't important, with the journey itself being symbolic of Christine's own journey of self-discovery. Her intrigue about his profession, the whole mystery/noir narrative could be viewed as simply a symbolic representation of Christine's own sexual awakening, with her curiosity towards his profession representing her own sexual curiosities, as the walls of female agency are revealed to her by this new sexual environment which she inhabits. Christine's relationship with her reporter-friend, Mark, is also revealing, a character who exists outside of the erotic nature of this milieu, a man who repeatedly uncomfortable and uninterested in Christine's budding sexuality, completely oblivious to the fact that his own displeasure simply details female agency, where a woman's outspoken sexuality, unlike their male counterparts, is perceived as taboo by the conservative culture of the 1980s. In one memorable scene, Christine recites a erotic-feminist poem out loud to Mark while he quietly plays pinball, unresponsive to the liberating quality the poem represents for Christine. While Bette Gordon's Variety should be praised for its stunning commentary on feminism and sexual liberation in the 1980s, the film should also be remembered for Luis Guzman's performance in his earliest role as a ticket-taker, a hilariously perfect performance which exhibits who Guzman was an intoxicating comedic performance, right from the very beginning.  The Dardenne Brother's latest film, The Unknown Girl, is another quietly poignant study of humanity and internal conflict, a film that unravels with mystery and intrigue, detailing the exploits of Dr. Jenny Davin, a professional who prides herself on her efficiency. Having recently been chosen to join the prestigious Kennedy Hospital, Dr. Jenny Davin is finishing up her last remaining weeks at her local practice when her service bell rings after-hours. Opting not to open the door, since it doesn't appear to be an emergency, Dr. Jenny Davin is shocked to learn the next morning that there was a death, a possible murder, directly across the street from her practice the night before, with the victim, a teenage girl, being the person responsible for the service bell the night prior. Confronted with her own morality and the guilt associated with not answering the door, Dr. Jenny Davin becomes increasingly obsessed with learning the teenager's identity, an obsession which inevitably threatens not only Dr. Davin's future at the hospital, but also her relationship with patients who might know something about this unknown teenage girl. While some may consider a lesser work from the Dardennes, The Unknown Girl still has a lot to offer, being another engaging, humanistic story delivered in the filmmaker's patented naturalistic style. While not packing the same poignancy as more acclaimed efforts, The Unknown Girl still manages to tap into some universal humanistic truths, detailing the effects guilt and bad decisions can have on the psyche of an individual. Throughout the narrative of The Unknown Girl, Dr. Jenny Davin's world is presented as one in which she is among the fringe or social outcasts of society, with many of her patients being immigrants and sporadic Samaritans, individuals who simply don't adhere to the "norms' or 'standards' one associates with French society. Much of these characters are individuals who struggle, whether it be financially, physically, or spiritually, and much like Dr. Davin, they all seem to be haunted by something from their past, whether it be guilt associated with a decision they made or simply an existential crisis of faith in their actions. While Dr. Davin's story arch sees her get to the bottom of the mystery behind the teenage girl's death and identity, it becomes apparent that The Unknown Girl's story isn't so much about the destination but the journey itself to get there, being a moralistic tale about the weight and psychological impact of guilt, but also the importance and necessity related to fixing what was wrong and making it right. Whether it be Dr. Davin's lab assistant Julien, who is experiencing an existential crisis about his profession, or the victim's sister, who towards the end confesses that her own jealousy leaves her somewhat responsible for her sister's death, the Dardenne's The Unknown Girl is an ode to the need for more empathy, a mature film that recognizes that flaws and mistakes are what makes us human, exhibiting how it's never too late to do the right thing or get on the right path. Dr. Jenny Davin begins to realize her future may be remaining at the local practice instead of going to the hospital, with The Unknown Girl exhibiting a character who internally struggles but eventually reaches a place of comfort in the end, overcoming her guilt and perceived low-morality through introspection and determination. The Dardenne Brother's The Unknown Girl may not pack the same poignancy as some of their other efforts but the film does manage a haunting tale of guilt, intrigue, and empathy, delivering a pensive study of the psychological trauma which guilt can have on the individual while also reminding us as individuals that it's never too late to attempt to make things right.  Ringo Lam's Prison on Fire on the surface may seem atypical of filmmaker's unglamorous action films, being set entirely in a prison, void of the typical gunplay and gangster of his other films that have gained status as 'Heroic Bloodshed'. Yet, all that is changed is the aesthetic of these characters - the gangsters now wear stripes, and the lines between the oppressors and the oppressed are blurred, but it's the film's depiction of male bonding in the face of violence, torment, and pain, that makes Prison on Fire another worthy study of male ethos. The rather plotless story follows the recent incarceration of Lo Ka-Yia, whose been locked away due to involuntary manslaughter after defending his family owned store from a group of street hooligans. Lo Ka-Yia's placement in this prison is much like a minnow being placed into a shark tank, a character whose high-morality and righteous demeanor soon get him into immediate confrontations with various power structures in the prison, including both the guards and the gang leaders who run the operation from the inside. It's through Lo Ka-Yia's friendship he forms with Mad Dog, a seasoned inmate whose unhinged demeanor and carefree mindset help Lo Ka-Yia navigate the tumultuous prison political waters, enabling him to survive his sentence in this foreign, hostile climate. Ringo Lam's Prison on Fire is an intricate examination of prison culture and the power structures which exist within, deconstructing how such a harsh environment as prison often offer no sense of empathy or reprieve, being structures that don't adapt to the individual but rather consume them, presenting a place where the lowest common denominator of morality forces those inside to live by its rules. Lo Ka-Yia is a character who finds himself pushed to the edge by the new, harsh world he finds himself, his own morality tested and abused through a form of psychological torture that finds this character forced to accept a new playing field when it comes to morality and general decency. Mad Dog's unhinged, carefree demeanor offers the only type of reprieve from this hostile environment, something which Lo Ka-Yia must embrace, or at least comprehend, in order to survive. Prison on Fire isn't a film interested in the rehabilitation process, instead Lam's focus is on the bonding effect which such trauma can create, focusing on the unlikely friendship which forms between these two characters. Their time spent together in the course of this story doesn't provide any type of morality tale, rather simply a story of survival while touching on the vast importance of adaptability and bonding in such harsh environment. The finale of Prison on Fire, a brutal ballet of fisticuffs and raw aggression, is a worthy conclusion to Lam's unique prison epic, with the primal brutality on display symbolizing how the power structures of prison breed and manufacture brutish violence where strength and violence are rewarded with power. Ringo Lam's Prison on Fire is not quite like any prison film before it, being simply put, a survival story focusing on male ethos under the tumultuous moral conditions of prison.  CGI-infused epic assertions lambast the underlying humanity of Yimou Zhang's The Great Wall, a film which constantly finds itself at odds between its more nuanced story of a man discovering his underlying humanity, and its adrenaline-fueled promises of fantastical blockbuster style action. A film which gained most of its pre-release notoriety due to the criticisms surrounding its casting of Matt Damon in a movie about ancient China, The Great Wall largely dismisses those criticisms, introducing his character as a mercenary from the West, William Garin, who has been hired for a a quest to seek out 'black powder' rumored to be in the far east. Narrowly escaping an attack by nomadic bandits William, along with his close confidant, Pero, soon find themselves in shackles, imprisoned by the guard at the Great Wall. Intent on escaping from The Great Wall, William soon discovers that the enemy of the Chinese warriors is an existential, fantastical threat to all of humanity, forcing William for the first time in his life to fight for something bigger than himself. Yimou Zhang's The Great Wall is a lush, sweeping, colorfully violent aesthetic, a film which feels so intent on delivering an epic experience that it often sabotages its more intimate story about a man discovering his own humanity. Matt Damon's character is a man who has lived the life of mercenary, only fighting for survival but no true purpose other than his own gain. The existential threat presented by this dragon like monsters gives Damon's character a chance to be a part of something bigger than himself, a worthy storyline that is unfortunately fumbled more-so-than not by The Great Wall's intent on delivering excess. The Great Wall is without question a good-looking film, injecting an intriguing mythology that is met with production design that is inventive; almost cyber-punk like in its ability to create fantastical ideas through means which only the Song Dynasty would provide. The main problem here isn't the look of the film, but the plotting itself, as The Great Wall injects too many throwaway moments of excessive action, with sweeping music and cinematography thats extravagance seems to mask its underlying lack of emotional focus. Overall, Yimou Zhang's The Great Wall is dumb fun, featuring a script that can't decide what it wants to be, too silly to be taken seriously as it appears to want to be, which is in contrast to the film's thrilling, all-out inventive action set-pieces, which show no shame in their absurdity.  Embodying the punk-rock, anarchist spirit of the music scene in the 1980s, Susan Seidelman's Smithereens is the story of Wren, a fiery, independent spirit living New York City. Desperately trying to inject herself into the New York punk scene, Wren is a character who is in constant conflict with societal norms, a strong-minded female character whose struggle for recognition in the punk rock/anarchist lifestyle is amplified on a daily basis by her vagabond lifestyle, one that finds her going from place-to-place, fiercely scrambling for basic needs, such as food or a place to lay her head. Smithereens provides a vivid time capsule of New York City counterculture in the 1980s, detailing a character in Wren who bounces from seedy bar, to sweaty night club, intent on injecting herself into this punk rock culture. A character who isn't afforded the same type of recognition or respect as her male peers in this counterculture, Wren often finds herself only accepted due to her physical attributes, with both Paul, a runaway from Montana who lives in his van in a vacant lot, and Eric, a punk rocker looking to return to prominence, affording Wren at times for the purposes of either sex or companionship. Seidelman's Smithereens is a nihilistic film that never seems to seek empathy from the audience, presenting characters who seem to embrace the fringes of society, forming a culture that isn't congruent to the Reagan era of the 1980s. While the film is never outright political, it presents a core of disenfranchised youths, never going out of its way to make them sympathetic, quite the opposite, yet the humanity it presents, paired with a few subtle nods to the Reagan era and the conservative christian culture, provide a powerful testament to this counter-culture among the young, fed up with society's definition of success. Wren's nihilistic ways, her general lack of empathy towards everyone around her, her me-first demeanor seems matched by Eric, but Paul's genuine feelings for Wren provides the only real sense of optimism towards fellow man throughout Smithereens. Wren's toughness and selfishness are revealed as somewhat as a defense mechanism, a way to mask her own insecurities and fragility centered around her lack of success in the punk scene. This way of living, dog-eat-dog nihilism eventually finds Wren in a more fragile place, whose selfish, unhinged desires inevitably seem to have left her in a place a solitude.  A period drama set in 1950's Japan, Kôhei Oguri's The Sting of Death is a minimalist study of the erosive effect insecurity and distrust can have on a relationship, chronicling a couple whose marriage and overall well-being becomes increasingly combustible after Miho, the wife and mother of two young children, discovers that her husband has been having an affair with another woman. As one could probably summarize, given the title, Kohei Oguri's family-drama is not a particularly uplifting experience, rather a stark exploration of psychological torment experienced specifically by Miho, a woman who simply struggles to put the pieces together for the sake of her family, with her new deep-seeded distrust of her husband being the barrier that stands in the way of her finding solace and happiness once again. While timid early on, Miho grows increasingly hysterical, tormented by her fears of being left behind, unwanted. A woman whose seen her idyllic family life shattered by her husband's transgressions, it is nearly impossible for Miho as a woman, mother, and wife, to return to normal psychologically, with her husband's deceit continually haunting her. There is little reprieve throughout The Sting of Death, little hope for these two characters who attempt to salvage their relationship, and the longer the film goes on, the more it becomes clear that both these characters are deeply-flawed, with their relationship being toxic, beyond repair, each character reinforcing each other's own pain and self doubt through their internal struggle. Make no mistake, The Sting of Death is Miho's tumultuous story first-and-foremost, but Kôhei Oguri's film always remains balanced in its deconstruction, being fair to the adulterous husband, Toshio, capturing how he does have remorse, how he does take responsibility for his past transgressions, even suggesting that his own despondency is at least somewhat related to the trauma of World War II. A stark, tumultuous experience, The Sting of Death may not be a 'fun' watch, but the film's craft is very impressive, a film that is subtle in its style, atmosphere, and surrealism, blending the static, intricate compositions of Ozu with the moody, impressionistic atmosphere one is accustomed to seeing in the works of Michelangelo Antonioni. The opening sequence of The Sting of Death is a masterclass in composition, opening on Miho and Toshio engaged in a conversation, Miho lamenting for her husband to come clean about his transgression. Oguri starts the sequence with a shot-reverse-shot, each character having their own frame. As the conversation intensifies, futher details are revealed, as Oguri pulls the frame back, revealing their sleeping children in the background, the filmmaker taking advantage of the depth of frame, using visuals to escalate the stakes, encapsulating how parent's actions, and their relationship, have far-reaching effects over not only their own selves but also their children's well-being. As The Sting of Death progresses, the film becomes increasingly stark and atmospheric, with high-pitched strings being used in key moments to accentuate the tension and subversive psychological state of Miho. Composition and mise-en-scene are intricate yet critical in telling this sorrowful tale of alienation and fractured romance, with Kôhei Oguri often regulating the children of Toshio and Miho to the background, or at least oft-center to the main quarrel, visually expressing how these children are collateral damage of sorts, deeply affected yet completely detached from this betrayal of trust and brooding insecurities that haunt both Toshio and Miho. Masterfully told, Kôhei Oguri's The Sting of Death encapsulates how lack of trust and insecurity often create emotional trauma, detailing in Miho a woman who is slowly consumed by paranoia due to her distrust, unable to discern truth from fiction, due to her husband's past deceptions.  Being a fan of Bruno Dumont since his debut film, The Life of Jesus, I can't help but find myself astonished by the unique and unpredictable career trajectory of the iconoclast French filmmaker, as he has transitioned from, quiet, meditative storytelling to a more tonally manic style, a strange, intoxicating blend of slapstick, absurdity, and surrealism. His latest film, Slack Bay, continues down this more comedic, absurdist route, being a film that completely defies not just genre description, but any true type of written description, a mapcap, surrealist tale that sees the filmmaker leave his patient, meditative style completely in the dust. Set in the early 1900s, Slack Bay takes place on the beautiful beaches of the Channel Coast, where oddball inspectors Machin and Malfoy have arrived to investigate a series of disappearances. A seaside town made up primarily of small community of fisherman and oyster farmers, Slack Bay becomes a popular destination for the bourgeoisie in the summer time, which presents a unique culture clash between these two classes. The focus of Slack Bay is between the Brefort family, a lower-class, strange family of Oyster farmers, who help transport the wealthy back-and-forth across the bay, and the Van Peteghem family, an extremely wealthy family whose mansion towers high above the bay on the hill. When a peculiar romance between the oldest son of the Brefort family, Ma Loute, and the young Billie Van Petehem unfolds, these two families are thrown into a world of confusion and mystification, with their specific way of life itself shaken at the very foundation. Bruno Dumont's Slack Bay is a peculiar, oddly entrancing experience, a somewhat generic class critique and bourgeoisie satire, that feels nothing but commonplace thanks to Dumont's manic style which grants its actors a unique ability to deliver hyper-reality like performances. Juliette Binoche stands out as Aude, a matriarch of the Van Petehem family, whose unhinged performance perfectly serves the cartoonish, madcap tone Dumont is going for. While Slack Bay's overall point may be a little elusive to some viewers, Dumont's film effectively skewers both the upper and lower class families in over-the-top, surrealist ways. While the Brefort family is presented as near savages, cannibals who devour the rich in order to feed themselves, the Van Petehem family is presented as a group of decadent, yet degenerate individuals, who clearly are seeing the effects of inbreeding. These two families, their cultures, way of life, etc. couldn't be presented as more different, both being very much detached from one-and-other, and through Dumont's absurdest farce, he is highly critical of society as a whole, and the vast disconnect which exists between various classes of society on even the most simplistic scale. A high level farce and biting critique of french society and class struggle, Bruno Dumont's Slack Bay is beguiling and enigmatic at times, though its craft, slapstick humor, and absurdity often offset the depraved story that takes some getting used to. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed