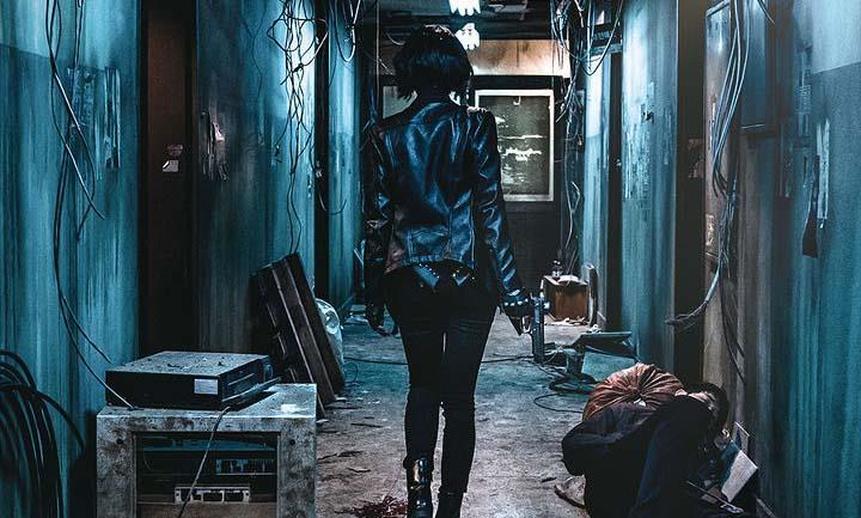

Byung-gil Jung's The Villainess is a visceral experience, an action film full of ingenious designs that places its primary emphasis on delivering an experience that is felt as much as it is seen, with narrative being secondary to the film's lust for delivering heart-stopping mayhem. The first scene of The Villainess perfectly sets the mood for what the viewer is in for, an opening sequence that is a chaotic and ultra-violent, with the filmmakers routinely oscillating their camera back-and-forth between first-person point-of-view and more traditional third person point-of-view, detailing the skilled, brutal work of Sook-hee, a trained assassin, who eviscerates a group of armed men with ease, like a hot knife through butter. This opening sequence, presented as a seamless long-take of mayhem, provides little exposition or explanation for who or what is exactly going on, but through this high-octane, chaotic scene the film lets the viewer know what they are in for with The Villainess, a highly stylized, expertly choreographed action film with a bad-ass femme fatale in the center of it all. While the action throughout The Villainess is clearly a highlight, with the filmmakers delivering a bombastic look-and-feel that combines more traditional photography with a first-person perspective that is engrossing and singular, The Villainess' convoluted narrative leaves a lot to be desired, featuring a messy story about a trained assassin with a mysterious past. Drawing heavily from La Femme Nikita, The Villainess desperately tries to evoke a sense of mystery and intrigue about the past of its main protagonist, a trained assassin working for some form of top secret government organization, routinely oscillating back and forth between past and present as the film crafts Sook-hee's characterization. While the film does reach coherency by the end, it feels too little too late, as the journey itself never pays off, given its unnecessarily convoluted nature. The Villainess' narrative is intentionally vague about the lines between good and evil throughout its running time, keeping the viewer in the dark, much like the main protagonist, unsure about who can be trusted. While this tactic works for awhile, the narrative never provides any truly interesting revelations, being unnecessarily convoluted in its execution, which in turn left me rather uninterested in the story by-the-end, let to focus much of my attention on when the next bit of carnage will take place. Thematically the film works, with The Villainess at its core is a story about female empowerment, detailing a character in Sook-hee whom has been taken advantage and deceived by multiple individuals. She is a weapon whom is effectively used by individuals around her to get what they want, and through her convoluted path of revenge, The Villainess is a story of empowerment, as Sook-hee takes control of her life and extinguishes all the forces around her who wish to control who she is and who she isn't as a person. Featuring some of the most visceral action one is sure to experience this year, Byung-gil Jung's The Villainess is more than satisfying as purely an action experience, but for those looking for more from a narrative perspective, look elsewhere.

0 Comments

Similar to her debut effort, It Felt Life Love, Eliza Hittman's follow-up feature, Beach Rats, finds the talented independent filmmaker return to deliver another compelling examination of burgeoning teenage sexuality, detailing the exploits of Frankie, an aimless teenager living in the outer edges of Brooklyn. Molded by a bleak home life, Frankie is a character who struggles mightily with self-identity, torn between various exterior environmental forces and his own internal desires, detailing a young character who is wholly in a state of confusion about himself, unsure what he wants in life. Beach Rats is an impressionistic exploration of identity and personal desire, a film which manages to detail in Frankie a character who struggles desperately to figure out exactly who he wants to be be, constantly in state of unrest, confusion, and longing, unable to cut through the clutter of both personal tragedy and social pressures and define who he is as an individual. Externally, the world around Frankie is one that values unbridled masculinity and toughness, yet internally this is a character very much at a place of vulnerability, struggling to cope with his father's cancer and a household in disarray. Frankie's sexual attraction to other men conflicts with societies' designation of what he should be as a young man, causing much strife the psyche of this character who struggles desperately to find purpose and define himself as an individual. Artistically-rendered, Hittman's overall aesthetic is very much rooted in evoking a sense of intimacy in this introspective character study, featuring a lens that features a heavy dose of tight-knit compositions which are used to evoke our main protagonist's sense of isolation and solitude, detailing the internal confusion of a character who is forced to keep his sexual yearnings very close to chest. Frankie's inability to be honest with himself first-and-foremost eventually leads to violence and pain for others around him, as Beach Rats' narrative exposes the toxic nature of internal deception, revealing how self-identity and self-honesty are paramount to one's overall mental well-being. Frankie is a character who never manages to be honest with himself or comfortable in his own skin, and his inability to reach a place of solace when it comes to personal identity leaves him tortured, unable to break free from the external elements of his life which currently define him. Unsentimental and frank in its assertions about the importance of self-identity as it relates to overall mental health and self-worth, Eliza Hittman's Beach Rats narrative features a more general, familiar approach than her previous effort, yet this doesn't stop the film from being another powerful evocation about burgeoning teenage sexuality and the confusion it can cause in the psyche of those who are simply trying to define themselves as individuals.  A not-so-subtle evisceration of our over-exposed, self-absorbed culture that has only expanded under the guise of 'the shared experience' predicated and promised by social media, Ingrid Goes West is a dark comedy following the exploits of Ingrid Thorburn, a deeply-damaged individual whose become completely unhinged, conflating social media gestures such as "likes" or "favorites" with meaningful relationships. When Ingrid becomes fixated on Taylor Sloane, an instagram-famous "influencer", she hastily moves to LA, intent on insinuating herself into Taylor's life, desperate to cling to the chic, carefree lifestyle which Taylor exudes in his instagram profile -an outward facing presentation of happiness, creativity, and freedom. Matt Spicer's Ingrid Goes West is sharp, biting satire that features a roller-coaster ride of a narrative in which the viewer simply feels along for the ride, bedside companion with this borderline disturbed main protagonist who will seemingly do anything to feel influential and important. Ingrid is a deeply-troubled individual, a woman whose loneliness and isolation have caused her to grasp desperately for any form of happiness or companionship since the untimely death of her mother, and as her desperation increases she goes to extreme lengths to befriend and ultimately stay friends with Taylor, obsessed with conforming to Taylor's outward social media presentation of what it means to be happy and alive. Going into Ingrid Goes West don't expect an contemplative evocation on mental illness but what the film lacks in introspection about loneliness, isolation, and depression, it makes it for its critique of our image-obsessed culture, beautifully revealing the alienating aspects of social media, showcasing how it often breeds conformity and is at odds with individuals and the important notion of being oneself. While not afraid to deviate into darkness, Ingrid Goes West overall maintains a relatively light tone, considering the subject matter, intent on playfully deconstructing our self-absorbed culture that has only been reinforced by social media, one where we desperately grasp for outside confirmation as it pertains the positive components of our self-image through 'likes". The film doesn't show much interest in deconstructing whether social media is the problem itself , or merely a symptom of a much larger disease, instead Ingrid Goes West focuses on how it's a tool that reinforces an individual's penchant for only seeing the worst in oneself, while at the same time only seeing the best in others through social media applications, where individuals present themselves in a way in which they want to be seen, a mirage, that simplifies the complexity of all of us, only showing the socially acceptable-side, one that is happy and carefree, while neglecting the other side of the spectrum, the one which all of us as individuals are much more terrified to share due to feeling vulnerability about our perceived shortcomings. In a sense, Ingrid Goes West is not simply a criticism of social media, but a statement about individualism and self-sufficiency, detailing how self-care and self-ownership of one's happiness and worth is essential. Ingrid is a character who goes to extreme lengths to feel important and liked, yet she ultimately fails over-and-over due to her fears of simply being herself, fixated on other people's ideals of what it means to happy and successful.  An intimate exploration of what it is to love, Antonio Santini & Dan Sickles' Dina is an engrossing documentary that profiles the uneasy yet evolving relationship between Dina and her fiance Scott, following them in the months leading up to their wedding day. Both of these characters are somewhere along the autism spectrum, where precisely is intentionally unclear to the viewer, and through its pensive, static lens, Dina deconstructs the relationship between these two characters in a way that is both deeply personal and profoundly honest, while managing to tap into universal truths about love and companionship. Shot in a style that reminded me some of Ulrich Seidl, the filmmakers rely heavily on long static photography, the type of compositions and overall aesthetic that is intimate and observant, documenting these two individuals from a distance in a way that never feels the least bit intrusive. Managing to be both uproariously funny one minute, and introspective another, Dina is a film which manages to never reach for comedic aspirations at the expense of its characters, quickly dashing the potential exploitative qualities that ruin many films of this ilk. While Dina is without question the main character, it's through the portrait of these two characters in which Dina as a film manages to tap into the fundamental nature of companionship, detailing the highs and lows of any relationship, the insecurities and frustrations that arise, and the intrinsic need for sacrifice and honesty, exhibiting how with love, two individuals personal problems are now shared. For Dina and Scott, their main struggles relate to physical intimacy, with Dina being far more experienced and one with her carnal desires, while Scott is far more insecure, becoming uncomfortable in the face of merely hand-holding. Through these two character's struggles to express themselves to each other and work through their sordid issues, Dina as a film creates a compelling account of two individuals determined to carve out a future together, detailing how a large aspect of love is rooting in determination, faith, and commitment , as both Dina and Scott each at times struggle with their internal doubts/insecurities. Regulated to the background for much of the film, Dina's personal history is one that is plagued with trauma and heartbreak, yet the film doesn't let Dina's past disrupt the linear progression of the story, only detailing this past through abrupt stylistic moments, a decision which is not only more emotionally resonant in its reveal, but one that also serves a thematic assertion. Dina was violently stabbed in her past, and while the documentary hints at this early on, it only reveals her backstory fully towards the conclusion of the film, detached from the narrative thrust of Dina and Scott's progression to marriage. There is a darkness lurking in the past, one that infects the present in that it fuels Dina's insecurities, yet the presentation of this past trauma is a statement by the filmmakers, one that thematically asserts that love and companionship are far from easy, showcasing how we as individuals are all shaped both positively and negatively from our past experiences, and true love comes from sacrifice, understanding, determination, and mutual empathy. An eccentric love story that is funny, endearing, and introspective about love and companionship, Antonio Santini & Dan Sickles Dina is a testament to the power of intimacy and the resolve.  A vibrant, intoxicating descent into a chaotic and depraved adventure, Ben & Josh Safdie's Good Time is in essence a twisted amusement park ride, a film which documents one night in the life of Constantine "Connie" Nikas, an increasingly desperate and dangerous man, who perilously attempts to get his younger mentally-handicapped brother, Nick, out of jail. Never particularly interested in the conventional side of society , the Safdie brothers have always been filmmakers who've been drawn to the downtrodden or fringe members of society, detailing characters' who've effectively been forgotten or overlooked in the day-to-day of modern civilization. one's who've been hardened or worse, effectively destroyed, by the cold, harsh environment in which they inhabit. With Good Time, the Sardennes brothers document Constantine "Connie' Nikas, a two-bit bank robber who must attempt to clean up his own mess caused by a botched bank robbery that left his young brother incarcerated. He is a deceitful character, a man who will lie through his teeth to those who confide in him, a man who seemingly has a long history of looking out for me, myself, and I first and foremost, which in this case has left his mentally handicapped brother incarcerated at Riker's Island. While one could certainly project some socio-politlcal assertions onto Good Time, the film doesn't feel wholly interested in any such commentary, being a film far more built around delivering a fast-paced, intoxicating journey of escalation, one where the whole narrative feels completely organic, unhinged, and unpredictable. While Good Time feels slightly more polished than the Safdie brother's earlier work, the film still delivers the same down & dirty style, with the filmmakers relying heavily on handheld photography to create a tight, claustrophobic, yet chaotic experience, one that evokes the depraved, increasing desperation of our main protagonist. The Safdie brother's use of sound design in particular stands out, with Good Time featuring an electric soundtrack, one that effectively builds and maintains the tense mood and visceral atmosphere from start to finish. Featuring Robert Patterson in perhaps his best performance yet, Good Time documents a character as he ping pongs from location-to-location, with things seemingly only getting more and more complex as he goes, in a race against time when it comes to saving his brother from a place he himself is responsible for placing himself in. Far from a sympathetic character, Constantine is a lightning rod for the viewer, a character whose actions and circumstances are unpredictable, often vile, yet intoxicating to the viewer, taking the audience on a depraved ride from start to finish. There is no master plan, no grand scheme, as Constantine is a reactionary character, a increasingly desperate man whose path to his brother feels insurmountable and increasingly complicated, leading to a finale that feels almost inevitable. Visceral, intoxicating, and alive, the Safdie Brother's Good Time is a tense and engaging thriller, documenting the exploits of an anti-hero who desperately tries to save his brother from a fate he himself placed him in.  Set in Manhattan in 1995, Gillian Robespierre's Landline is a story of family dysfunction, detailing the Jacobs' family whom appears to be coming apart at the seams, as various members struggle to strike the right balance between personal fulfillment and familial obligations. While every member is going through a personal crisis of sorts, Landline focuses on the two siblings of the household, Ali and Dana, whom soon discover that their dad is having an affair. Landline is an honest and mature comedy about marriage, love, family, and identity, a film that wisely doesn't attempt to make broad stroke moral assertions. never vilifying any of its character's for their poor decisions, understanding that human emotions are messy and honesty about this is paramount to reaching a better place of forgiveness, acceptance, and peace. While Dana uncovers her own wild side of sexual freedom and lustful aggression, teenage Ali is stuck in the middle of adolescent malaise, a character who wants more personal freedom from her perceived overbearing mother and father, lashing out through skipping school and sporadic drug use in an attempt to feel like an independent adult. While many of characterizations of the film are relatively multi-dimensioned, Landline's biggest fault is how much time it dedicates to Ali, whose personal struggles are the most conventional and uninteresting in the film. She is really the only characterization that has the stench of "we've seen this character before", a rebellious adolescent whom is surrounded by much more interesting characters. The lens for the audience is through the two siblings, yet I couldn't help but wish the film would have spent more time detailing the frigid and increasingly broken relationship between Alan and Pat, a couple who've grown further and further apart, with Alan resorting to having an affair in some poor attempt to feel alive and desired again. Perhaps the most salient assertion Landline is able to produce is the absolute necessity of personal identity, detailing through this dysfunctional family how healthy relationships and love are best formed when each individual is comfortable with themselves. Landline as a film wholly acknowledges how difficult it truly is as individuals to discover and comprehend exactly what we want, yet acknowledges the importance of this, particularly when it comes to family and the general search for companionship or love. Charming, funny, and sincere, Landline's ensemble effectively taps into existential questions about personal doubt, worth, and ambition, deconstructing what a family truly is - a group of individuals with their own feelings, dreams, and ambitions, whom love each other despite their differences in what they want personally out of life.  Heavy in grindhouse motifs, both in style, sleaze, and brutishness, Michael Ritchie's Prime Cut sees the mob picture journey to the heartland, following the exploits of Chicago tough guy-for-hire, Nick Devlin, who is brought on by the mafia to collect on an overdue debt from a malicious meatpacker, Mary Ann. Prime Cut flips the traditional fish-out-of-water story on its head, detailing the cultural confliction which exists between urban and rural ways of life, finding Nick Devlin's tough guy persona stuck in a world he has little understanding of, soon discovering that Mary Ann's meat packing plant isn't just for beef, but also human meat, with Marry Ann selling doped-up young girls into sex slavery. Prime Cut is lean-and-mean, giving Lee Marvin a role he was certainly built for, delivering a performance that is calm, cool, collected, yet dangerous, a man who oozes confidence and a quiet, menacing masculinity. The man standing in his way, Mary Ann, is a much more free-wheeling, carefree character played brilliantly by Gene Hackman, who displays this character as a deadly cowboy- a crude, wild persona whose outward personality is playful. A filmmaker far from known for this type of subject matter, Michael Ritchie's direction is impressively assured and ingenious, drawing heavily from the chaotic camera work heavily used in grindhouse cinema - jagged editing, subversive compositions, and a frantic pacing, using it all to aid in evoking the psyche of our main protagonist, displaying a rural setting to the audience that feels chaotic, foreign, and subversive. While the characterizations of the two leads perfectly align with the film's overall juxtaposition of the cultures of rural and urban america, Prime Cut also seems to subtly make a statement about the Vietnam War. While it is never shown on screen, Prime Cut takes place at a time where the Vietnam war is ending and soldiers are returning home. In this heartland, which has always had a reputation for its wholesomeness and morality, a demon lurks in the wheat fields in the form of Mary Ann. He is an important person in the town, but he exploits them in nearly every way, with his greatest crime being the sale of doped up young women into sex slavery, while he simultaneously runs his profitable meat business, Prime Cut as film subtly suggests that there is enough injustice on the home front, in the heartland, imploring that we should take care of the everyday transgressions before acting on perceived problems in foreign lands.  Kogonada's Columbus is a beautiful film. one about balance and symmetry, both figuratively and literally, a meticulously crafted piece of art thats technical prowess is only matched by its meditative evocation about the existential search for identity. Set in Columbus, Indiana, the story is centered around the unlikely friendship that develops between two strangers in Jin, a Korean-born man who arrived in Indiana to look after his architect father who has fallen in a coma, and Casey, a passionate young woman who was born and raised in Columbus, a character who has opted to care for her mother, a recovering addict, instead of pursuing her dreams in the field of architecture. With Columbus, Kogonada has crafted a stunning work of art, a film in which every composition feels meticulously designed, with heavy use of symmetrical framing that symbolically represents the film's thematic assertions about the need for balance and symmetry in life. The use of empty space throughout the film evokes the underlying emptiness each of these characters are struggling with visually, as both Jin and Casey struggle internally with finding the right balance between their personal aspirations and their social obligations. Early on, each of these character's stories feel like completely separate and singular narratives, with their convergence feeling completely organic, like fate brought each of these character's together. While this convergence of souls could easily have felt cheap or simplistic, Kogonada unfolds naturally, striking a good balance between philosophical and emotional resonance. While Jin has always struggled to escape the shadow of his father, a world-renowned architect, Casey has grown complacent at being by her mother's side, happy with her and her mother's relationship she fears that any change could upset the balance of their life, which has reached a good, healthy place. While both of these character's environments and upbringings couldn't be more different, they share the same struggles related to independence, identity, and self, each of which struggles mightily to find the right balance in life between their personal ambitions and desires, as well as their obligations to those they care about. While Jin's struggles are centered around the fractured relationship he shares with his father, one that has lead to resentment and eventually guilt, Casey is a character whose selflessness has restricted her own personal growth, unable to step out of the shadow of this small environment and experience what the larger world has to offer. Each character is burdened psychologically by their relationships with their parents, and the unexpected friendship that develops between these two helps push them both in the right direction, as they share their doubts, fears, and frustrations, each eventually helping the other reach a better place, finding some form of balance between individual aspirations and family obligations. In the end, Kogonada is a story about the absolutely necessity for balance and/or symmetry in life, telling the story of two characters who both have struggled to strike the right balance, each unable to find their sense of independence, which in turn has restricted them from finding solace, structure, and belief in themselves.  One of the more singular visions of teenage longing, self acceptance, and personal solitude, Ian MacAllister McDonald's Some Freaks is a romantic comedy which chooses to examine the darker side of the struggle to find companionship and personal identity, detailing the toxic and coercive effect which longing can have on the psyche, detailing the cycle of prejudice and possessive nature it can breed in lonely individuals whom haven't learned first and foremost how to love themselves. Centered around Matt, a one-eyed high school senior whom is constantly bullied and picked on at school for being different, Some Freaks details the plight of a character whom feels isolated and emotionally alone, despite being surrounded physically by peers every day at school. When Matt meets Jill, an overweight loner, the two quickly and awkwardly become attached emotionally and physically, with Jill presenting Matt with the opportunity at something he never thought he'd have - love and companionship. When Graduation comes, the two are separated when Jill moves cross-country to go to college, leaving Matt struggling to deal with a long distance relationship, one that see him so far away from this woman he so desperately believes he loves. Strife enters in the relationship when Matt goes to visit Jill, learning that she has recently lost a significant amount of weight, a change that Matt struggles to accept, forcing the young couple to grapple with introspection about who they are vs. who each other wants them to be. A surprisingly mature deconstruction about love and companionship, Some Freaks uses the plight of young Matt and Jill to detail the importance of self love when it comes to companionship, exhibiting in Matt and Jill two characters whom fell for each other more due to their own insecurities and self doubts, grasping to feel wanted or desired so much that they never thought about the long term nature of companionship, one that is rooted in selflessness while empowered by a personal, individual worth. As the film progresses and their relationship unwinds, it becomes clear that Matt and Jill's relationship, while tender and heartfelt, was built more out of convenience and circumstance than general selflessness or love, with Some Freaks detailing how Matt in particular grasped on so tight to Jill out of perceived necessity, having such low self worth that he seemingly believed this was his only shot at love. When Jill loses the weight, her status rises, pushing Matt back into his place of deep-seeded insecurity and combustibility, selfishly consumed by his desire to not lose the girl he liked, viewing her as vapid or a betrayer to him while being completely oblivious to Jill's own choices and desires, one's rooted in her desire to feel better about herself and her body image. Exterior vs. Interior status is explored throughout Some Freaks, not only with Jill and Matt but also with a side character of Patrick, a good-looking, popular character, who himself feels quietly alienated, a slave to societal perceptions of what he should be as a strapping young man, unable to express his more sensitive, introspective side due to always being judged as a more straight-forward, heterosexual male driven by exterior attraction. Through Matt, Jill, and Patrick, Some Freaks' details the prejudices which exist in society on all levels of the social chain, exhibiting how all of us as individuals struggle to find our individualism and selfves among the societal defined notions of what we should and shouldn't be. Self worth, and self discovery are paramount to both personal health and companionship, with Ian MacAllister McDonald's Some Freaks being a unique deconstruction of what it means to love, and the struggles many of us deal with to reach a place of personal acceptance, an identity, where we can truly find companionship.  Draped in mystery and intrigue, Taylor Sheridan's Wind River is an engaging, albeit flawed thriller, a film thats narrative thrust and thematic assertions are eventually let down by a lackluster plot reveal, one that feels abrupt and inorganic, rushed from a narrative perspective, though one could argue it works viewed as a clever allegory for the plight of the Native Americans in North America. Taking place in the desolate, frozen landscapes of Wyoming, Wind River follows a fish-out-of-water FBI agent, Jane Banner, who is called in from out of state to investigate the grizzly murder of a young woman that occurred on a Native American reservation. Unfamiliar with the environment or the customs around this isolate setting, Jane enlists the help of a veteran game tracker in Corey Lambert, an expert of the terrain who has personal ties the murder, being not only friends with the father of the slain young woman, but also a man who himself has had to deal with the utter devastation of losing his daughter far too soon. Taylor Sheridan's Wind River uses its murder mystery narrative to exhibit the coldness, solitude, and often despair plaguing many Native Americans living on the desolate terrain of the reservations, painting a portrait of a culture of men and woman who've been forgotten by America, left on the outskirts of society where they themselves are all they got. While Wind River borders on sensationalist in its depiction of the Native American reserve, showcasing a landscape in which dead-ends breed an infestation of drugs, alcohol, and violence, the film's lead character in Corey Lambert is the driving force between the film's thematic intentions, being a film rooted in self-determination, perseverance, and individual empowerment, acknowledging that lack of control over one's environment is assured by not a finite excuse from degradation and defeatism. Having his own daughter murdered in cold blood several years ago, Corey's search for the truth about the recent murder is both personal and business, with Wind River using this character to showcase the pain and anguish of this small community, the frustrations associated with being left behind, but also the importance of personal resolve, exhibiting in Corey a man whom has already been pushed to the edge of suffering by profound loss, unwilling to give-in to darkness- one who accepts that with emotional pain comes acceptance, and ultimately emotional resolve. The finale of Wind River feels truncated and rushed, with the reveal as to what actually happened to this young woman being underwhelming from a narrative and pacing perspective, though one could argue it's the perfect symbolic representation of the Native Americans as a whole - exhibiting a woman who was violently degraded by multiple white assailants, plundered and left for dead. Taylor Sheridan's Wind River is a film which acknowledges the plight of the Native American population, whom are regulated to the shadows and forgotten by today's society, a film which cries out to this culture with empathy and acknowledgement, while simultaneously touching on the importance of individual empowerment and perseverance, reminding the viewer that an individual isn't defined or condemned by their culture or creed. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed