The opening sequence of Shion Sono's Tag certainly starts the film off with a bang, a sequence of creative carnage that is skillfully photographed and directed, which finds an entire group of young school girls excessively torn to shreds by the wind. The sequence is intense, comical, and excessively absurd, which effectively sets up the viewer for what they are about to experience with Tag, the prolific Japanese filmmakers' latest film. Shion Sono's Tag is a film that doesn't explain much to the viewer throughout most of its running time, leaving the audience just as confused as the main protagonist, Mistuko, who finds herself in a world of chaos, where everyone around her repeatedly finds themselves suffer a gruesome fate. Jumping between what can only be described as alternate realities, Mitsuko finds herself in dangerous and bizarre situations, ones where she is routinely faced with violence and death, with unknown forces seemingly out to destroy her in every alternate reality. Mitsuko is a character who is constantly on the run, and it is only when she stands up to her oppressors that she truly realizes what is going on. I wouldn't recommend reading any further if you don't want me to spoil the film's big reveal, as we begin to realize that Mitsuko is the main protagonist in one of the most successful video games, and her fear is what keeps her stuck in this never ending cycle of carnage. While Tag's big reveal is basically impossible to grasp ahead of time, Sono does does leave hints to what this stories intentions are, as many of these bizarre circumstances Mitsuko finds herself do feel like levels of a video game and the over-sexualized female characters did feel oddly out of place early on, only making sense when we realized they are characters in a video game, an industry that is known for their sexualization of the female body for male entertainment. While one could certainly think Sono's intentions are centered around the misogyny that is rampant in the video game industry, I'd argue that is selling Tag's message short, as the film seems bigger than that, using the video game industry to comment on the oppressive nature the masculine-driven world has on females, using Mitsuko, a character who had her DNA used for the entertainment of men, to do so. Shion Sono's Tag is a not a nuanced film by any means, and while its thematic intentions take their time to reveal themselves, Sono has once again created another singular vision, one that is bizarre, violent, and intellectually interesting all at once.

0 Comments

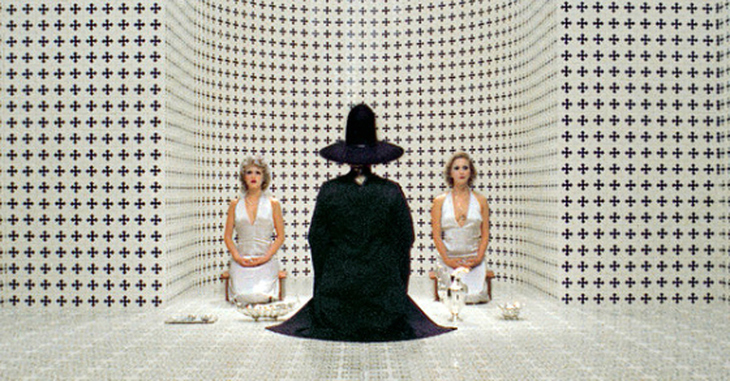

Stephane Brize's The Measure of A Man is a simple yet compelling drama centered around Thierry, a 51 year old man living in France, who is struggling to make ends meat. Being unemployed for the past 20 months, Thierry is desperate to find a new job in order to support his family, a wife and special needs child, facing mounting financial burden in the process. The opening scene of The Measure of A Man perfectly defines the simple yet effective filmmaking one is about to experience, finding Thierry in an intense conversation with a job training company, infuriated that he spent so much time and money on training with no results to show for it. Vincent Lindon in this scene and really the entire film is perfectly judged, a performance that is astonishing in its simplicity and subtlety, evoking a great sense of sympathy from the viewer while doing so in a very naturalistic way. Lindon brings such a quiet sense of sorrow, never overacting at all, though the pressure of providing for his family and the tension from the rate race of looking for a job is felt in his performance. The drama of The Measure of A Man is understated to say the least, but the filmmakers create an overwhelming sense of hopelessness and uncertainty around the character of Thierry, a man who is exhausted from the constant struggle of the job search. Like the Dardennes, The Measure of A Man is the type of film where some viewers will find too little conflict, but what Stephane Brize creates is a film with a quiet anger centered around a culture that puts business and money over the individual. The film documents the struggle of Thierry but it also captures the growing disconnect between personal life and professional life, capturing how the relationships that are made in ones professional life are nothing more than a mirage, defined by a company that can instantly sever any relationship through layoffs or firings. While I'd argue that the film is a tad unfocused from a thematic level, Stephane Brize's The Measure of a Man is a quietly powerful film about a man who is growing increasingly tired of a system that shows little to no regard for people.  Jonathan Levine's The Night Before tells the story of three friends, Ethan, Isaac, and Chris, whom for the past decade, have spent Christmas Eve together to reconnect around a night of debauchery. Now that they are officially entering adulthood, with Isaac expecting his first child, and Chris staying busy with his pro football career finally taking off, the tradition is officially coming to an end. Ethan is still struggling to grasp adulthood, and as the tradition comes to an end, he sets his sights on finally finding the Nutcracka Ball for him and his friends, a party which is considered to be the Holy Grail of Christmas parties. By now most should know what to expect when going into a Seth Rogan/Evan Goldberg comedy and The Night Before doesn't disappoint, being a often funny, crude comedy with heart. While the film oversteps its bounds when it comes to the more dramatic beats of the story, The Night Before excels when focusing on these three man-child type characters, each of which brings their own brand of humor to the table. Typical of these filmmakers the script feels well-written but more like a shell than anything, relying a lot on various improvisation throughout to provide its humor. While a tad strange to say, The Night Before really does embrace the spirit of a Christmas story, juxtaposing the debauchery and antics of its characters with the overwhelming sense of warmth and togetherness that often comes with the Holiday season. If there is one thing that stands out about The Night Before it would have to the host of cameos and supporting performances throughout the film, none better than Michael Shannon as Mr. Green, the local drug-dealer. While only in a few scenes throughout the film's running time, Shannon is an essential character to the story, providing some fantastic comedic moments with his reserved performance. While the dramatic beats of the film just don't work as well as they should, and The Night Before does struggle a bit with pacing in the middle, I'd be lying if I didn't say I had a good time, as the film does a fantastic job at capturing the holiday cheer through Rogen and Goldberg's man-child sense of humor.  Soon-Mi Yoo's Songs From the North is a unique documentary about North Korea in that it never focuses on the tyranny or oppression of North Korea's dictators, instead interested in exploring the people of North Korea and the history of how the country was shaped in the post-Korean War era. Soon-Mi Yoo uses a host of varied media to provide her unique portrait of this enigmatic country, combining interwoven footage from three visits to North Korea, archival footage, popular music and movies, and various stage performances, to observe a country without the typical lens of jinoistic propaganda within the country nor satire from outside it. For lack of a better word, Songs From the North attempts to explore the psychology of a country and its people that has been completely shut off from the outside world, effectively humanizing the millions of people who have grown up in this isolated country. This isn't a film that makes excuses about the countless acts of evil which the leaders of North Korea has committed but it does question how North Korea got to this place, offering a mature portrait of the outside influences of Japan and America being central to the emergence of modern day North Korea. Songs From the North captures the culture of North Koreans and how it is built around overcoming the oppressive outside world, offering a rather startling and fascinating glimpse into the mindset of these people, who have collectively been raised to believe the outside world is a barrier to their success, which has also created a collective love amongst their own people. One of my favorite sequences in the film is when Soon-Mi Yoo simply asks the viewer whether North Korea is the loneliest place on earth, pointing out how it is the only country without allies or even much of history, with its people trapped in this secluded sphere of influence. Through Songs From The North the filmmakers challenge the fundamental meanings of patriotism and freedom, being a film that is effective at helping the viewer come to understand the collective psychology of North Korea.  Patricio Guzman's The Pearl Button feels like a companion piece to his last film, Nostalgia For the Light, being a cosmic, philosophical examination of History, Humanity, Time, and Space that inevitably becomes a film about much more than what it appears in the beginning. The Pearl Button is the type of documentary that is not for everyone, being almost more of a personal essay than anything else, as Guzman waxes poetic about water, its intermediary qualities, and how it connects the universe and humanity in many ways. While the film itself begins very much like a poetic meditation on the blood of life being water, The Pearl Button becomes much more personal and profound as it evolves, transforming into a haunting study of the oppressive qualities of humanity as Guzman examines the violence and death of Chile's past. Focusing on the indigenous people of Chile, those who relied heavily on the sea as their way of life, Guzman provides a meditative study of the importance of water to survival, showing a sense of frustration to the fact that modern day Chile has abandoned one of their greatest resources, the 4,200 km of coastline. Through Guzman's meditative philosophical discussions that at times feel like unfocused rambling, The Pearl Button is able to capture the arrogance of modern day man, exploring how the survival of the fittest principles of life are more linked to aggression than superiority, using the genocide of the Patagonian people in what is now Southern Child as primary example. Part philosophical discussion, part Chile history lesson, Patricio Guzman's The Pearl Button is a film that many will find boring or pretentious, but for those willing to give a film like this a chance, The Pearl Button provides a unique perspective on time, space, humanity, and the universe, essentially being a philosophical examination of the world which we inhabit.  Todd Haynes' Carol is an impeccably crafted piece of filmmaking which follows two women, each from very different backgrounds, who find themselves in a love affair in 1950s New York. Therese, a 20-something clerk, is a character who feels like something is missing in her life, unfulfilled by the host of relationships she has dabbled in. When she meets Carol, a significantly older woman trapped in a loveless marriage, there is an unquestionable attraction, which sends these two characters down a path of forbidden romance. Todd Haynes has delivered another gem with Carol, a film that beautifully understands its characters and their underlying emotions, something Haynes is capable of expressing through this visual medium in a way that is poignant and nuanced. The sense of longing which Haynes is able to create early on is impressive, with the film carrying an atmospheric tension centered around these two characters, each unable to truly be themselves in a world that forbids it. Haynes use of composition is probably my favorite aspect of the entire film, whether it be the way he blurs the image or selectively obstructs the characters, each technique visually expressing the characters inner emotions to the viewer. What I'd like to call isolation framing is a major aspect of what Haynes creates here, where he routinely focuses solely on one character in a conversation/interaction between two, a visual way of capturing the isolation these characters feel, the suppressed emotions that they experience, which makes them unable to truly connect with the other individual in the conversation. The performances in Carol are another stellar aspect, with both Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara embodying their respective characters with nuanced performances. The subtle character traits, which both of these actors bring to their characters is truly exceptional, as simple gestures perfectly en-capture the psyche of their respective characters with great resolve. The story perfectly balances these characters extremely well, and I found it to be an interesting decision that much of their relationship is told from the point-of-view of the younger Therese, a character who is just recently becoming to realize her feelings and sexual orientation. Carol is far from a political film, and really doesn't seem interested in discussing the merits of homosexuality or the oppression of it, rather it simply presents the world these characters lived in at the time, focusing much of its energy on crafting an emotionally resonant story of love and connection, capturing how love transcends gender, which I think is the filmmakers whole point. Another interesting aspect of Carol is the air of misogyny and masculine oppression that engulfs the entire film, as both of these characters repeatedly find themselves having to explain themselves to the dominate, male presence in their lives. This aspect of the film is never overstated, and Haynes never lets it become the primary focus of this beautiful love story, but the oppressive nature of masculinity does feel like a dark cloud hanging over these two characters and their story. A compelling and passionate examination of love and connection, Todd Haynes Carol features nuanced and artistic direction accompanied by two exceptional performances, making it one of the better films to come out this year.  Jonas Carpignano's Mediterranea tells the arduous journey of of Ayiva & Abas, two men making the dangerous trek from Algeria to Italy in hope of a better life. Documenting not only the laborious trek to Italy, but also struggles with violence and hostility when they arrive safely, Jonas Carpignano's film is a poignant and immersive look at the struggle of refugees, being a very timely subject for the current state of world affairs. Jonas Carpignano uses a lot of handheld photography throughout Mediterranea, and while this style of filmmaking is overly used by today's contemporary filmmakers, the handheld is a good tactic for the film, making these two character's emotional and physical journeys much more felt by the viewer with this gritty style of photography. Being a first time feature by Jonas Carpignano, the film does struggle with uneven direction at times, with a few stunningly realized sequences, while others feel a bit contrived. While the final scene of the film is strong and a appropriate climax for the thematic issues the film raises about Refugees, one of my favorite sequences takes place before Ayiva and Abas even arrive in Italy, on a small boat, as they attempt to cross the Mediterranean sea. Venturing into a thunderstorm, Carpignano creates a truly terrifying sequence, with a pitch black frame and the terrified screams of the various refugee passengers, with the only lighting in the scene being provided by the relentless bursts of lightning in the sky. My problems with Carpignano's direction come in a few scenes and shot selections that try to force an emotional reaction from the viewer, as if Carpignano worries that this poignant story of survival isn't strong enough to create his message. It's not overwhelming, and quite frankly I may be nitpicking here, but a few such sequences involving the racist Italian community who show hostility towards Ayiva & Abas feel forced and emotionally manipulative, used solely to trigger an emotional effect from the viewer that was unnecessary. That being said, most of Mediterranea provides a poignant portrait of the daily struggles of men who are simply trying to survive and do what they believe is best for their families. The characterization of Ayiva is really the strength of the film, a man who does nearly everything right when he arrives in Italy, striking up a relationship with a Orange blossum farmer, who quickly recognizes Ayiva's hard work. This relationship is one of the more nuanced and profound aspects of the entire film, being friendly but also restrictive, symbolically capturing this air of racism and prejudice which exists between Italian citizens and refugees. Another interesting aspect of the film are two child characters which Ayiva befriends, a young street hustler & Martha, the daughter of Ayiva's rich boss. While both these characters come from extremely different backgrounds, Mediterranea captures the similarities in their curiosity, innocence and overall lack of hostility towards the refugees, making a point how this hostility which so many adults have towards outsiders is learned over time, not created at birth. Timely and poignant storytelling, Jonas Carpignano's Mediterranea is a beautiful testament to the struggles of those refugees who are simply trying to find a better life for them and their family, as the film simply asks, why can't humanity be more empathetic and less hostile.  Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain is a bizarre, surreal satirical exploration of a man’s quest for his inner truth. On that note, this is not a film for everyone. That needs repeating; this is not a film for everyone. This is the type of film that would shock most casual viewers by its grotesque, yet beautiful visuals and overall unconventional story telling. The Holy Mountain is STILL one of my favorite films because of the challenge it poses to its viewers to think critically, not only about the film but also about their own personal spirituality, society, and religion. The film follows a Christ-like figure that wanders through a bizarre, perverse land where he encounters a mystical enlightened guide, whom sends him on a spiritual pilgrimage. The film is stuffed full of beautiful, however perverse, imagery as the viewer follows this Christ-like figure through his pilgrimage. The most common response to the film is that it attacks organized religion, though this is most likely an effort of average moviegoers to dismiss the film and avoid deeper reflection. Upon closer examination one can see that Jodorowsky was trying to illuminate precisely how primitive our understanding of the world can be. As the theorist Abraham Maslow suggested in A Theory of Human Motivation, self-actualization is the highest stage of human physiological development. This film illustrates the journey to this end. At first glance, the film appears to be a simple hero’s journey, a man seeking truth in a maniac world, but it also must be interpreted as a reflection on both Jodorowsky’s and the audiences’ lives. The Christ-like figure must face the numerous temptations of this world. Along this journey Jodorowsky stresses the importance of making one’s own decisions and the consequences that ensue. In an early scene the protagonist walks through Mexico City to observe all of the city’s grotesque distractions that astonish the eye and confuse the mind. It is a bizarre festival of whores, soldiers, and liars. After taking it all in, the figure then meets priests who befriend him and proceed to mass-produce a mold of him under the promise of enlightenment. They have created a product that is promised to bring clarity, belying their true intention to market it to society, in effect emulating the everyday promises of new technologies. It’s a concept that has been used throughout history. The figure, disgusted by this greed, flees on a journey to find his personal truth. In this way Jodorowsky suggests that man sees the world as chaos. He further suggests that each person must arrive at his or her own conclusions, finding their own personal truth without being alienated by a society whose intentions may be deceptive. The final act of the film is the most linear in that this is when the actual journey towards enlightenment takes place. Our protagonist has faced many challenges on the path to enlightenment: distractions, debauchery, and confronting personal fears. After all the trials and tribulations the figure, and those who have joined him along the way, complete their journey to the top of a mountain. Again this is reminiscent of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, where the ultimate twist is revealed and the alchemist breaks the fourth wall as if to tell the audience, “What did you expect? This is just a movie!” In the end, Jodorowsky does not provide any obvious answers, implying that viewers must find their own meanings and identify their own self-actualization. Jodorowsky makes his final statement about spirituality and beliefs perfectly with this ending, asking each of us to find our own truth because life is a series of experiences that no one can fully understand or can possibly interpret in the same way. The film suggests that society at times can frighten, tempt, and distract, and if one cannot accept these, then they will not experience the pinnacle of true living. Thus, we all must experience life for ourselves, finding truth and meaning in its events as they pertain to our selves. For the film, The Holy Mountain, as in life, one must find their own meaning and develop their own interpretations, this was mine.

Hiroshi Teshigahara's Summer Soldiers is a very different film than the filmmakers typical fare, a low-key, albeit immersive drama that takes a relatively objective look at American GIs who have deserted to Japan during the Vietnam War. Make no mistake, Teshigahara's film could definitely be described an anti-war film, but the filmmaker chooses to examine both sides of the American soldier, focusing mostly on a deserter, but also on the motivations of the American GI who aspire to receive war medals and fight for their country. Focusing largely on a deserter who goes from town to town, Summer Soldiers is a film which could almost be described as a road movie, following this man as he bounces around Japan, exhausted but unwilling to go back to fight in the Vietnam war. While the gung-ho, abrasive soldier is certainly an important aspect for the sake of the film's duality, Summer Soldiers truly shines while documenting the life of this deserter. Teshigahara captures the utter isolation that is felt from a man who is in a country he knows little about, unable to speak the language and trying desperately to survive a life void of fighting in the Vietnam War. His loneliness and isolation are one of the more emotional aspects of the film, as Teshigahara paints a portrait of a man who is utterly alone in a place he doesn't understand. One aspect of Summer Soldiers which I found particularly interesting is how the film captures the importance of individuality over country, as this deserter character does find some solace in the fact that there are Japanese individuals who desire to help him. Teshigahara's film, in a subtle way, turns its nose towards the ideal of patriotism, reminding the viewer that human-beings should not define themselves by country or cree, but only by the desire to support and help their fellow man. Feeling much more like a documentary than Teshigahara's typical art-house fare, Summer Soldiers is a strange, albeit compelling anti-war film documenting both sides of the American GI during the Vietnam War.  Ann Hui's Boat People is a harrowing melodrama that follows the plight of Vietnamese peasants shortly after the fall of Saigon. Centered around Shiomi Skutagawa, a Japanese photojournalist who arrives to document Vietnam's attempts of rebuilding after the war, Boat People delivers a powerful document of the strain post war life has on the less privledged, revealing the horrors which faced the people living in the port of Danang, many of which were forced into labour camps that were hidden by the government with the fancy title 'new economic zones'. This is my first film from the celebrated Chinese filmmaker, Ann Hui, and what jumped out to me right away is the humanistic quality to her filmmaking. Hui delivers a poetic message about people and circumstances, with Boat People exposing how people are typically forced into tough situations with little control of their surroundings. Fatalism is a major aspect of Boat People in that regard, as the plight of many of the characters Shiomi Skutagawa meets along the way feel predetermined, stuck under the crushing regime of postwar Vietnam. The main protagonist being a photographer is no coincidence either, with Hui using this character to make statement about how our perspective of events is routinely framed by photographers, offering only a small piece which may not fully encapsulate the full picture. When Skutagama first arrives he is chaperoned by government officials, who only show happy, healthy children living at peace in quaint villages. It's only when he manages to get permission to set off alone without a chaperon that he discovers the true horror lying beneath the surface. Hui's directorial style, at least in Boat People, is naturalistic with stylistic flourishes, giving the film a documentary-type feel while using well-crafted camera movements to exemplify certain sequences, typically to trigger an emotional response. The characters in Boat people have had their fate sealed by their terrible circumstances, and it should certainly be noted that Boat People is a film that never holds back, offering a few downright brutal sequences at times. Featuring a final sequence that sees Skutagama break the chain of fatalism, sacrificing himself in the process, Boat People is a heartbreaking film about our own lack of control at times, offering a glimmer of hope in the end with Skutagama's selfless act. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed