D.J. Caruso's XXX: Return of Xander Cage marks the reemergence of the mind-numbing action/adventure series starring Vin Diesel , finding extreme athlete turned government agent Xander Cage long thought to be dead, coming out of self-imposed exile to help bring down Xiang, and his team of diabolical baddies, who are intent on recovering the seemingly unstoppable weapon, ominously named Pandora's Box. XXX: Return of Xander Cage is a film that doesn't apologize for its 'cash grab' ambitions and over-the-top cheesy tone, being a film that very much rides on the wave of its outlandish premise, taking every chance it can get to remind the viewer that its extreme athlete protagonist, always, ALWAYS, plays by his own rules. D.J. Caruso's direction itself is so self-aware that it almost feels like the filmmaker is making fun of the story and his own characters, accentuating various protagonist's tattoos throughout the film, almost winking and nodding at the viewer as he proclaims through visuals, "look how tough these character's are! they don't conform to what they man wants! They are rebels". At one point the film even has a sequence between Xander Cage and a potential love interest, where in a moment of intimacy they share each other's various tattoos, sequence that bares a striking resemblance to Lethal Weapon, where Riggs and Cole share battle scars. This film pulls out all the stops in its dedication to romanticizing its counter-culture protagonist, unapologetic in its pursuit of presenting Xander as a character who only does what he wants to do. Everything about this film is drenched in masculinity and renegade culture, with Xander being a character who works with the CIA, not for him, even assembling his own motley crew, one he can trust that isn't directly linked to the government establishment. Riding off the curtails of the Fast and Furious success, XXX: The Return of Xander Cage feels very much like it was created in a think tank, unapologetic in the ways it attempts to mimic the highly successful series, whether it be through the main protagonist's overall brooding, yet carefree attitude, the rejection of all things physics, or the film's overall renegade/ anti-authority attitude which pulsates throughout the entire film at every turn. The team which Xander assembles is one of the more obvious homages/ripoffs to the Fast and Furious franchise, featuring a ragtag group of operatives who themselves struggle with authority and are more likely to be found in a state penitentiary than working for any government agency. While these members serve their purpose, being renegades who Xander can relate to and trust, I couldn't help but laugh at the absurdity of one of them in particularly, a character who is basically a DJ, using his musical skills merely to create diversions throughout the film for his more action-inclined cohorts. While the film does have a few memorable action set pieces due primarily to their outlandish design, the film's action never stands out as a whole, relying far too much on the direction's assured nature, which punctuates moments of chaos as much as possible through composition and speed ramping, with the action choreography itself leaving something to be desired. Drenched in its rebellious, anti-mainstream culture motif, XXX: Return of Xander Cage does present the United States Intelligence community in a very negative light, a film which uses its renegade-fueled-bro protagonist to draw a lazy, but important statement on the US Governments spying program, with Xander Cage even referring to the US government as "just another tyrant" at one point in the film, ooooh how edgy! Much like the first film in the franchise, D.J. Caruso's XXX: Return of Xander Cage is rather enjoyable, big, dumb experience that attempts to piggy-off the success of the Fast and Furious franchise, delivering a film that is unapologetic in its romanticization of extreme sports and renegade culture.

0 Comments

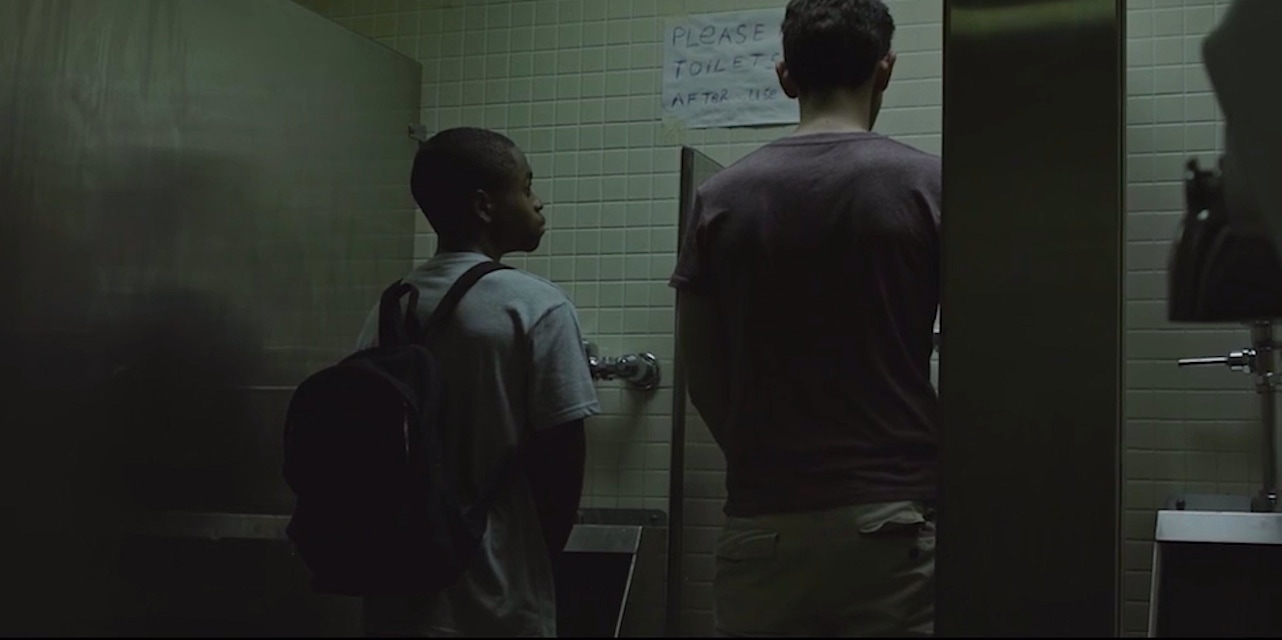

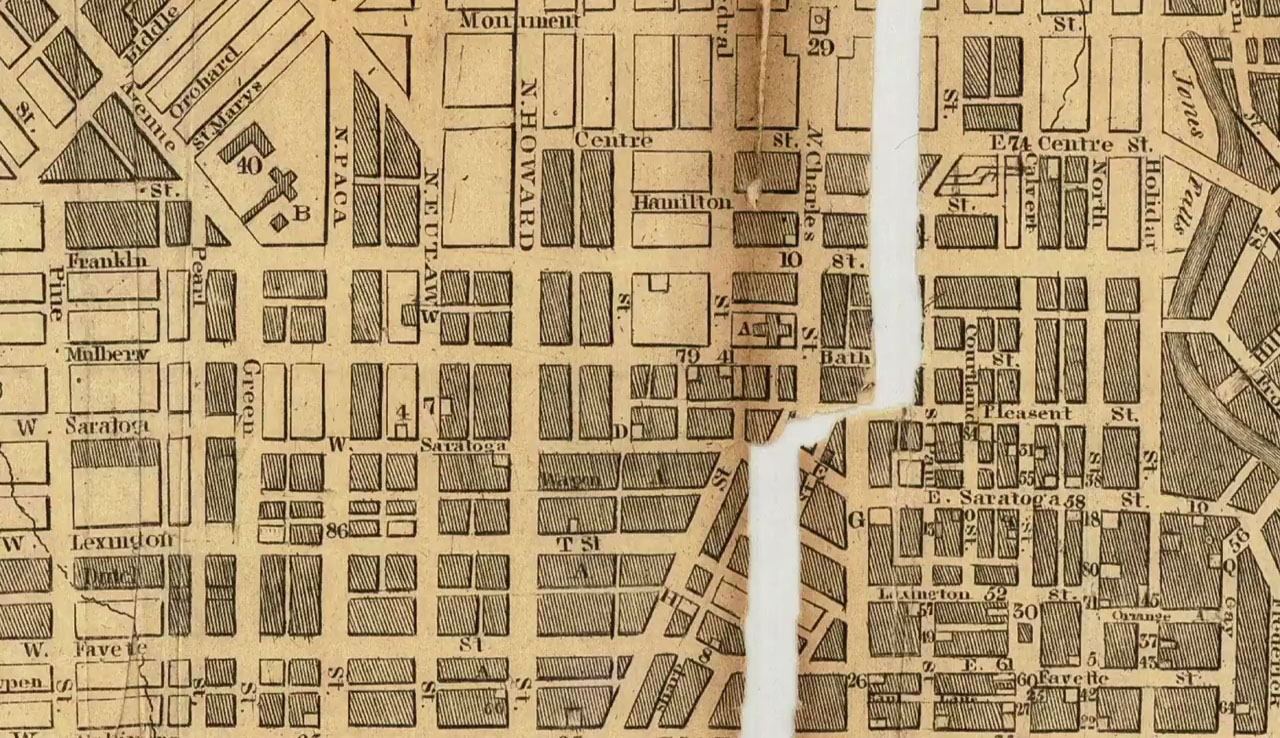

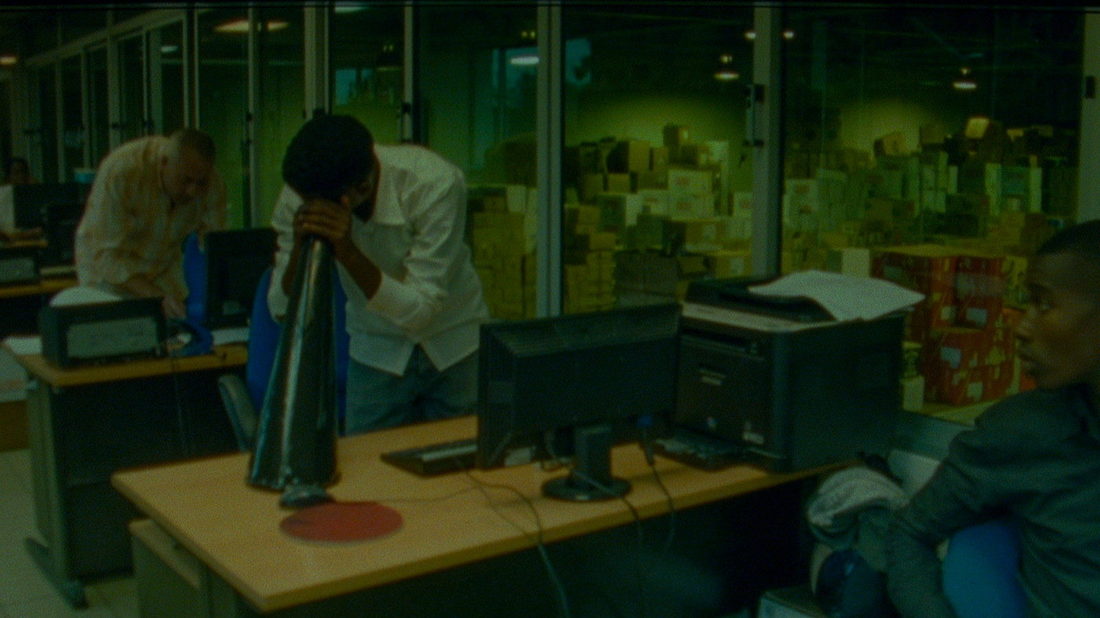

Michael O'Shea's The Transfiguration is a clever indie drama which juxtaposes vampire mythology with the coming of age story to deliver a dark yet compelling story of depression, darkness, and redemption. Introducing the viewer to Milo, a deeply troubled teenager, The Transfiguration identifies a character who lives a life of alienation, spending most of his time alone, fascinated by vampire lore and the overall stench of death. An outcast still suffering from the suicide of his father, and the death of his mother, Milo is a quiet character who has retreated into utter darkness, becoming to believe that he himself is a vampire. With no one but a neglecting brother, who himself seems to be suffering from type of past trauma, Milo finds himself alone with his own thoughts, slipping further into darkness, showing less and less morality when it comes to the significance of life, embracing death. When Milo meets the equally alienate Sophie, a young woman who has been sent to live with her abusive uncle after the death of her parents, the two form an unlikely bond, one that test's MIlo's increasingly dark behavior which begins to obstruct his understanding of what is reality and what is fantasy in his own life. The Transfiguration uses vampire mythology to deliver a dark and brooding study of personal anguish and depression, deconstructing how the harsh reality of one's environment can driven an individual to lose their own sense of morality, growing completely detached from the significance and beauty of life. Milo as a character is slowly reaching the point where human life is nearly meaningless, and the interjection of Sophie clashes with his dissent, provide limited solace and a sense of purpose to the deeply depressed and brooding darkness of a character whose alienation has turned him to perceived death itself as an ally. For much of the film's running time, The Transfiguration brilliantly never completely tips its hand as to whether Milo is indeed a vampire, blurring the lines at every turn, making it unclear if his past trauma has left him extremely scarred and mentally damaged, convinced of his taste for blood. When one is convinced Milo is indeed some type of vampire, the film subverts one's perceptions, reminding the viewer how much trauma this young boy has been through, witnessing the gruesome death of his own father. Milo's obsession of blood, his desire to taste it, provides this character with some twisted psychological connection to his father, and the fact that Milo routinely throws up after drinking someone's blood, hints that Milo's bloodlust may simply be a strange, twisted therapeutic device driven by his damaged psyche, having absolutely no connection to the mystical vampirism established in literature and movies. While The Transfiguration is a clever deconstruction of depression, trauma, and alienation, the film suffers a tad towards the end, feeling the need to didactically explain Milo's actions towards the end of the film, spelling out how he sacrificed himself for the good of Sophie, the only person who seems capable of triggering Milo's sense of humanity and empathy. This didactic voice-over is so frustrating because of everything that came before it was the complete opposite, as Michael O'Shea had delivered an elusive, brooding film about alienation, depression, and darkness, which didn't need to be explained in its closing minutes. Unapologetically dark, Michael O'Shea' The Transfiguration is a unique deconstruction of the affect mental trauma and alienation can have on the psyche of a young person, using vampire mythology to great effect  Milagros Mumenthaler's The Idea of A Lake is a pensive study of loss and memory, a film which brilliantly deconstructs rhe long lasting impact those who are lost can continually have on those they've left behind, with desth itself being merely a physical construct, and only one important aspect of an individuals' contribution towards others they loved. Shifting between past and presemt, exploring the memories of our main protagonist, Ines, The Idea of A Lake taps into the primal nature of lost, crafting a beautiful tapestry in which both subjective and objective memory play a part in Ines' psyche as it pertains to her father, a man who was taken from her at a young age during Argentina's "Dirty War" which saw many men of political oppositiom to the central authority sent to the gulags or to their death. Being my first film by Argentinian and Swiss filmmaker Milagros Mumenthaler I was wasnt sure ehat to expect from what had been labeled as a family drama, What I got was some truly phenomenal direction, as Mumenthaler manages to balance this family drama with biting realism and surrealist flourishes, a film that artistically exposes the effect long resonating loss has on the individual. In the flashback sequences, Mumenthaler presents the serenity of life as a child, where Ines idyllic summers present her fondest memories of her fsther. In these sequences the filmmaker reveals mostly a suvjextive reality, ever so often obstructing this through the use od Ines' mother, who brings glimmers of objectivism to the past, a character eho subtlely reveals the possibility of dangsr on rhe horizon. While Ines charscter is front and center and her emotional journey unquestionable anchors the film, the filmmaker's still provide strong characterizstioms of both Ines' mother and brother, each who seemingly have been dealing with the loss in different ways. A soul-affirming study of loss and memory that is both haunting and genuinely touching, The Idea of A Lake announces Milagros Mumenthaler as a filmmaker I must continue to keep my eye on.  Tetsuya Mariko's Destruction Babies is a brutal deconstruction of masculinity, violence, and culture, a beguiling film that doesn't provide any concrete assertions, opting instead to simply present brutality in its most raw, stripped down form, forcing the viewer to experience violence through the perspective of a man who is more akin to a rabid animal than any form of human-being with a moral compass. Destruction Babies' plot is slight, introducing us to a character in Taira who picks fights with nearly anyone he comes across, with the film providing absolutely no explanation to why he has such a penchant for violence. The most logical explanation seems to be that Taira thinks it's merely entertaining and enjoyable, brutally attacking individuals purely for the sense of pleasure, with his blood-covered knuckles or battered face from past fights being the only clue or warning to others of his coming aggression. Eventually teaming up with Kitahara, the two go on a rampage through the streets of Japan, with Kitahara being more the opportunist, raising his profile through social media, becoming obsessed with the power this brutality gives him over others, fueled by Taira's strength. Destruction Babies examines the seductive qualities of violence and brutality through Kitahara's opportunism, displaying a timid boy in the beginning who becomes flamboyant and bullish, using social media to announce his dominance to the world. Power is a central theme of Destruction Babies, as the film deconstructs the entangled relationship the human psyche has for it through the character of Kitahara, whose newfound "friendship" with Taira empowers him and gives him a sense of control over the world around him. Running parallel to Taira's brutal storyline is the story of his younger brother, Shota, a character who seems to be a bit of an outsider himself, whose felt a bit lost since his brother simply vanished from his life. Shota is the character who provides some semblance of context to Taira's rampage, a boy himself who seems neglected and detached from his upbringing in a small fishing town with a father who seemingly neglects him, and pays little mind to his son's struggles. Destruction Babies doesn't attempt to define Shota's longing or give any concret explanation for Taira's violence, but it hints at a strangled relationship between father and sons, displaying their father as a neglecting father, providing a hint of insight into how Taira himself may have become such a violent vagabond. In one scene of the film, the father explains to the police that "the troublemakers must leave the town", a seemingly throwaway bit of dialogue which provides context to Destruction Babies observational study of Japanese culture, one which praises toughness and masculinity but could also lead to neglect. Their father has very little screen time throughout the film's running time, regulated to the background, an after thought to the film's narrative drive and characterizations. His absence as a way to visually express the neglect felt by his sons, as well as comment on the larger issues in Japanese society, showcasing how toughness and pressured accountability can also breed detachment and a general lack of empathy. Destruction Babies also seems to be a commentary on the digital age in one way or another, showcasing the detachment both the 24 hour news cycle and social media can create on society, and how it can empower the perpetrators or wrongdoers through their raised status. When the news media and social media pick up the story about Kitahara and Taira's rampage, they become celebrities of sort, not character's who are praised by society by any means, but ones that see their social status elevated, granting the character of Kitahara a form of entitlement, power and control. While Destructive Babies doesn't present modern day Japanese youth in the positive light, the film wisely examines how this is just as much a problem of the older generations, recognizing that societies' problems, even if new, are always shared by those of all generations. Nothing is clearly defined throughout this beguiling and difficult experience, and much is up to interpretation in this brutal film, but what Tetsuya Mariko's Destruction Babies has clearly managed is an observational and confrontational study of violence and masculinity-fueled aggression that forces the viewer to experience an up-close and personal account of brutality in its most raw and unfiltered form.  Theo Anthony's Rat Film is a revelatory documentary, a film which uses Baltimore's most prevalent rodent, the Rat, to detail the troubled past of Baltimore, a city thats government institutions were primarily responsible for not only the white flight to the suburbs, but also the oppression of the black community through coercive financial methods administered by the cities government officials. Examining the history of the rat in Baltimore, the people who live with them, the people who share an affinity for them, and the people who kill them for a living, Rat Film is an experimental-type documentary which juxtaposes the history of the rats in Baltimore with the history of segregation itself, telling a convincing narrative which draws parallels rats and people, while simultaneous capturing how scientific method and government coercion fueled the troubles of my hometown. Theo Anthony's Rat Film is both intimate in its examination of the people of Baltimore, and grandiose in its deconstruction of the social issues the city faces from an historical perspective, showing an affinity for the unique personalities and determined mentality of its people. Detailing major federally funded research about Rats in Baltimore through the years, Rat Film showcases how an ecological approach, raising the standard of living among citizens around Baltimore was never fully enacted, with the government always turning to the more offensive approach, one which only target the rats, instead of focusing on the larger cause, the poverty and poor conditions of many of the communities of the city. Rat Film paints a convincing argument that man and rats share similar traits, detailing John Calhoun's behavioral study of rodents, drawing troubling parallels between the treatment of blacks by the coercive, racist government elements and those of the rats which achieved the higher social status among those in Calhoun's study. A documentary with character, Rat Film introduces us to individuals, all of which have unique ways of dealing with the rat infestation. While one man has a full armory of various pellet gun weaponry for fighting the rat infestation, another set of men resort to turkey lunchmeat, peanut butter, a fishing rod, and a baseball bat, all of which have a shared struggle against the rats who threaten their homes. Of all the colorful characters of the film, the professional exterminator stands out the most, whose philosophical ramblings introduce us to a man whose introspective, empathetic, and hard working, an inspiring figure in the film. Many of these character profiled focus on the offensive strategy of elimination instead of the ecological one, with Rat Film brilliantly capturing the long-reaching effects which racist government coercion has had on the city and its people, detailing how such things have long lasting effects on the culture and lexicon of a community, which still remains relatively segregated to this day, due to wrongdoing in the past.  Featuring nearly any dialogue, Yuri Ancarani's The Challenge transports the viewer into the lavish world of Qatar among the ultra rich Sheikhs, whose passions are fueled by excess and a genuine appreciation for falconry. An observant, non-judgmental documentary, The Challenge explores a unique, never before seen world, one which is dominated completely by men, who spend their fortunes on lavish things, whether that be sports cars, gold-plated accessories, or falcons, anything which serves as both as entertainment and a symbol of status. Directed by Yuri Ancarnai, whom is probably best know as a video artist, whose work has been displayed in museums, galleries and art events around the world, The Challenge features a visual striking aesthetic, offering a host of imagery that I promise you have never seen before. Detailing various Sheikhs as they converge on an area of the desert where this contest of falconry will take place, Yuri Ancarani's film introduces us to a world of excess that is both highly comedic and slightly infuriating, detailing the things men that have it all financial do in an attempt to entertain themselves. From one Sheikh's man who drives a Lamborghini and is always accompanied by his pet Leopard, to another man who arrives by private jet, whose had nearly all the seats removed for the purposes of transplanting the prized selection of falcons for the sporting event, The Challenge details the exploits of these individuals with detail and humor. While lacking judgement is unquestionably a good thing, I couldn't help but find myself wishing that the film attempted to gain more entry into the personalities of these characters, showing little interest in that capacity, totally comfortable simply presenting their lifestyle from an outside perspective. With that in mind, one detail that still stood out to me is the fact that there are absolutely no woman in the entire film, only men, and their sons, a detail that stands as an eerie reminder of the secondary status of woman in this region, who could never have this type of monetary or social status. Perhaps best described as a film about "Men and their toys", Yuri Ancarani's The Challenge is a fascinating expose into the ultra rich of Qatar, exposing the excess enjoyed by these men who look for ways to spend their money for the sake of both status and entertainment.  A self-proclaimed fan of the Berlin school of filmmaking, I was eagerly anticipating Angela Schanelec's latest film, as I've always found her to be one of the most enriching and genuine contemporary filmmakers working today. With her latest effort, The Dream Path, Angela Schanelec has crafted another intoxicating experience which attempts to cut to the core of human emotion through a relatively plotless mood piece, shifting seamlessly from character to character, with many of these individuals only true connection being their sense of loneliness, alienation, and longing. A beguiling experience that is sure to frustrate less adventurous viewers, The Dreamed Path spends a lot of time with two distinct characters in Kenneth and Ariane, each of which are suffering deeply due to the hand that has been dealt to them in life. When we are first introduced to Kenneth he is presented as joyous and carefree, an aspiring singer whose happily in a relationship with Theres, a young woman who is interested in studying language. A frantic call shatters Kenneth's world, as he soon learns that his mother has suffered a terrible accident, a revelation that throws Kenneth into a spiral of depression, as he struggles to deal with the trauma and pain associated with the potential loss of his mother. Kenneth is a character who is completely lost after this tragedy, a man who has lost faith in the future and optimism itself due to this hand which has been dealt. When we leave his character, shifting to the life of Ariane, we see a man in Kevin who is indiscernible from the man we were introduced to in the beginning, a man in pain and anguish who has no peace. Angela Schanelec's The Dream Path shows little interest in defining its timeline, with our only understanding of events coming from the characters themselves, their transformations, nothing more. When the narrative shifts towards Ariana we are not sure if there has been a time shift at first, with the revelation of Kenneth,who has become a homeless man and lost all hope, being the only true indication of a severe leap in time. Ariane has no relationship or connection to Kenneth physically, but shares the similar pain, an actress who herself struggles with a terrible sense of longing, adrift in a loveless marriage, unable to find any semblance of happiness even after she cuts the cord on her failed marriage. For Ariane, she is a character suffering from depression and alienation, a woman who has never been confortable in her own skin, never happy with her own successes in life, stuck in a perpetual state of dreaming she was someone else, free of her pain and anguish. Angela Schanelec's direction is paramount in this exploration of loneliness and alienation, as the filmmaker uses stoic, unconventional compositions throughout, rarely fixating on the character's faces, often focusing on their bodies, voiding the viewer of facial intimacy at times, seemingly an attempt to force the viewer to feel the same cold void as her set of protagonists. Without question an enigmatic experience, Angela Schnaelec's The Dreamed Path taps into the harsh reality of loneliness and internal anguish, a film which details the lack of empathy it creates in all of us, which inevitably leads to some form of tragedy, whether it be through the loss of life or the pain which it causes those around us.  Sporting an aesthetic more akin to horror cinema than introspective drama, Kiro Russo's Dark Skull is a brooding story of grief and self destruction, detailing the struggles of a young man in Elder Mamani, who is forced to take up his father's coveted place in the tin mines in the Bolivian city of Huanuni after the tragic death of his father. Elder is a disgrace to the family, a young man who spends most of his time with the bottle, uninterested in supporting his family and his community which still holds onto the tin mines as their only source of community, camaraderie, and self-worth. Kiro Russo's Dark Skull is as much a story about family and sacrifice, as it is about the stark reality in which miners inhabit, a film which manages to balance both elements quite beautifully as this nightmarish experience unfolds right in front of our eyes. Kiro Russo's direction, use of ambiance, sound, and lighting truly make this film a harrowing experience, where darkness itself is a character, both figuratively and literally. Immersive and moody, Kiro Russo's detailed examination of the harsh conditions of the tin mines feels like a descent into hell, as the filmmaker beautifully uses interlaced editing of the machinery and the clings and clanks as they distort the rock-face to effectively transport the viewer into this troubling profession and the headspace of young Elder, a young man who has no desire to be subjected to these types of conditions. Kiro Russo's use of black space and darkness is truly something to behold, with much of the compositions throughout Dark Skull being filled with significant amounts of black space, a symbolic representation not only of this troubled young character of Elder, but also serving as a reminder of the cruel conditions of this profession. As the film progresses, Elder becomes more and more unpredictable, drawing scorn from other workers in the mine who view him as a distraction at the very least, and potentially even threatening the safety of the operation. No matter how much Elder's godfather attempts to help him into the role, he rejects this life. The ending of Dark Skull perfectly encapsulates the nature of the environment these characters' inhabit, offering up a slight role reversal of both Elder and his godfather, who is now the character who is drunk and needs some form of assistance. A film of such darkness offers only a glimmer of light, not exactly showing that Elder has grown up in this moment, but for the first time in the film, showing that he may have found some form of empathy and comraderie with his community and family. A stark, atmospheric piece of filmmaking that ventures into the heart of darkness, Kiro Russo's Dark Skull is impeccably well made film about grief, camaraderie, and empathy, a story which is both intimate in its drama but grandoise in its deconstruction of this small mining community in Huanuni, Bolivia.  Brazen and enigmatic, Eduardo William's The Human Surge is a film that brings a pensive yet observational eye to the state of the world as we know it, a film that shows no interest in plot, only story and themes, as it attempts to deconstruct the ever changing landscape of our globalized world. Spanning three continents, going from South America to Africa to Asia, The Human Surge examines three sets of young individuals, each sharing a similar form of detachment to how they feel about their place in the world. Adrift and routinely only finding any form of solace with others their age, The Human Surge showcases how this idea of working to satisfy oneself creates a void of emptiness within, as each of these individuals pine for some form of substance outside the monetary system we inhabit. Impressionistic and moody, The Human Surge examines how technology connectivity is a red herring in a lot of ways, blinding the individual to true connectivity and intimacy. All these characters are individuals who are often seen on their phones or the internet, yet they lack any semblance of true happiness, drained by a material system that promises everything except what it means to be human. The use of setting, notably nature-based landscapes, illustrates this globalized convergence of the old with the new world, as filmmaker Eduardo William's seems to be pleading for us as individuals to not lose what makes us human. While The Human Surge is powerful and transfixing, it's short sighted in it's hostility towards work and materialism, as the filmmakers never touch on the positives of such technological progress, focusing solely on the negatives, and detachment it can cause. The film doesn't give a fair shake to the world of possibilities technological progress can provide to those, with the film's only example of this being a sequence which shows teenagers selling their sexuality over the camera of their computer, a quite narrow-minded and pointed way of manipulating the positives of technological connection by showings sexual exploitation. The film ignores the positives such connection can bring, while also fundamentally lacking an understanding of how work itself is one of the noble endeavors, in that it forces the individual to provide for others, not allowing them to simply pine about this and self-absorbed cognitations. Impressionistic, thought provoking, and well designed, Eduardo William's The Human Surge attempts to deconstruct the globilazation of our world, with mixed yet always fascinating results.  Ben Wheatley's Free Fire is a streamlined, no-holds-barred, action comedy which wastes little time in diving headfirst into its brutal action and comedy lynchpins, delivering a gleeful mixture of masculinity-dripping violence and uncouth humor that should be enjoyed by fans of that type of thing. Taking place almost entirely in one location, an abandoned warehouse, Free Fire details a arms sale gone wrong, with two gangs soon finding themselves in a shootout, which both comically and brutally transforms into a game of survival for all individuals involved. Early on, Ben Wheatley's Free Fire shows a great sense of escalation, detailing how these two groups of gangs are on high alert, with the slightest incident sending them to a point of near eruption, as both parties involved show little trust for the other in this world of criminals. When the violence does erupt, for debatablly trivial reasons, it comes furiously, leaving every character on both of the sides of the aisle injured in some form of another, each of which crawling around, screaming at each other - the equivalent of a bunch of children fighting in a sandbox, throwing a fit over who is to blame for this arms deal gone so wrong. Relying heavily on the performances of its actors, most notably Sharlto Copley, Free Fire exhibits the utter stupidity of violence in a very unique way, displaying a group of hooligans who comically fight to survive, with Wheatley placing little emphasis on establishing the good guys and the bad guys in this chaotic display of survival, instead focusing on the utter absurdity of these characters, laughing about how so much death was caused over such a stupid inciting incident. Fast-paced, brutal, and very funny, Free Fire finds Ben Wheatley return to a more playfully toned film, than his previous efforts, with Free Fire taking up the mantra of 'There is no honor among thieves", and using it to deliver a truly entertaining romp where a bunch of low-level criminals whom the viewer doesn't really care about, which isn't a bad thing given the comedic intentions of the film, fight for survival. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed