Joel Potrykus' The Alchemist Cookbook is another singular character study by the indie filmmaker, a film that is based in horror but rejects standard genre classifications, delivering a horrific study of mental psychosis. Potrykus's films to-date have always been fascinating character studies about the fringe individuals of society, the downtrodden, abnormal characters who rarely are captured in the vast scope of cinema. With The Alchemist Cookbook, Joel Potrykus has delivered a story of mental illness with strong horror elements, documenting a loner, hermit-like character named Sean, who lives alone in a small trailer in the middle of the woods where he spends most of his time mixing chemicals of some sort. With the title being an obvious play on the Anarchist Cookbook, Joel Potrykus' film remains intentionally vague about what exactly Sean is up to as a character, offering absolutely no backstory into this character, leaving the viewer questioning what exactly he is doing in this secluded environment. Potrykus wisely lets characterization and the performance begin to unravel the mystery behind Sean, with the audience soon beginning to put the pieces together and realize Sean is a man who suffers from some form of severe mental illness. From the way Sean consumes food in an aggressive manner, stuffing his face in a way that signifies necessity for survival, nothing more, to how he routinely talks to his cat, seemingly his only true companion, The Alchemist Cookbook paints a portrait of a man who isn't all there mentally, never fully revealing why exactly he is in the middle of the woods. How did this character damage his leg so badly? what is he making? Drugs? Explosives? None of this is clearly defined and that's exactly what makes Joel Potrykus' film so fascinating, forcing the viewer to simply spend time with this man, who is clearly suffering from some form of grand delusions. Featuring Joel Potrykus' punk rock style of filmmaking, The Alchemist Cookbook feels completely unpredictable and chaotic, mimicking a character whose psyche itself feels like it is slowly slipping away. Much credit for this also goes to the performance of Ty Hickson, whose performance oscillates between horror, joy, comedy, and depression, a powerful performance that beautifully mimics Potrykus' un-caged style of filmmaking. The sense of freedom in the characterization is something to stands out in Potrykus work, with Ty Hickson delivering a performance that feels unrestricted by traditional narrative devices or a didactic screenplay. As Sean slips further into mental instability, The Alchemist Cookbook escalates in suspense and terror, becoming more and more like a horror film, with Potrykus wisely leaving much to the imagination, using brooding cinematography and sound design that fully embraces the less is more mantra of most good horror films. While the film remains intentionally vague, I'd argue that Alchemist Cookbook is a Greek tragedy, with Sean being a character who was taken advantage of after the death of his mother, essentially being forced to cook drugs for his friend (or brother), Cortez, a character who routinely shows up with "supplies". Cortez is a character that serves as comedic relief, somone who seems close to Sean, but he also importantly serves as a window into reality, away from Sean's delusional mindset. While this interpretation may be way off, that's the beauty of Joel Potrykus' The Alchemist Cookbook, a film that manages to deliver a haunting character study of mental illness while serving as a unique mystery simultaneously.

0 Comments

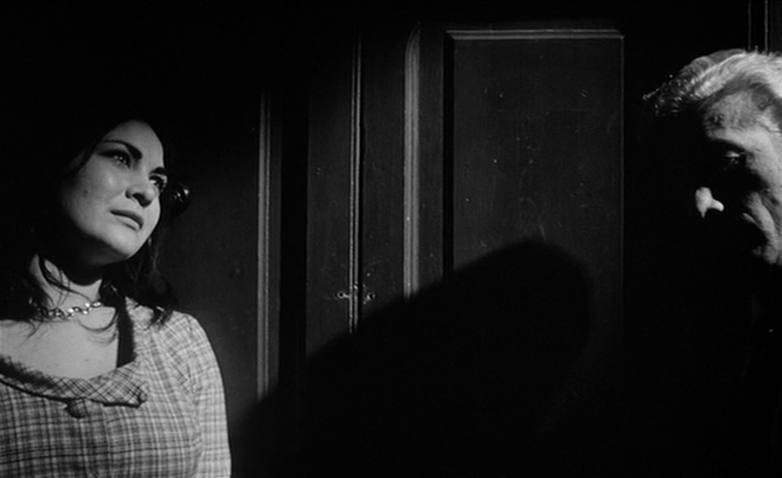

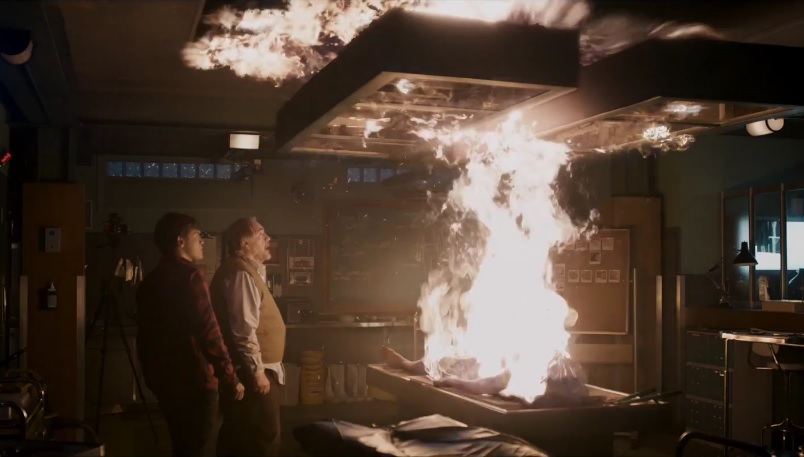

Kimo Stamboel & Timo Tjahjanto's Headshot is a film that wastes no time establishing its intentions to the viewer, opening with a scene of ultra-violence that places psychics and logic a distant second to its masculine-soaked action and bloodshed. Featuring many of the same action and stunt choreographers responsible for Gareth Edward's The Raid series, Headshot is a film that features some impressive stunt work and electric fight sequences, gleefully playing in a world of brutality that is full of creativity and lots and lots of bloodshed. Iko Uwais stars as the main protagonist, a young man who washes ashore with amnesia from a serious head injury, whose diabolical past comes back to haunt him shortly after he is nursed back to health by a young doctor, who unsurprisingly ends up playing the primary love interest in this twisted tale of redemption. Headshot is a film that is so brutal in its violence that it routinely finds the comedy in its absurdity, a film that certainly takes its narrative seriously but simultaneously acknowledges the excessive nature of its violent, blood-soaked intentions. In the middle of intense fight sequences, Headshot routinely uses physical humor to break up the weight of its macho-soaked aggression, with moments of physical comedy, that dare I say, feel like they belong in a Buster Keaton movie- a Buster Keaton movie where broken bones are in very high abundance. I don't want to overstate this unique humor aspect of Headshot, as it could certainly have used a bit more humor, but for a film that is so built around aggression and vengeance, these comedic moments really shine through. While the fight choreography and creativity of violence is without question the most impressive quality of Headshot, the film does feature a host of stylistic decisions such as speed-ramping, frantic camera movement, and expressionist flashback sequences, all of which work to varying effects of success. At times, the frantic camera movements became distracting to the skilled fight choreography, while the speed ramping certainly aided in intensifying the weight of the fight sequences, but Headshot is a film that from a directorial perspective isn't exactly trying to reinvent the wheel, though it's hard to imagine someone not being engaged in this film from start to finish. Featuring a narrative that essentially tells a twisted father/son story on steroids, Headshot is a film that never really achieve many of its more dramatic intentions, with many of the moral repercussions of a man having to come face-to-face with the heinous actions he committed never really paying off. The romantic aspect of the film also feels overly choreographed in the writing, and the film's deconstruction of dependency and morality never comes to fruiition, but its hard to really care all that much when you consider the title of the film is "Headshot", which should make the film's primary intentions quite clear. Featuring a relatively high-concept story that is intriguing though ultimately half-baked, Kimo Stamboel & Timo Tjahjanto's Headshot is an exhilarating action film full of gleeful violence, a film that is sure to enjoyed by anyone who is a fan of action choreography, stunt-work, and bloodshed in their cinema.  An impressive, audacious debut film from iconic Italian filmmaker Bernardo Bertolucci, The Grim Reaper is a clever exercise in narrative, form, perception, and the nature of truth, detailing the mystery surrounding the brutal murder of a Roman prostitute along the banks of the Tiber River. Following the exploits of a police investigator as he one by one interviews a handful of possible suspects and interrogates them, The Grim Reaper details each person's account of the nights' events, offering up a reconstruction of facts which eventually leads the viewer closer to the killer. The structure of The Grim Reaper is dynamic and transfixing, relying completely on these series of interconnected flashbacks to reveal the mystery of the murder. The narrative itself is solely connected by the various eye witness accounts, placing the viewer along for the ride, attempting, much like the investigator himself, to put the pieces together and solve the case. Each of these characters which are brought in for interrogation could be considered people on the fringes of society, outcasts who for one reason or another simply haven't been able to elevate themselves to a better state of living. Whether it is the vagabond soldier who is completely alone, or the street children who "are looking for work" but pickpocket in mean time, nearly every character in The Grim Reaper blurs the lines completely as to whose stories can be trusted or confided in, playing with the viewers' preconceived perceptions, forcing the viewer to routinely question who can be trusted and which characters' stories may be fabricated. While the structure of the film is audacious and should certainly be celebrated, it's once again Bertolucci's stylish visual aesthetic that elevates this film above mere film scholar exercise, featuring stark, black-and-white cinematography which certainly foreshadowed the things to come for this visual maestro. The use of contrast, particularly during the night sequences, mirrors the story itself, with each character venturing from the darkness to the light, and vice versa, visual symbolism which elevates the mystery and intrigue of each of these characters. With no true point-of-view, outside of the police narrator which is never shown on screen, The Grim Reaper's cinematography is never restricted, declaring itself as a unique point of view throughout the narrative as we jump from perspective to perspective, having voyeuristic qualities but also connecting the larger truths of this fateful night. While I'd argue that Bernardo Bertolucci's The Grim Reaper never feels very engaging from a character perspective, the film is sure to be appreciated for its more scholarly merits, playing with structure in a way that creates a fascinating deconstruction about perception and reliability of narrative itself.  A startling tale centered around the illusion of choice, the importance of individuality, and the necessity of personal sacrifice, Elite Zexer's Sand Storm details the struggles of two generations of woman in Layla and her mother, Jalila, who live in a Bedouin village in Southern Israel. Jalila is stuck in an awkward situation, hosting a celebration centered around her husband's marriage to a second, much younger wife. While she attempts to conceal her animosity surrounding this insult, her daughter Layla finds herself falling in love with a fellow student, Anuar, a secret, strictly forbidden romance. The juxtaposition of mother and daughter in Sand Storm is the film's heart and soul, detailing how the mother herself has been beaten down by the harshness of the world in which she inhabits, unable to express the realities of their existence with her much more idealistic daughter, who firmly believes she can marry who she wants if she simply pleads her case. Elite Zexer's Sand Storm is an attack on the traditional culture itself, never placing all of the blame on masculinity for this restrictive, oppressive lifestyle, opting instead to focus on how these traditions have long restricted the individual rights of those who live there. The freedom of choice is a major component of Sand Storm, detailing how not only Jalila & Layla lack any semblance of free will, but how their husband/father, Suliman, himself is merely a pawn to these traditions as well. Many films detailing with the struggle of female rights routinely, and rightfully so at times, demonize masculinity and/or the father figures, but Sand Storm takes on a much more subtle, detailed approach, presenting a man in Suliman who seems to care deeply about his daughter and wife's well-being. While far from the centerpiece of the story, Suliman is a character who isn't simply their to represent the opposition, as Sand Storm presents a fully-developed portrait of a character who himself shows glimmers of personal struggle. Much like his wife and daughter, Suliman is a character who lacks choice in his own life, not free to make his own decisions when it comes to his family's well-being, stuck dealing with ancient traditions which find the tribal society itself declare what is best for the collective. The father is not completely free of criticism, but the opening scene of the film, in which he shares an intimate moment with his daughter, letting her drive home from the village as they discuss her studies is quite revealing. In this intimacy, Suliman treats his daughter like an equal, being a progressive individual in a culture that is so restrictive about a woman's right to go to school or drive. Layla's love for a man that isn't chosen by the elders puts her father in an awkward situation, showcasing how he himself is a slave to tradition, having to do things the way it's decreed to him by this culture. Suliman's routinely is a character who laments that he has "no choice" in these matters, yet through Layla's strong-will and rejection of these restrictive conditions he begins to see the true horror of this culture's oppressive nature, seeing in his daughter a woman who simply wants the freedom to do as she wants. As the story unfolds, Lalya ultimately fails when it comes to achieving her individual freedom, committing the ultimate sacrifice by agreeing to marry an individual she doesn't love for the sake of her family. Elite Zexer's Sand Storm is a tragic film that demonizes a culture which rejects individual freedom and a woman's right to choose, being a humbling portrait of two woman who are forced to live in regime that forcefully dictates their entire life.  Julia Docournau's Raw is best described as a cannibalistic, coming-of-age story, a subversive experience which follows Justine, a young woman, who has just arrived at college for her first year of veterinary school. Justine arrives to a vet school that takes its indoctrination very seriously, with the upperclassman forcing the incoming class to participate in a host of hazing rituals, most notably the consumption of a rabbit heart. A devout vegetarian, Justine is reluctant at first, but through the peer pressure of her older sister, an upperclassman at the school, she eventually succumbs to the pressure. As Justine struggles to fit-in, she begins to experience an unquenchable thirst for meat, a taste which she can't seem to shake, no matter how hard she tries. Julia Ducournau's Raw is a film that shows minimal interest in explaining its depravity through much of its running time, being gleeful dance in the grotesque that only connects the dots towards the very end of its running time. The film is quite peculiar right from the onset, offering a strange mix of comedy and horror that marches to beat the its own drum, as it details the exploits of young Justine, an young, naive girl whose innocence and shy demeanor restrict her socially. Gorehound horror fans may be disappointed in Raw, as the film's strengths relate more to its subversive juxtaposition of social anxiety with that of Justine's thirst for human flesh, detailing a character whose individual awakening just so happens to involve cannibalism. The desire to fit in and be one of the crowd is a concept which Raw uses to its advantage, with Justine's sexual & social awakening going hand-and-hand with her desire to eat flesh, both serving as a quasi-right of passage into adulthood for our young, impressionable protagonist. While Raw isn't particularly gorey, at least compared to a lot of film's out there, Julia Docournau shows an uncanny ability to make the audience squirm, executing the few grotesque horror sequences skillfully, showing a penchant for detail in timing when playing in this macabre environment. Without going into too much detail, the film''s conclusion does an excellent job of bringing clarity to what the audience has just experienced, with many of the decisions made by both Julia, her parents, and her sister, all becoming much clearer when the credits roll. While much of the discussion about Julia Ducournau's Raw is based around its ability to shock and grotesque the audience, what stood out to me about the film is its cleverness, using the tropes of the coming-of-age story to deliver a subversive horror film that is as funny and peculiar as it's grotesque.  Babak Anvari's Under the Shadow is a poignant examination of theological oppression masquerading as a horror film, a story detailing an Iranian woman who struggles to define herself under the Iranian regime of the 1980s. Taking place in post-revolution, war-torn Tehran, Under the Shadow's opening scene finds our main protagonist having her dreams crushed, with her past political activism during the revolution making her deemed unfit to study medicine by those in power. Threatened nightly by the possibility of aerial strikes, this woman and her daugher live in a state of constant fear and anxiety, having very little control over their livelihoods. When her husband is sent to the frontlines, she is left alone with her daughter, with the two of them beginning to be haunted by a mysterious evil which seemingly only comes out at night. A well made horror film full of tension and impending dread, Under the Shadow is a very effective exercise in terror and fear itself, exhibiting how the imagination can run rampant when danger lurks around every corner. The supernatural elements of Under the Shadow could easily be interpreted as something which is completely in the psyche of our main protagonist, being a symbolic representation of an oppressve theology, one that not only threatens our main protagonists' livelihoods but that of her own daugher's ability to live a full life. While the fear associated with the airstrikes certainly plays a factor into the film's study of terror, fear, and anxiety, Under the Shadow lays the seeds earlier to be something much more compelling, showcasing how this woman is extremely liberal considering the environment she inhabits. From her desire to work, to her ability to drive, Under the Shadow showcases a woman who does not adhere to the restrictive nature of the Quran, unwilling to submit to the ultra conservative regime behind closed doors. When the evil presence does arrive it doesn't simply haunt this woman, it also repeatedly tries to turn her own daughter against her, a seduction that seems far too remenscient of an individual conforming to a theological doctrine. This battle for survival against a supernatural foe mirrors a mother's fight for her daughter's independence, unwilling to let this hostile presence seduce her own flesh and blood. Babak Anvari's Under the Shadow is a brooding atmospheric exercise in horror and so much more, using the horror genre to deliver a powerful study of fear, anxiety, and theological oppression, exhibiting one woman's battle for not only herself but her daughter's independence.  Set in the late 1920s, during the height of the Japanese occupation of Korea, Jee-woon Kim's The Age of Shadows is a beautifully photographed, inter-tangled web of deceit, uncertainty, and alliances, detailing the complex cat-and-mouse game which unfolds between resistance fighters attempting to bring explosives in from Shanghai to destroy Japanese strongholds, and the Japanese special police force, hellbent on crushing the threat before they can carry out their mission. Centered around a Lee Jung-Chool, a Korean-born Japanese officer who finds himself stuck in the middle of these opposing forces, The Age of Shadows delivers a powerful study of selflessness and the importance of sovereignty, detailing one man's personal struggle to stand up for what is right in the face of adversity. Working with the Japanese, Lee Jung-Chool is a man who has choosen personal gain and profit over what it right, only beginning to recognize the error of his ways through the men he meets in the resistance, each of which has abandoned their personal fears for the greater cause of independence. Lee Jung-Chool is s character who finds himself forced to choose between his career and his conscience, with The Age of Shadows delivering a powerful portrait of the courage and bravery these resistance fighters exhibited, men who sacrificed themselves for the greater good. The Age of Shadows unfolds in a way where allegiances remain vague and uncertain, exhibiting the commonplace deceit which took place in an era where true intentions and true self were rarely shown on the exterior. Throughout this film's running time, The Age of Shadows rarely tips its hat to the true intentions of its characters, painting a tense portrait of Japanese occupied Korea where no one can be trusted and danger lurks around every corner. Early on in the The Age of Shadows the narrative itself is convoluted, a conscious decision which effectively brings the audience into the environment of its characters, a place where alliances feel like they are constantly shifting and the way characters present themselves never feel absolute. The Age of Shadows is not an easy film to experience, as Jee-woon Kim never shys away from showing the brutality of the era, forcing the audience to witness the brutal violence and torture which took place under the Japanese occupation. The film is a celebration of the sacrifices of these brave individuals but it never glamorizes nor romanticizes their struggle, pensively detailing the great loss of life and brutality bestowed on these individuals who stood up for their independence. Taut, suspenseful, unpredictable, and impeccably well-made in every way, Jee-woon Kim's The Act of Shadows is a harrowing look into the fight for an independent Korea, a film that never romanticizes the struggle and violence while still managing to offer a poignant portrait of the courage and selflessness of the few who fought for the rights of the populace.  While I've always had a strong affinity for a good horror film, the genre rarely manages to actually leave me shaken these days, but with the case of André Øvredal's The Autopsy of Jane Doe, I'd be lying if I didn't say I was left startled by the film's unique vision of terror. The story is centered around Austin and Tony, father and son coroners, whom receive a mysterious homicide victim in Jane Doe, who has yet to be identified by any of the local authorities. Hoping that the cause of death will give them some indication as to who this woman is, Tony and Austin are tasked to perform a seemingly routine autopsy on "Jane Doe" with the intent of discovering the cause of her death. The Autopsy of Jane Doe is the type of film that is best to go into knowing as little as possible, but lets just say that the concept of the narrative is strong and unique, which only works as well as it does due to two fantastic performances by Emilie Hirsch and Brian Cox, as well as some stellar direction. It's rare these days that a movie like this keeps you completely clueless about where it is going for much of its running time, and one of the main reasons The Autopsy of Jane Doe feels so special is its ability to delivery a story that shows as much respect for mystery as it does pure horror, transplanting the viewer into the head-space of both its lead characters who find themselves dealing with some form of supernatural horror. The direction itself sets the tone early, featuring a healthy dose of atmospheric tension through slow, creeping camera movements and a general atmosphere of uncertainty. The director, André Øvredal, has created a film that feels like a horror movie for horror fans, routinely playing with the viewer's perceptions and preconceived expectations of the genre, with beautiful use of repetitive shot selections that throw off even the most ardent horror viewer, making it hard for the audience to predict when exactly the next moment of terror will commence. The Autopsy of Jane Doe is lean, mean, and taut with suspense, grabbing the viewers attention from start to finish due to its effective storytelling and carefully executed narrative. If I had one real complaint about the film I would argue that the finale does feel a bit rushed, with the characters' putting the pieces together and unlocking the mystery in a relatively quick sequence that feels almost out of place due to the film's mysterious tension throughout its running time. The Autopsy of Jane Doe works so well because of its unique story and reliance on atmospheric tension, letting its two lead actors draw the viewer into the story thanks to their compelling performances. While a lot of the more praised horror film's these days seem to have thematic intentions well outside the wheelhouse of traditional horror cinema, The Autosphy of Jane Doe feels refreshing in its thematic simplicity, a throwback film of sorts which delivers a taut, deliciously diabolical experience that is sure to make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up throughout its running time.  A singular vision of a post-apocalyptic environment, Ana Lily Amirpour's The Bad Batch is a twisted fairy tale set in a Texas Wasteland, where those deemed unfit for society have been placed in a world where chaos reigns. The Bad Batch is a film that transplants the viewer into this grotesque world of disorder, where depravity and the battle to survive go hand-and-hand. Juxtaposing the brutality of this world with a healthy dose of pop music, The Bad Batch is a film that seeks to find the humanity and empathy in disorder through its main protagonist, Arlen, a woman who faces extreme violence and pain but never seems to completely lose hope, no matter the obstacles she faces. The Bad Batch is a film that dances around a lot of interesting thematic elements, touching on not only humankind's need for connection, but also the importance of never giving up on those who have been given up on by society. All of the characters in The Bad Batch have been sent to a place of exile for reasons which are never explained, as the film intentionally showcases how their past crimes simply aren't important for the sake of the film's optimistic perspective of the human condition. The Bad Batch is a stark reminder of the importance of empathy, forgiveness, and second chances, detailing how all these characters, no matter how heinous they may act, are creatures of emotion, each which at least in part is a victim of the environment which they inhabit. Ana Lily Amirpour's film is a powder keg of visceral energy, a film that seeks to touch on the very essence of what makes all of us human, with even the more heinous character's being driven, at least in part by their dedication to other. Jason Momoa's character, Miami Man, is a great example of the film's optimism, a brutish man who has completely embraced the violent environment which he inhabits, with his only sense of empathy coming from his desire to take care of his young daughter. The relationship that slowly unfolds between Miami Man and our main protagonist, Arlen, is the heart and soul of the film, which begins to unfold almost like a bizarre love story, as this young woman's dedication to empathy eventually rubs off on this brutish man. Intentional or not, The Bad Batch exhibits the sense of companionship and community that is a fundamental aspect of humanity, showcasing the importance of community but also the inherent shortcomings of such reliance on others through the character of 'The Dream', played beautifully by Keanu Reeves, a man who is dangerously close to becoming a fascist presence, lamenting at one point that he "knows what is best" for the people who confide in him. While The Bad Batch's vision is utterly singular and often compelling, I'd be lying if I didn't say the film at times felt like a missed opportunity, never showing the dedication necessary to deconstruct complicated concepts about governance and societal order. To be fair, Ana Lilly Amirpour simply doesn't seem all that interested in these thematic concepts, as The Bad Batch shows much more interest in simply painting a visceral portrait of the importance of hope and empathy, with its two main characters in Arlen and Miami Man eventually gravitating towards one and other due to their sense of connection to one and other. Skillfully directed, impeccably photographed, and featuring a healthy dose of pop music, The Bad Batch is an electric experience that never focuses too much on intellectual discussions about governance, criminality, and order, opting instead to deliver a singular vision about humanities primal need for connection, perhaps being best described as the cinematic equivalent of pop art.  Bryan Bertino's The Monster is a horror film which tries to hard to be something it's not, attempting at all costs to provide a thematic deconstruction of the coming-of-age story, a decision that seriously hurts the overall effectiveness of its lean, suspenseful, horror structure. Set on a dark and dreary road in the middle of nowhere, The Monster details the battle of survival between a divorced mother and her headstrong daughter, a young girl whose frustrations with her careless mother has reached a boiling point. Early on in the film, The Monster makes it very clear that the typical roles of mother and daughter don't apply to this relationship, exhibiting how the young daughter is the responsible one, tired of her mother's drunken antics and carefree nature. Oscillating between flashbacks of past abuse and the present predicament these characters find themselves in, where they fight for their lives against a terrifying creature of the night, The Monster juxtaposes their home problems with this battle for survival, attempting to bridge the gap of this flawed mother-daughter relationship. Unfortunately the filmmakers have laid on the abuse of the mother far too quick, making it hard for the viewer to relate to this woman, as I found myself wishing for a swift death due to her negligence and overall poor demeanor towards her child. The daughter herself is by far the most compelling character in the film, but unfortunately the whole genre exercise comes off quite predictable due to the film laying on the fractured relationship between daughter and mother too think. In its foreseeable conclusion, The Monster seems to want the viewer to acknowledge the mother's sacrifice for her daughter, giving up her own life in a last ditch effort to show how much she cares. Her sacrifice is supposed to prove her love for her child, but the film doesn't realize it's too little too late to deliver a strong emotional core, with the symbolic nature of the killer creature itself representing the harsh reality of life being far more interesting. Unfortunately, none of the dramatic beats of this story work particularly well, with these characters motivations and desires being presented in a way that is always didactic and overly sentimental, making most of the film's emotion fall very flat. From a technical standpoint, The Monster checks most of the boxes in what I look for in a horror film, being a film that wholly believes in the 'less is more' concept, focusing more on mood and atmosphere than violence to create its suspenseful tale of survival. Featuring practical effects and a voyeuristic lens, The Monster exudes horror and uncertainty for much of its running time, delivering an atmosphere that is dripping with tension, but unfortunately I never found myself caring much for these characters, almost rooting for the creature to eviscerate them due to the screenplay's didactic approach. While The Monster's use of practical effects are very welcome in the world of horror these days, The Monster's stripped down, simple, suspenseful narrative feels wasted due to the film's thematic and dramatic concepts falling completely flat in the end. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed