|

Alexander Nanau's Collective is a meticulously constructed descent into institutional failure. An engrossing investigative documentary that fully recognizes the subject matter itself is the star of its story, Collective employs a structure to its documentary storytelling that allows for adaptability, providing the ability to be seamless in its focal shifts when necessary to document the serpentine labyrinths of corruption that infested the Healthcare system in Romania. The culpability of one or two individuals is not necessarily what Collective aims to elucidate, it instead attempts something far more difficult - understanding the relationship between corruption and power. How such widescale corruption infested and interlaced itself across such a vital institution as healthcare is the chief tenet of this film's investigation, with the sheer terror of what it documents being the fact that such monstrous tragedies develop almost entirely in the darkness, due largely to lack of oversight and accountability due to the authority of the institution itself. The brazen disregard for human life which found them diluting disinfectants 10 times over as a cost-cutting exercise is just staggering from a moral or ethical perspective, yet Collective exhibits how something so unbelievable can happen largely unseen, if not for the essential nature of independent journalism. In a more reductive albeit accurate reading of Collective, the film can be seen as an ode to independent journalism and the importance of a free press when it comes to standing up to power and holding those who wield it to be accountable for their actions and the people they oversee given their institutional authority. It's a very important message in itself, a journalist's only obligation should be to the truth, and yet perhaps the film's largest proclamation remains one of more importance - human rights. Throughout the film's sprawling investigation that is consistently engaging and tactically efficient, Collective is a reminder of the absurdity of placing a monetary value on human life - the preservation of life has no cost and should never be held hostage by the prongs of austerity.

0 Comments

Nothing to see here just Robert Altman mastering another genre of cinema as he ran rampant through the 1970s. Masterfully crafted, visual, and aural elements beautifully coalesce into a brooding, atmospheric descent into psychosis. Lesser directors would be fearful of portraying a character's fragmented psychology with such rigorous commitment, yet Altman lets these delusions linger far longer, effectively shifting the ontological lens into a space in which identity itself for our main protagonist is dangerously fleeting. Challenging the viewer from beginning to end, Images takes advantage of their intrinsic desire for objective truth, crafting a truly memorable psychological horror film that borrows from the best (Hitcock, Bergman) while still spinning something uniquely his own. Susannah York is great in this.

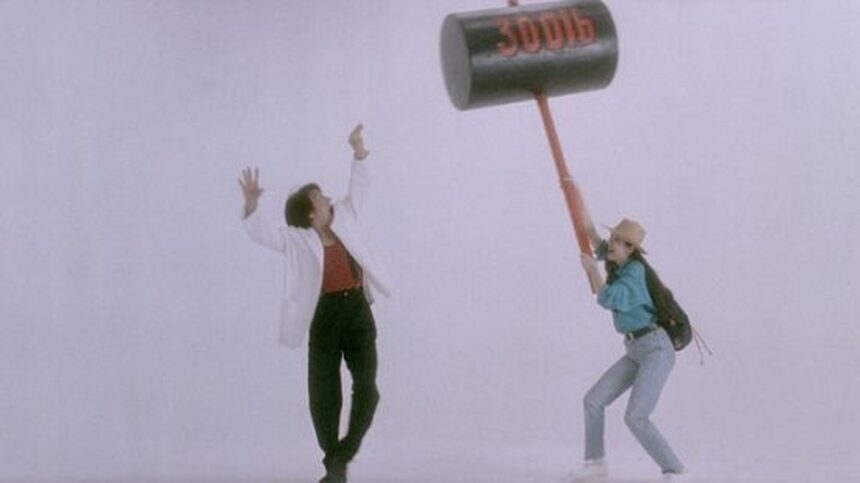

Wong Jing's City Hunter is perhaps the textbook definition of bubble gum cinema - a blissfully dumb, hopelessly endearing film that is self-indulgent in all the right ways, intent on eliciting a response from its audience at every conceivable opportunity. Silly and self-reflexive, the film's cartoonish portrayal of machismo posits masculinity as a force of action over introspection, with City Hunter suggesting machismo shares a direct relationship with abject imbecility. Features perhaps Chan's most bizarre performance, one that's so flamboyant and exaggerated that it feels like he is attempting to channel Jerry Lewis. The results are middling, to say the least, and while City Hunter could be considered to feature Chan's worst performance, the film remains infectious due to Jing's style and aesthetic sensibilities which exude a vivaciousness from beginning to end. Colorful, dynamic, creative, and borderline problematic - the over-sexualization of teenage girls is something that stands out as uh, odd - City Hunter remains a silly, infectious action-comedy that is perhaps best described as Under Siege getting a screwball comedy treatment.

While it can be didactic and prescriptive in its sociopolitical aspirations, Residue remains a strong debut feature largely because of its quiet moments of introspection. These moments are imbued with a lived-in authenticity due to their personal nature, instilling the film with a raw emotional energy that ultimately provides far more credence and poignancy to the film's thematic intentions than its scripted dramatics ever could. Residue at times doesn't seem to trust its audience, expounding its message through some artificial narrative devices which can be grating, yet in these more personal moments of introspection, which are beautifully rendered by immersive aural and visual aesthetics, Residue manages to contextualize the struggle for racial equality in a far more substantive way, through natural, emotional transference. By incorporating identity and memory into its bold formalism, Residue, evokes instead of expounds the panoply of emotions which make up the African American experience in America - pain, guilt, anger, acceptance, etc. run congruent and incongruent, there is no singular way to quantify collective, heterogeneous pain. With that in mind, Residue operates at its best when the personal and collective aspects of identity are interpreted and examined in unison, as the film emotes instead of instructs through its chief characterization. Its message on gentrification is salient yet too forceful at times, unwilling to trust its audience to decipher the vicissitudes of fortune that disproportionately and negatively effect the minority community through its chief characterization alone. Gentrification is merely a symptom of the ills of the larger state apparatus, whose authority under the current polity subverts socially ethical outcomes and displaces communities due largely to the promises of prosperity proposed by capital. A beautiful mosaic at its best, Residue manages to overcome its more detrimental desires to message-make narratively thanks to an immersive formal structure and aesthetic style which signals a belief in the transference of affect.

Featuring a high conceptual framework that blends noir schematics with gothic horror dramatics, My Name Is Julia Ross is a tight, fun ride that only takes up 65 minutes o your time. A story of mistaken identity by way of subjugation that through a sensationalist conception, and tight narrative structure, enunciates its underlying themes related to patriarchy and power. One of the more lucid works on the oppression of feminine identity by way of high conception horror/thriller, in which a young, unemployed woman in need of a job finds herself coerced and her identity nearly erased by a man whose privilege is defined by wealth and gender.

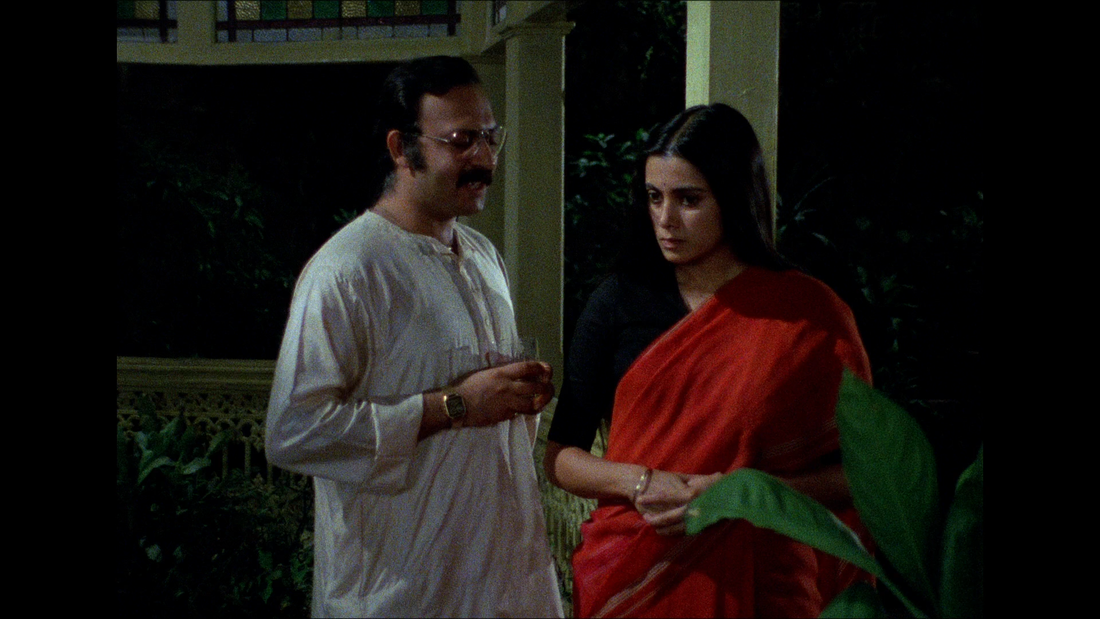

A polemic affront to intellectual hubris devoid of direct action, Govind Nihalani's Party is an astute examination of the relationship between action and observation, detailing the fragmentation and disruption of socio-political ideology when placed in contention with one's own economic prosperity. Taking place over the course of one evening at a dinner party, where the ruling class of India has come to celebrate a literary award bestowed to one of India's most cherished writers, Party is a meticulously layered ensemble piece that slowly unravels and contextualizes its characters with grace and conviction, detailing the corrosive effect wealth can have on social prosperity while ruminating on the meaning and purpose of art itself. Over the course of the evening performative pleasantries erode and competition and judgement seep out, revealing how even among individuals of the same status ego often supplants altruism - the pursuit of elevated social status and the potential for more social capital, and by proxy material wealth accrual, breeds competition which distracts and distorts larger societal progress. Through the film's intricate exploration of the ruling class, Party demonstrates the corrosive toll which this privilege and prosperity can have when not properly checked from within. Hubris manifests through those whose affirmation of worth is tied directly to their own social status. Their means of cognitive exit are through guilt or dissonance, when stood up against the larger societal struggle for equality and justice. In this fashion, Class itself can often create a divide between the individual and the collective, the art transcends such divisions while the artist themselves often falls victim to the allure of hubris and a heightened sense of worth. While some look at an unjust world and demand change, others merely accept their conditions, profiting off the inequalities of the polity to enrich themselves. For Govind Nihalani, this is a passive & toxic act of political activism, nothing more than a performative romanticization of injustice for those who don't directly commit their time and labor to the struggle. For the cultural elite who expound virtue without action, is their intent genuine, or merely rooted in personal elevation across social capital and economic gain? Managing to be intellectually rigorous while also emotionally poignant in the way it skillfully extrapolates the ethos of its assorted characters, Govind Nihalani's Party is a pointed, persuasive attempt to elucidate the concept of art in a way in which it is tied directly to social obligation, inciting the idea that words without action are intrinsically egotistic in a market society

A charming albeit dated comedy that takes on a different meaning when contextualized against the historiographic of the urban-suburban divide in post-1960's America. Adventures in Babysitting frames the city as a terrifying entity, a bastion of depravity and filth once the sun goes down, which is a foreign spatial environment for suburban white kids. While troublesome early on in its depiction of both class and race, Adventures in Babysitting is ultimately a film of good intentions, with its denouement rooted in the notion that one cannot be judged by appearances but instead by their character as autonomous individuals. A nocturnal adventure comedy that plays into the fears of white middle-class diaspora from urban areas, Adventures in Babysitting could be an interesting double-feature with a film like Judgement Night. They both take advantage of the dichotomy between urban and suburban life in which the city itself is portrayed as a vessel of crime, violence, and poverty, which is inescapable once the sun goes down. A fun, family comedy that takes on a different context as an adult, specifically now that one is removed from the specificity of the epoch in which it was produced.

One of the better personifications of just how damn infectious Burt Reynolds could be as an actor. Starts as a charming the-good-old-boys flick before divulging into an effective meditation on mortality. The disparity between talent vs labor in the eyes of the studio system takes on an interesting subtext here, but it is far from fully formed. Hooper at its most transparent is a sly and effective ode to stunt work, exhibiting the Stunt Man as heterodox force in industrial filmmaking, a maverick of their time who largely operates outside of the social and professional expectations of the Hollywood studio system. Essential to the Hollywood apparatus yet often viewed as expendable, the characters of this film exhibit this ethos, at times standing in defiance of mortality. The film exudes some serious 'the good old boys' energy, and the finale is absolutely an incredible display of practical stunt work, the carnage on display dazzles while also inviting a lens of self reflexivity - a story about stunt men pushing themselves to the limit which features some of the most deft-defying stunts in its finale ever committed to celluloid

When movies still meant something both in terms of cultural allure and the fantasy fulfillment they provide, Richard Rush's The Stunt Man is a dazzling work of late-era new Hollywood, being both an ode to the craft and artistry of stuntwork while also managing to be a subversive albeit playful examination of hierarchal-industrial filmmaking and the combative relationship between artistry and commerce. The toxic relationship between egomaniacal director - played to perfection by Peter O'Toole - and his stunt man - an aimless Vietnam vet who is cast in the film out of desperation - provides ample opportunities for a thematic investigation related to Hollywood as a whole, yet it also could be interpreted as a larger investigation of into the state of the American polity itself, one in which capital is often resting above labor on the hierarchy of perceived progress due to the embracement of laissez-faire ideology. Sure, The Stunt Man could be simply viewed as an investigation into egomania yet the lack of autonomy the film showcases across its characterizations suggests otherwise. Cameron, a newcomer to the screen, is manipulated ad nauseam but other actors - namely the actress and ex-lover of Peter O'Toole's director character - are also coerced. The actions of O'Toole characterization themselves are arguably influenced for the worse by the restraints of commercial filmmaking which demands short-term results over long-term craftsmanship - he is simply a cog himself in the machinery of industrial filmmaking. Cameron, the Vietnam vet turned stuntman, has been a cog in the machine that is American imperialism, and while the stunt work at first offers him economic rewards, it becomes apparent his body itself has just been re-contextualized to another powerful apparatus of America, a utility for the interests of others - in this case, the Hollywood machine. Richard Rush's direction here really stands out, the camera's gaze manipulating the viewer at nearly every turn, the audience is caught between artifice and naturalism much like Cameron, unsure what is real and what is manufactured movie magic. The apparatus of government and Hollywood are juxtaposed thematically, elucidating the opportunism intrinsic to those who wield the power of such institutions. There is little autonomy for the artist or individual against such power structures. The visualization of Peter O'Toole descending from the heavens in his on-set crane like a goddamn deity forever and always.

Life is difficult, love makes it ultimately meaningful. The desire to quantify, interpret, compare, and contrast every experience through one's own epistemological lens is foolish, given the intangible nature of objective truth in a world of perception. Happiness is forged from within. Ryosuke Hashiguchi continues to astound me with his deeply affectual gaze. Earnest about the weight of existence, his characters are multifaceted vessels for his astute exploration of the human condition and the various modes in which people search for a sense of self. With All Around Us, the coercive effects of internalized pain are saliently expressed through the rocky but undeniably loving relationship between two individuals who consistently struggle to express their underlying emotions. The ability to let go of self-doubt is paramount for any meaningful pursuit of happiness, with the trials and tribulations of these two characters being largely constructed out of false pretenses such as emotional insecurities and at times, a lack of emotional intelligence, which distract them from their underlying love they share for one and other. A film which doesn't deny the difficulties of life while recognizing that the shared nature of existence is ultimately what makes it all worth it.

|

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed