|

The conception of a community purveyed through the rebellious and impressionable eyes of a child, When I Saw You is a tender, reserved portrait of diaspora. An environment ripe for indoctrination, one in which the line between introspection and action is constantly prodded, the emotional fulcrum of this story sits between a mother and her son, the weight of the world and its vast and varied ideas about liberation weighing on the maternal oath of a mother whose tasked with fostering her impressionable son in a time of such volatility. Imbued with innocence, yet embedded with a sense of injustice and frustration, When I Saw You is a quiet humanistic portrait of mothers and sons, identity, and the social tenets which form the construct of home.

0 Comments

Pure unadulterated cinema, a singular evocation of the hollow veneer of opulence expressed through narrative abstraction in which its rhythms and modules of discovery are unequivocally cinematic. Largely devoid of literary or stage sources of influence on its narrative language, India Song employs a sensual lens to detail the vicissitudes of despondency. Extravagance and power devoid of spiritual fulfillment - the aesthetic built around emptiness in which the material indulgences of ambassador's vast estate evoke the underlying emotional destitution.

A conceptually pointed commentary on the unjust and oppressive treatment of sex workers in post war Japan in the late 1950s, Girls of the Dark is a humanistic portrait of rehabilitation and autonomy, providing an incisive critique of the cold, blunt instrument of legalism when predicated on reactionary moralism. A well-crafted narrative which details the trials and tribulations of a Kumiko, a former sex-worker who is in state-sanctioned rehabilitation, Girls of the Dark provides an honest depiction of the complexities of such issues of morality. Astute in its ability to separate the political and moral claims from the personal/social ones, Girls of Dark is a story about autonomy and self-love, detailing through its character arch an individual who has lived a life of servitude, her actions either being implicitly dictated by the male gaze or explicitly by the crude mechanism of compulsory legalism. Remarkably veering clear of didactic thematics, Girls of the Dark is a poignant study of one woman's struggle to love herself, suggesting that any meaningful reform must be ignited from within, initiated by love and kindness not forceful notions of shame, pity or morality

Essentially The Bad Seed served up with Nobuhiiko Obayashi's formalist panache and a dash of delirium in which the evil child trope is traversed with such an assured sense of direction and manic energy that it is hard not to admire. The moral conundrum and disbelief related to whether a child is even capable of such acts of violence is a device in which Obayashi unabashingly provokes and prods, invoking the supernatural and metaphysical elements throughout his narrative construction. In its finale denouement, the film winds up feeling singular, despite its familiarity, showing an underlying sense of intellectual clarity beneath the film's absurdest veneer

Conceptually ambitious and structurally singular, One Cut of the Dead is a remarkably creative endeavor which employs the zombie film subgenre to deliver a genuinely endearing, funny, and low-key incisive look at performance and the facile components of creation. Farcical in moments yet coming completely from a place of love and respect for the creative process and filmmaking in general, One Cut of the Dead explores the complex nature of truth imbued in any work of art. Having great affection for the process of filmmaking, particularly during production,One Cut of the Dead exhibits an infectious playful temperament which is hard to resist.

An intricate examination of sisterhood which takes a pensive look at the complexities and labyrinths which sculpt and shape identity, Margarethe von Trotta's Marianne and Juliane traverses the socio-political fulcrum which sits between reform and revolution to deliver an intriguing tale of the tumultuous but ultimately committed relationship between two sisters. Oscillating between past and present, Margarethe von Trotta's film examines the divergent paths which persist in even a shared social environment such as sisterhood, exhibiting how convictions and beliefs calcify and influence actions. Resolute in the belief that the persistence of love in the face of such divergence or differentiation is a necessity, Marianne and Juliane is incisive in its recognition that in the face of conflicting sensibilities, respect and humanism is what ultimate drives a collective sense of understanding. Managing to holistically view the personal, political, and social as interdependent forces, Marianne and Julianne is a humanistic portrait of sisterhood first and foremost, using this intrinsic bond to deliver a mature and subversive examination of identity, social action, and vicissitudes which persist in any meaningful pursuit of progress.

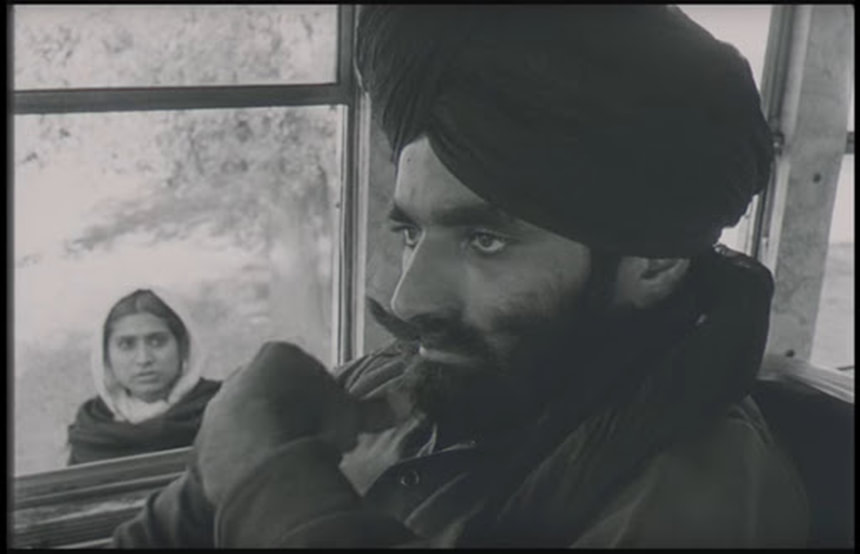

Extremely Bressonian in its formalist sensibilities, Uski Roti employs stripped-down performances which subtly express the underlying vitality of its subjects through a careful and calculated lens in which the smallest moments reveal the unseen omnipresence of oppression. With Uski Roti the story itself is simple yet poignant, the plotting is thin yet efficient, showing a pointed clarity through a conceptional framework which focuses on social environment, invoking the spatial and temporal environment of its characters - the rhythms, redundancies, and repressions which encapsulate the day-to-day life of these woman who live in servitude. Featuring very little dialogue, Uski Roti relies rightfully so on movement, staging, and performance to convey its cultural critique. The struggle is largely internal-facing, it's alluded to, never spoken explicitly, the sense of fear being a foreboding and palatable throughout the film, revealed through subtle glances, touches, and postures. The sense of touch is a empathetic device for these woman, an implicit way of expressing their shared state of affairs without outright agitation; Their faces often a vessel of deception which conceals the their true emotions. These actions are defensive mechanisms, learned and normalized over-time by these woman who survive in an environment in which they are clearly viewed as inferior or secondary in their status in society. The arduous journey for woman is commonplace, normalized in uber patriarchal culture.

With Eliza Hittman's latest film revolving around such a hot-button issue as abortion, the film is remarkably graceful, never divulging into polemics or melodrama, focusing much more on the humanist element than any type of political diatribe. Evoking such a sense of intimacy through its formalist sensibilities in which the close-up is used with tactical precision, Never Rarely Sometimes Always has a pensive temperament, one with conviction but also self-aware enough to recognize the social and emotional complexities of such a transformative event. Institutional failure and the geographical-based inequalities of care are encapsulated with resolve and yet the ambiguity of the story centered around the "inciting incident" is a masterful tactic which really helps this film reach its potential. Strengthening the film's intent and ambitions through showing an unwillingness to define all the terms of its story, Never Rarely Sometimes Always manages to be expansive and substantive in its depiction of female autonomy and their secondary status in a patriarchal society. High-end drama is cheap and frankly vulgar when detailing such an issue and Hittman's film refuses such moments, recognizing that it's often in the subtleties of social interaction- the small moments which are excused as common place- where the oppression of the status quo prevails. Detailing a hotly contest issue with intimacy, Eliza Hittman's latest work exhibits moral and thematic clarity through a simple, efficient narrative which feels deeply expansive when it comes to detailing one of the ongoing political debates of our time.

The striking and varied landscapes and cityscapes of China provide an ample aesthetic backdrop for Peng Sanyuan's Lost and Love, a story which exhibits proclivities towards a saccharine story and sentimentality while it provides ruminations on loss, grief, and the paternal bond between father and son. Providing insight to an aspect of reality in modern day China I myself was unfamiliar with - prevalence of child trafficking - the emotional fulcrum of the story is centered around the relationship which evolves between a persistent father looking for his lost son and a young, bike mechanic he meets along his journey, who himself was a victim of child trafficking. Coming from different perspective of the same experience inevitably provides mutual aid to both of their damaged psyches; the evolving bond they share grapples with grief, loss, identity as they find a semblance of fulfillment in each other. The labyrinths of memory, the deceitful aspects it can place on an individual dealing with a crude cocktail of desperation and hope, are exhibited through this relationship, and in Lost and Love best moments, ones which don't aim for cheap payoffs, the film offers incisive commentary on the powerful effect love can have on our ontological fortitude, though by-and-large, the film's narrative proclivities are rooted in saccharine notions of a satisfactory conclusion.

Invoking the neo-realist classics with its aesthetic sensibilities and narrative designs, Nothing But A Man is a harrowing achievement of American cinema, a persuasive and detailed testament to the African American experience in the 1960s American South. Uninterested in melodrama or any true inclinations towards moral claims of right and wrong when it comes to the imperfect characters which it portrays, Nothing But A Man feels more like an experience, one which is piercing in its pure and unadulterated depiction of tough existence of growing up black in a time when equal opportunity was merely aspirational and the only way to live in some semblance of peace was to live it in subservience. Void of sentimentality or any form of emotional conscription, Nothing But A Man encapsulates, through its cinematic rhythm, how rage is simply commonplace, a reactionary device used by our good-natured but flawed protagonist whose been molded by the harsh realities of the world around him in which repression is the norm and servitude the expectation. The mental and physical deterioration such harsh conditions invoke on those who are forced to live in them is fully realized through the film's patriarchal relationship, one in which our young protagonist's father - a man whose temperament is mix of unpleasantry at best, and downright nastiness at worst - transforms over the film's running time into a character who warrants the viewers' sympathy. This man's punch-drunk demeanor serves as warning to our protagonist, a window into the future, the potentially destructive outcome for a young man whose only crime is wanting personal autonomy. Nothing But A Man is a beautifully told narrative that strikes all the right emotive chords throughout its love story between two individuals and their struggles, our female and male protagonists each being erected differently by the racial oppression and social realities of their surroundings.

|

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed