Josh, a documentary filmmaker, and his wife Cornelia are a middle-aged couple living in New York. While Josh struggles to finish his latest documentary, one he's been working on for the better part of a decade, Cornelia finds herself constantly pressured to have a baby from her group of friends, all of which have kids. When Josh and Cornelia meet Jaime and Darby, an exuberant young couple, they find a new sense of liberation from middle aged life. Noah Baumbach's While We're Young is a nuanced study of middle adged stagnancy, exposing the fears that exist when comparing oneself to the society's expectations. That is at least what the film begins as, but what makes While We're Young one of Baumbach's most fascinating films is its layered narrative that touches on a host of interesting ideals about modern society. Touching on societal expectations, our growing attachment to technology, and filmmaking questions centered around colloboration and the fine line between fact and fiction, While We're Young is a film that is overstuffed with ideas, some of which are certainly more developed than others. Using these two couples, one in their 20s and one in their 40s, Baumbach captures the contrast of these age groups, showing how young people are eager to conquer the world, while as one gets older it becomes more about what u have and finding happiness in those things. Ben Stiller's Josh character is the main force of this story, a man whose struggling to accept where he is as as filmmaker. Jaime offers the reverse to this, a young man who is just starting out, attempting to make something for himself. As the film progresses, it becomes apparent that they are more alike than they care to admit, just living at differ points on the same timeline. By contrasting these two characters, While We're Young isn't just a film about the midlife crisis, but a larger film about society itself and how it defines age. While some of the film's ideas are more mentioned than explored, Baumbach's film shows much more empathy for Jaime than I could, but that is what makes While We're Young feel like Baumbach's most mature feature yet.

0 Comments

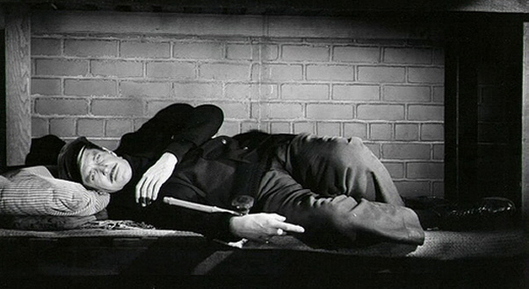

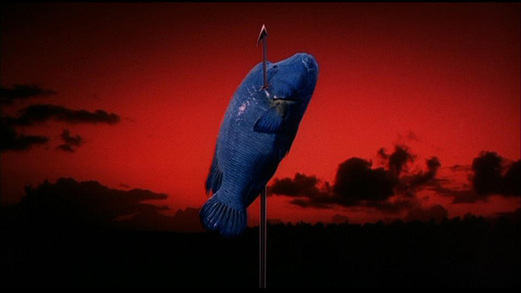

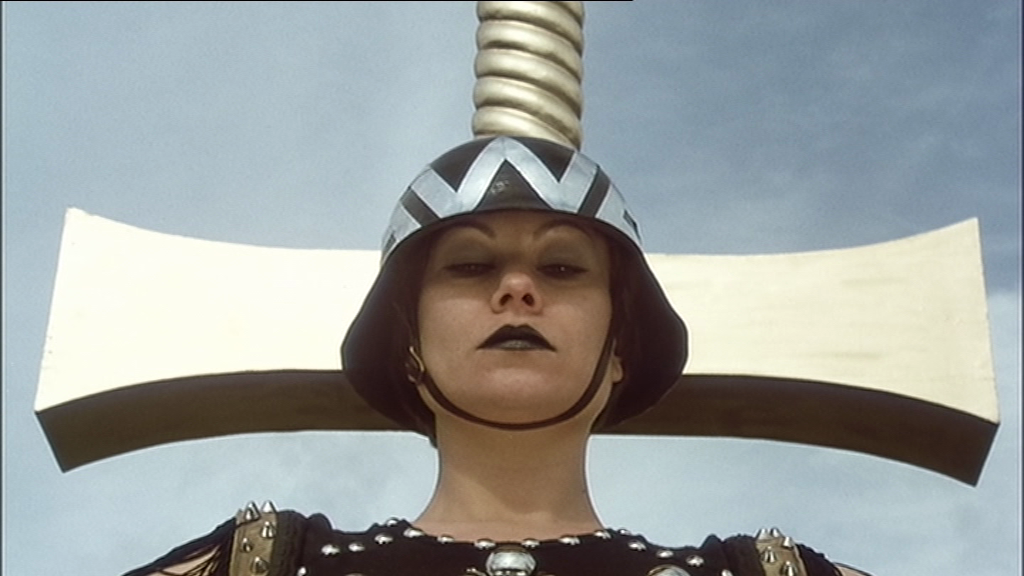

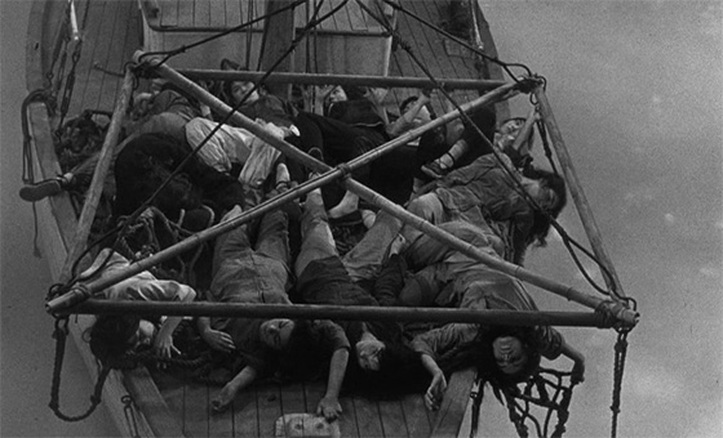

If you are a fan of ridiculously bad movies that do pretty much everything at an arbitrary level, then Edward D. Murphy's Kung Fu Cannibals is a film you probably will enjoy. The film has zombies, cannibalistic monks, female slavery, a Hitler wannabe, Gay henchmen and a gratuitous amount of nudity. Oh, and the acting from pretty much top to bottom is atrociously bad from start to finish. Kung Fu Cannibals is essentially a mix of sleaze and action sequences that are loosely strung together by a ridiculous narrative, so basically what you'd expect from any film called Kung Fu Cannibals. While I enjoyed it for what it was, in particular the unintentional funny dialogue and ridiculous stunts, Kung Fu Cannibals left me expecting more, given the title alone, with the film never quite going as over-the-top as I was hoping. For example, there needed to be more Cannibalism and action, as the film tended to drag, a really bad sign for a film of this ilk. It's entirely possible that these type of films just don't do it for me the way they used to, and I wasn't inebriated, but I never found this film to be the same level of absurdest, bad-movie fun as other favorites like Ricky-Oh and Miami Connection.  After serving three years in prison, Enrique returns home to the Bronx to discover his life as he knows it has changed drastically. His wife, Angela, struggles with her feelings, torn between her old husband and a new man she recently met. Enrique's teenage son, Michael, represents an even larger concern for Enrique, as this young man struggles with his sexuality, routinely dressing up as a woman, the only way Michael feels comfortable in his own skin. Coming from a tough, criminal lifestyle, Enrique struggles to grasp and understand his son's sexuality, clinging to his own masculine ideals of what a man should be. Rashaad Ernesto Green's Gun Hill Road presents an effective portrait of a family turn apart by incarceration, being a powerful study of a young man attempting to discover himself in an environment that defines a man's worth by very primitive ideals centered around masculinity. Gun Hill Road works best in its sensitive depiction of Michael's struggle, relaying the day-to-day aspects of a young man attempting to find himself. His father Enrique is a man who simply cannot fathom his son being a homosexual, being a man whose urban ideals of masculinity are defined by toughness. Using this broken family unit, Gun Hill Road paints an effective portrait of the struggle of re-assimilation that many convicts have back into society, though the film does come off a little "after-school special" at times. My biggest critique of Gun Hill Road would that it's simply too over-stuffed with melodrama. From the mother's emotional struggle to decide between her old and new relation, Michael's struggle with his sexuality, and Enrique's struggle with becoming a father figure, Gun Hill Road could have benefited from a little less drama. I wish the film would have not bothered with the mother's love triangle, as it doesn't add much, just taking away from the film's ability to offer a more pensive study of the disgusting viewpoint that this urban lifestyle has on homosexuality. With a few extremely powerful and poignant sequences, with the prostitution scene being a high point, Gun Hill Road is a solid independent film exploring a broken family unit, that could have certainly benefited form a more streamlined narrative.  Ken Russell's Mahler takes place on a single train ride between Gustav Mahler and his wife, Alma, as they confront the reasons for their faltering marriage and love for one and other. Besides this shell of a structure, Russell opts to through all narrative out the window, focusing on Mahler's emotions and feelings which lead him to where he is. Through a ton of flashbacks, some very surreal, we see how Mahler's past has shaped his present. I really like this idea of Mahler's personal life being in turmoil because of his art. The film shows us how he sacrifices everything- His marriage, his children, his religion for the sake of his music. There are so many memorable scenes from Mahler's interpretation of his death, capturing all the insecurities and pessimism, to the sequence where Mahler embraces Catholicism, which was just hilarious and fun. Russell's disdain for Catholicism is in full effect during that sequence. Pretty much every frame, every composition, has a purpose in showing us something about Mahler's life. The scene where he witnesses his father cheating on his mother is a perfect example of Russell's heavy use of symbolism- the pitch fork laying perfectly on the center of the young boy's forehead, the image piercing deep into a young Mahler's mind. From an emotional standpoint, I found sequences to be incredibly effective, particularly the small scene about the death of his daughter. I found this film to be more focused and less zany than films like Lisztomania and Tommy, and while I like those films a lot too, this one reached me far more on an emotional level. Thinking about it, this could very well be my favorite film of Ken Russells which I have seen.  Taking place in Switzerland in the near future, Raoul Ruiz's That Day opens on LIvia, a young woman sitting near the roadside of a field, nestled under a tree. Livia is mentally ill and after interacting with a group of prognosticators, she is expecting the following day to be the most important day of her life. Livia's delusional vision couldn't be further from the truth, as her step father schemes to have Livia killed, intent on inheriting the business empire that currently resides under Livia's name. Concoting a devious plan, the father releases Pointpoirot, a murderous mental patient from the asylum, leading him directly to the house where LIvia is all by herself. Unfortunately for the father, Pointpoirot and Livia have a lot in common due to their mental issues and delusional visions from above. Raoul Ruiz's That Day is a bizarre and absurd black comedy that offers a unique mediatation on death, money and false spirtuality that is strangely Ruiz's most accessible film. That isn't exactly saying too much about That Day's accessibility, but the absurd, playful tone makes the film better off in that regard than most of his other work. The film jumps between clever and subtle humor regarding most of the other characters, but the relaionship between Livia and Pointpoirot that unfolds is absurdist madness at its finest. Pointpoirot and LIvia become infauated with one and other but every once and awhile Pointpoirot becomes crazed, attempting to kill Livia, needing to slaughter someone to fulfil his needs. With Livia being her own brand of crazy the two are able to look past their faults, forming one of the most absurd and strange love stories commited to celluloid. Their performances arent over the top, almost subdued, but how Ruiz captures their false spirtuality is compelling and layered. Ruiz's film features people who are all driven by something, with the family driven by greed and our romantic couple by false idols. While not as visually striking as much of Ruiz's work, That Day is a beautifully orchestrated film where his style is very prevalent throughout. Ruiz's signature use of foreground and background in compositions is on display as much as ever, and the camera movements were very impressive as well. Being a playful, absurdist comedy the filmmaker doesn't seem very interested in inserting his ideals, rather presenting a strange story of the insanity of humankind.  Albert Zugsmith's Confessions of an Opium Eater focuses on the slave trade of young Chinese woman in turn of the century San Francisco. We follow a philosophical bantering adventurer (Vincent Price) as he descends into this underground world of trap doors, secret rooms, hidden passages, and lots and lots of opium. It's essentially an early 1930s adventure film meets drug movie, that presents an original and fascinating look into the Chinese slave trade. Vince Price is awesome, per usual, as the adventurer who spews out philosophical ramblings like no other, and while most of the time these discussions are endearing and timely, they can come off a little over bearing at times. That being said, this philosophical banter does pay off at the end, with a fantastic closing sequence that wraps the film up nicely. The drug sequence and subsequent chase sequence in the middle of Confessions of an Opium Eater really stands out, being stylistically impressive and revolutionary for the time period. The decision to film the entire chance sequence in slow motion due too our main protagonist being high on opium is a beautiful sight to behold, and really brings the whole sequence to life. The sound design is very bizarre, yet perfect for this Asian themed tale, being another attribute that makes Albert Zugsmith's film a unique experience. As funny as this sounds, Confessions of an Opium Eater reminded me somewhat of Carpenter's Big Trouble In Little China, as it presents this culture clash in San Francisco. I couldn't help but wonder if John Carpenter is a fan of this film, being as it could have easily served as some form of inspiration. Considering the film's off-beat sound design and drug-infused narrative, it's no surprise that Albert Zugsmith's Confessions of an Opium Eater was overlooked during its original release, but given that there is a lot to appreciate, it's no surprise that the film eventually became a cult classic.  Renowned French photographer Antoine D'Agata's first feature-length work, Aka Ana, is a haunting visual essay of prostitution in Tokyo that should absolutely not be experienced by anyone who is easily offended by sexual imagery. Aka Ana is told through the eyes of six distinct voices, each prostitutes who open up their souls to the viewer, as D'Agata juxtaposing visually haunting imagery of these sex workers in their natural habitat, servicing clients and and shooting heroin, anything to escape the world they inhabit. Each woman brings a unique dynamic to Aka Ana. One woman feels empowered by sex and views it as a way of seizing power from the male ego, while another woman towards the end of the woman is emotionally shattered, essentially a souless body soaked in misery. Aka Ana has no agenda outside of showing prostituion for what it is, being a very raw depiction certainly explains its lack of distribution. My favorite aspect of Aka Ana is how it gives off an aura of male oppresion, as these woman unbare their souls against imagery that presents their world and viewpoint of the men, almost symbolic of the nature of the world right now. D'Agata is a documentary filmmaker with strong convictions, not afraid to assault the viewer with his films, pushing the viewer to experience thier limits as he presents an evocative portrait of art and life. Antoine D'Agata's Aka Ana reaches levels of intimacy in its subjects that few documentaries can match, offering a soul-shattering and haunting experience that I'll never forget.  Jean Rollin's Fascination is another intoxicating, dream-like film from the filmmaker that is centered about a thief, who after double-crossing his partners, comes across a mansion where he plans on holding out until nightfall. The mansion has only two occupants, beautiful woman of course, who act very strange, showing no desire for him to leave. This film is quite brilliant in how it gives the viewer absolutely nothing and uses that to it's advantage in creating a sense of impending doom as the clock approaches midnight. The atmosphere of Jean Rollin's films are always impressive, and with Fascination, Rollin has crafted another beautiful film full of imagery that meticulously blends eroticism and sexual violence, juxtaposing characters which inhabit these two ideals. I love how these two women routinely tease the thief pretty much warning him that something bad is going to happen, yet he doesn't concern himself with them, mainly due the fact that he views them as harmless woman, nothing more than a beautiful sight to behold. The sequence with Eva and the Scythe stood out to me and per usual for Jean Rollin the ending leaves the viewer stunned. While Jean Rollin could certainly be classified as a director I have trouble writing about, Rollin's infatuation with the relationship between sex and violence combined with his intoxicating visuals make Fascination another memorable film. Fascination is probably Rollin's most accessible film, but prepare yourself, as this is not a filmmaker interested in spoon-feeding anything to the viewer.  Aniki Murakawa, a long-time member of the Yakuza, has recently been sent to Okinawa by his boss in an effort to help settle a dispute between two rival gangs. Murakawa is a man who has begun to grow tired of his gangster lifestyle, even considering retirement, though he reluctantly accepts the job after being assured of its relative ease. The mission ends up being anything but, as a bloody conflict erupts under somewhat mysterious circumstances forcing Murakawa and his men to retreat to a secluded beach-side home in order to gather information. As time passes it becomes more and more clear that Murakawa was indeed set up by his superiors, in an effort to take control of Murakawa's lucrative territory. Takeshi Kitano's Sonatine is one of the more meditative studies on the Yakuza lifestyle, using Takeshi Kitano's cold gaze to capture the heart-hardening profession that slowly wears its subjects downs. In Sonatine, the Yakuza lifestyle isn't presented in a flashy, exuberant way, as the film instead feels far more focused on the quiet moments of boredom and isolation that make up much more of Yakuza man's lifestyle. Sonatine really captures how Murakawa, an enforcer, is basically the slave to his superiors, unwilling to have his own identity in the criminal underworld, being merely a vessel for the yakuza bosses wishes. When Murakawa and his men arrive on the beach the film takes a idyllic turn, with Murakawa striking up some semblance of a relationship with a local girl who he saves from being sexually assaulted by one of his men. For me, Sonatine is a film about a man inability to capture his own independence and freedom from the Yakuza world. Completely disenchanted from the thrill of violence, Murakawa begins to see the pointless repetition of this lifestyle, with the young local girl offering him some semblance of a normal life. Not to be confused with a redemption story, Sonatine captures a man whose always served a master, with the bloody finale and finale sequence being very symbolic of a Samurai's practice of Harakari.  Carol, a beautiful, young woman, is a damaged soul, desperately seeking the attention of the world around her. She routinely performes eccentric acts in public in an attempt to be noticed, unable to break free of the cold world she feels around her. Her boyfriend doesn't share her same eccentric qualities, being a sensitive, considerate man, who seems to have adjusted well to the social normalities of society. Carol wants him to express his love in some way for her, even attempting to force some display of physical affection. Unable to take the pressure anymore, Carol reports herself as a terrorist to the authorities, seeking some strange form of solace in the asylum. Werner Schroeter's The Day of Idiots is a perplexing and ambiguous piece of filmmaking about a group of deeply damaged woman. The key to trying to understand Schroeter's nightmarish study is not take what occurs literally, understanding that much of The Days of Idiots seems to be told on a symbolic and allegorical level. While a film like this is certainly up to many interpretations, Schroeter seems to using these damaged woman's struggles as a metaphor for the importance of personal needs, desires, and idenity. While in the contruct of the narrative these woman are deeply disturbed, on a surrealist level they appear to represent oppression of the individual, with the mental institution being a symbolic representation of the social standards and norms of society. One could also argue that Schroeter's film is a deeply unconventional story about a woman's quest for love, with Carol being driven mad by her boyfriend's lack of expressing his affection. Even the final sequence, when Carol escapes the mental hospital and is free from the oppressive regime she appears aimless, stillunable to find what she has always been looking for in 'love'. Death comes in the form of a car accident, offering Carol another way out of her suffering. Even if Schroeter's film is merely an outlandish excuse for him to create a haunting portrait of insanity, The Days of the Idiots succeeds with flying colors, being a cinematic barrage of suffering and torment. Possibly Werner Schroeter's most challenging film of all, The Days of the Idiots is a unique cinematic experience that is open to many interpretations. |

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed