|

A bold and brave vision, Urszula Antoniak's Nude Area is an immersive descent into the sensual and seductive relationship which unfolds between two female teenagers over an idyllic summer in Amsterdam. A silent film in which zero dialogue is uttered throughout its 80 minute running time, Antoniak's Nude Area is a film reliant on visual aesthetic and non-dialogue driven performance, deconstructing budding young love in a way that is reflective and honest about the emotional turbulence and internal psychology which takes place in any relationship that is stuck somewhere between elements attributed to love and lust. Nude Area asserts and embraces the ideal that love is not a discernible or definable in logical terms, it's fueled by the messy nature of emotion, examining this young romance through a lens that reveals loneliness, lust, fragility, and seduction - a relationship that feels dangerous due to its unknown nature, yet sensual and sexual due to the this unquenchable, mutual attraction. Objective reality is blurred throughout Nude Area's impressionistic odyssey, as the viewer becomes unsure of what is subjective vs. objective, as the relationship itself becomes defined by the internal emotions and psyches of its main characters, one in which the viewer is simply an outsider, at the whims of what is granted to us by these two leads. Unwilling to unfold in conventional terms, Nude Area rejects narrative storytelling for an impressionistic/atmospheric lens, a film that gracefully and profoundly examines attraction and desire through the head space of two young woman, doing so with honesty as it juxtaposes the more dangerous aspects related to unbridled carnal desire with potential goal of finding something more, something geniune and selfless in love & companionship.

0 Comments

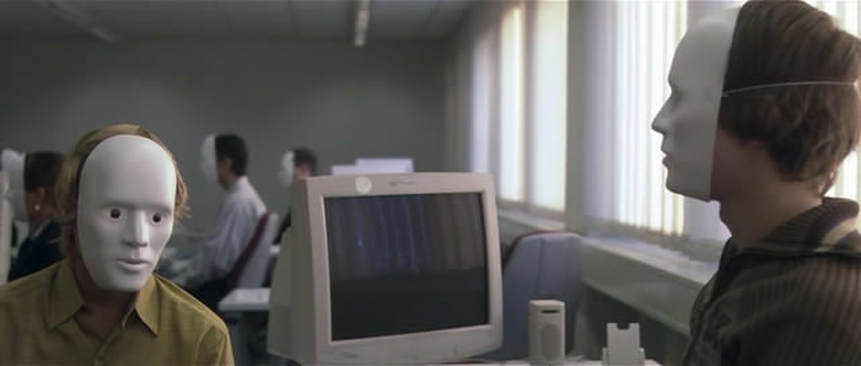

Christoph Hochhäusler's I Am Guilty is a pensive study of emotional detachment, alienation, and existential malaise, a film that gracefully deconstructs the cold, dehumanizing effect which the passage into adulthood can have on the adolescent, one in which the individual comes face-to-face with the objective reality of life itself- no one is special in the realm of space and time. Focused on Armin Steeb, a young man on the brink of adulthood whose just finished school but clueless and perhaps directionless when it comes to seeking out a career, I Am Guilty exhibits in its main protagonist a character whom is painstakingly adrift, confronted with the realization that what happens next in life is up to him and the world as a whole is relatively ambivalent. In between haphazard job interviews and his pining for a local girl's affection, Armin finds himself growing increasingly infatuated with a fatal local road accident, even claiming responsibility for it via an anonymous letter to the local newspaper, anything which makes Armin feel some type of notoriety, significance, or power. I Am Guilty isn't merely fixated on exhibiting depression or longing but more the general effect which detachment and insignificance can have on the psyche, showcasing in Armin a character whose become awoken to the abject meaninglessness of contemporary society, one in which personal ambition is often trampled by the will of the masses. A child who has had a privileged life up to this point, Armin is a character struggling to find his identity and purpose. Like most people his age, he internally labors to comprehend what he wants to do with his life, with every passing interview only reinforcing his fractured psyche, one full of frustrations and fears related to his inability, or perhaps unwillingness, to commit to something definitively at this point in his life. I Am Guilty strikes a great balance in its deconstruction of its main protagonist, managing to relate to and find empathy for Armin's struggles while not placing Armin completely void of some of the blame for his general detachment and malaise, understanding that these failures are placed on the feet of both the individual and society. Armin's detachment is influenced by fear of responsibility and lack-of-control about what the future holds, yet it's his desire to feel significant again, reclaim some form of power, that drives the film to its ominous conclusion. Philosophically transfixing in its assertions related to detachment, existential nature, power/authority, and worth, Christoph Hochhäusler's I Am Guilty is a unique character study that is balanced in its ability to be critical of both the individual's choices, while simultaneously showcasing the dehumanizing nature of modern society.

An astute, impressionistic debut, Kevin Phillips' Super Dark Times' is harrowing descent into the shattering of innocence, deconstructing the perverse and subversive effect which trauma and violence can inflict on the psychology of impressionable young minds. The story of teenagers Zach and Josh, best friends whom commit a gruesome accident only to cover it-up, Super Dark Times details the erosion of childhood naivety and the escalation of guilt-ridden paranoia, showcasing how two close friends see their relationship distorted- mangled under the weight of this damning secret which potentially holds their future livelihoods in the balance. The childhood characterizations, the friendships themselves and how these character's interact sting of authenticity in the opening minutes, with Super Dark Times' cinematography imploring a cinema verite style, one which gives these characters a lived-in, authentic feel, a looser, care-free framing of these characters which is effectively shattered by the gruesome accident. After this accident, the aesthetic changes, as Super Dark Times becomes more surgical by design, intricate and immersive in its ability to create an ominous, dread-soaked atmosphere, one which exudes paranoia and tautness in every frame, transporting the viewer into the impressionable young mind of its main character, Zach, a teenage boy who grows more and more concerned about the psychological effect such an incident is having on his friend Josh. Unfortunately, Super Dark Times' polished, stylish veneer cannot distract from the narrative's inability to earn its ending, as the film's intentions to capture the toxic, alluring nature of violence falls heavily flat, due in large part to Josh's characterization being poorly explored by comparison to Zach. Josh's story arch, one which sees this character effectively lose his moral compass, doesn't completely work in the context of the story, as it becomes a tad heavy-handed and far-fetched to see him end up in the situation he finds himself in. Super Dark Times seems to want to show the perpetual state of such violence, the alluring nature it can have on those impressionable enough to become entranced with it, yet the film never spends enough time grappling with Josh's torn psyche, relying too heavily on Zach's internal conflict to serve as a surrogate to Josh's experience, something that doesn't exactly work given the nihilistic ending. A psychological horror film which impresses due to its keen eye and impressionistic atmosphere, Super Dark Times is an impressive debut feature which leaves you wanting more from the talented first-time filmmaker Kevin Phillips.

Set in feudal Japan, Kinuyo Tanaka's Love under the Crucifix transverses the forbidden love archetype through the lens of feminism, delivering a powerful and tragic story of individual liberty, love, and choice under the oppressive forces of the time period, where woman were ornamental in nature, prizes for men whom have reached a certain status or power in society. The story of Ogin, the daughter of a tea master, who falls in love with Ukon, a feudal prince, who happens to be a married Christian man, Love under the Crucifix's narrative thrust follows this perilous relationship, one that faces barriers not only due to puritanical decrees related to marriage, but governmental oppression taking place after the Shogun bans Christianity entirely from the region. While the story is centered around this forbidden love, Love under the Crucifix is first and foremost a story of one woman's struggle for empowerment, following a character in Ogin who pins for the ability to have power over her own agency, a character whose female form has left her at a major disadvantage in life, one that leaves her with no liberty or freedom to carve her own path. Ogin is a character who is longing for this love she cannot have, and throughout much of the film's running time she is in a state of isolation emotionally, unsure of where Ukon's emotions are placed while lacking the agency as a female to find out for herself. By the finale of Love under the Crucifix it becomes apparent that Ogin's only sense of empowerment will come in death, as the state omnipresent, coercive nature has her reveal this hidden love against her will in an attempt to grow its power and authority. Ogin as a character comes to realize that in death she will have been granted choice, with this extreme act being one of empowerment, as she is unwilling to be ornamental, only interested in being free to choose to devote her soul to the man she loves, free from the power structures which force her femininity into specific, authority-approved spaces. A tragic love story swelling with femininity and humanism, Love under the Crucifix is a compelling film which bravely and effectively finds the honor in death, asserting that dying proudly on one's own terms, under certain circumstances, can be just as honorable as living.

Ziad Douerir's The Insult is relatively accessible, artistically accomplished, and philosophically profound, a film which is bristling with humanism as it deconstructs the coercive nature which ideology and collectivism can have on general human empathy and kindness. A story of a small dispute between a Palestine refugee and Christian Lebanese man in living in Beirut, Douerir's The Insult is a film of escalation, chronicling how a civil dispute quickly becomes the political ire of a nation, stroking the tensions in Beirut between religious theologies and political ideologies, each which view the outcome of this trial as paramount for the progress of their cause. A scathing commentary on the parasitical nature which larger society can place on the individual, The Insult showcases how these two men find their small dispute amplified and exploited by the various power structures and authorities of society, with the media, various political organizations, and day-to-day citizens effectively using this relatively simple civil dispute as a surrogate to exacerbate the conflicts and tensions which exist in modern day Beirut. These forces only corrupt the situation more, elevate danger and the potential of violence, with The Insult capturing the deterioration of morality and general empathy as the ideological positions begin to grab hold and use a dispute between two men to elevate their respective causes. The Insult asserts that political ideologies can be coercive to human empathy, detailing how violence justified through ideology is almost always perpetual in nature, using this story of a dispute between two men from different backgrounds as a plea for more humanism, empathy and understanding between political factions, theologies, and other tribalism which humanity is so susceptible to adopt. The ending perfectly illustrates this film's largest thematic plea, as The Insult's conclusion slights the larger factions of society that wish to exploit these men's dispute to gain more power or authority. These large factions get nothing, yet these two individual men gain so much, each coming to a point of understanding and general empathy for the other, each understanding that their own personal plight filled with horror and past trauma is not singular or unique but shared, each of which being victims of brutal tribalism that left them emotionally scared and impacted personally.

A socio-political satire and biting allegory about the contemporary state of the European Union, Neil Beloufa's Occidental is ripe with political, racial, and sexual tension, as it uses its single-setting to deliver an astute and balanced deconstruction of life in France under the European Union. Filmed in an aesthetic which harkens back to 70s Fassbinder, with its muted colors and hazy ambiance, Occidental's single location setting feels artificial by-design, a stage which represents France itself through the physical means allotted to the filmmakers, with each character being a symbolic representation of the various schisms taking place in modern European society. The staging and use of mise-en-scene is intricate in design yet simple in presentation, with Beloufa's camera being a dynamic presence in this confined space, serving as surrogate to the viewer for the director, a noticeable presence yet one that only lets us see what it wants us to see, taking the viewer along its basic narrative which lives to serve its larger allegory. From the manager's omnipresent fears and absurd paranoia centered around the "strangers" or "Italians" which arrive at the hotel, to the arch-typical blonde bimbo whose dangerous naivety provides the perfect juxtaposition to her boss, Beloufa's Occidental paints an elaborate yet grounded tapestry of the tensions taking place in the European union, and the various collective forces, each fighting for their perceived share of the what they believe is allotted to them by the nation state. Darkly funny throughout its brisk 70 minute running time, Occidental's treatment of various nationalities - the British, the Italians, etc. is blunt, simplistic, and senseless, as the film intentionally or not makes profound statements about nationalities and how they do nothing more than collectivize people as individuals by something as trivial as their origins or place of birth. The film's treatment, one wrapped in absurdity, danger, paranoia, and confusion from all those involved, pronounces the absurdity of contemporary society fueled by fear of the unknown, being a film which often avoids making assertive political statements about the government structures or current state of the EU, but instead one that focuses on the need for change in some capacity.

A gothic romance masquerading as an elegant period drama, Paul Thomas Anderson's Phantom Thread is an intricate and odd examination of lonely, egocentric characters, each of which grapples over power and control in their shared relationship. Centered around renowned dressmaker Reynolds Woodcock, Phantom Thread establishes its main character as meticulously detailed and in control of his environment, a man who has seen his personal ambitions lead to destruction in his pursuit of any shared human experience, mainly in this case love. Woodcock's relationships, the companionship which it provides only serve egocentric purposes to this man, a character who draws inspiration between various muses until they wear him down with their audacity to want something in return. Meeting his match with the strong-willed Alma, Woodcock finds his control and power disrupted by his inability to shed Alma, as the forces of love grab onto this driven man. Alma, a character who doesn't exactly fit in to Woodcock's world of extravagance finds her own control tested at every turn, a character who grows more and more desperate to seize some power in their shared relationship, unwilling to accept Woodshock's companionship as she wants to be admired and appreciated by Woodcock as much, if not more, than appreciates his craft. Placing more blame on one character or the other in this turbulent relationship is far from the point of Anderson's Phantom Thread, as what Anderson has accomplished with this film is a piercing and honest deconstruction of love, showcasing through these two lonely characters how they find a bit of solace in their shared alienation, each grappling to feel appreciated by the other in the space in which they care most deeply about. Woodcock is in constant pursuit of perfection and appeasing the family business, while Alma simply wants time alone with her husband void of any distractions besides their shared love. While these things at first may seem completely different they are both the things which each other values most, yet through much of the story neither of these characters show much willingness to accept their partner's wishes outright, which leads to escalation and strife Phantom Thread touches on the personal sacrifices related to companionship any driven artist makes, yet its main commentary relates to the push-and-pull of love, acknowledging the hard work and sacrifice that takes place while showcasing how it's in the shared movements which people find happiness and love. While both these characters tend to be self-serving and pine for control of the relationship, their turbulent and sometimes absurdist journey leads them to eventually find solace and some semblance of happiness in each other through their ability to embrace their shared sense of alienation. Paul Thomas Anderson's Phantom Thread is a singular examination of the forces of love and companionship, a ravishing piece of cinema which showcases the malleability of love and companionship itself, despite our attempts as human-beings to define it in some deeply romanticized form.

An ominous, brooding piece of cinema which relies on its palpable sense of dread to drive its ambiguous narrative forward, The Strange Ones is a mystery thriller void of exposition, an academic example of the effectiveness which visual design has on storytelling, especially for a film which chooses to effectively and compellingly eschew formalism. Playful in its disinterest in defining objective vs. subjective reality throughout its running time, The Strange Ones is a film that is divisive due to its unwillingness to provide any concrete answers, forcing the viewer to read between the lines of its characters. The young main protagonist is a character dealing with some internal trauma, and while the film never shows much of a willingness to explain whether it stems directly from pain, grief, or fear, the addled nature of his psyche provides a window into the events of this story that come to fruition in its final moments. Subversive and intricate, The Strange Ones is a film that is hard not to admire due to its bold design and brooding atmosphere, delivering a tense and mysterious experience about a young boy's internal struggles to come to the grips with the darkness that lurks in his past.

Telling the elaborate and engrossing true story centered around the kidnapping of John Paul Getty III's grandson, All The Money In The World is a narratively dense experience which manages to remain coherent, insightful, and compelling from start-to-finish, a testament to Ridley Scott's experience as a filmmaker. Ridley Scott's strongest attributes are on full display for All The Money In The World, which features great economics of filmmaking and a keen visual eye, with the filmmaker tackling the events surrounding this kidnapping in intricate detail while doing so with a confidence that is palpable and rarely seen from such a complex story with so many moving pieces. Overall the script is sharp and assertive, but it often finds itself oscillating between insightful and simplistic from one scene to the next, and while the film should appease anyone looking for a good crime thriller, the story ends up feeling more slight than it should from a thematic perspective. The film's deconstruction of domineering wealth somehow manages to be both nuanced in stretches yet bluntly assertive in other moments, as All The Money In the World's best attribute always seems to fall back more on the characterizations and performances they create. Through this dense narrative, the characterizations and by proxy, performances, shine brightest, and by the end of All The Money In the World all these characters, including the imperious John Paul Getty III, are left scarred emotionally by this horrendous kidnapping.

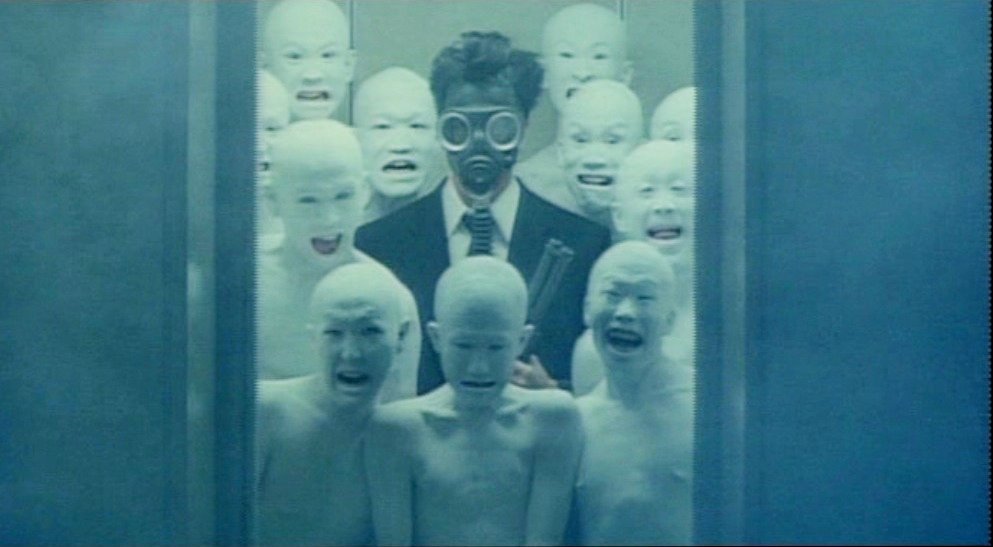

Sabu's Monday is quite the ride- textually surrealist and often absurdist, yet underneath its frantic surface lays a pointed commentary on the binary, simplistic nature of Japanese society. The story of a businessman who wakes up in a posh hotel room, totally clueless about how he got there, Monday chronicles this man's vague recollection of the day before, taking the viewer on a singular experience, one not confined by narrative formalism, where everything and anything seems possible. A social satire and meticulously crafted pitch-black comedy, Monday's message is opaque at first, but throughout its playful exuberance and commanding style the film reveals an assertive take down of Japan's repressed, work-obsessed culture. Throughout this character's journey to recall his wild night, Monday reveals a portrait of Japan that is alcohol-dependent and desperate for cheap thrills, transforming from what feels like a cautionary tale about vices and the self-serving nature and abuse they bring into something more. Many of the cross-sections of Japanese society are showcased throughout Monday, from the Yakuza to the everyday salaryman, and through the main protagonist's odyssey Sabu reveals a film about the complexities of morality and a striking critique of the binary & simplistic examination of good vs. evil. Stylish yet economical in execution, Sabu's Monday is a plee for more kindness in society, using the rapid escalation and perilous situation that its main protagonist finds himself in due to one bad night as an allegory about Japan and the repetitious and perpetual nature of violence created in a society with such binary assertions about right vs. wrong, good vs. evil.

|

AuthorLove of all things cinema brought me here. Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed